Earth has lost as much as 35 percent of its mangrove forests in the past few decades, and scientists predict that these vital ecosystems could all but disappear in the next 100 years. The effects of losing mangrove habitats will ripple throughout the marine world.

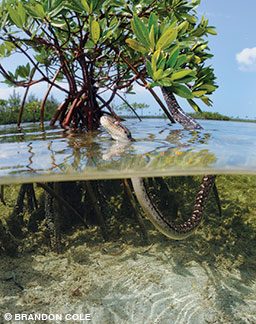

Mangroves live along subtropical and tropical coastlines. Their upper trunk, branches and leaves grow above the waterline, but an extensive network of roots, including stilt-like prop roots, remain mostly underwater. The dozens of mangrove species range in height from 6 feet to 35 feet, all with oblong or oval-shaped leaves that excrete excess salt, enabling the trees to live in high-saline environments.

Dense patches or forests of mangroves provide habitats for a wealth of terrestrial, estuarine and marine species that include invertebrates, fish (including the juvenile stages of commercially important species) and many types of seabirds and waterfowl. The Global Mangrove Alliance, a nongovernmental organization, reports that mangrove forests also provide important shelter as well as feeding and breeding space for 174 marine megafauna species, including dugongs, manatees, dolphins, porpoises, sea turtles, sharks and rays. This teeming life makes mangroves alluring spots for snorkeling and shallow dives. These ecosystems also provide important nutrients and sediments to nearby seagrass beds and coral reefs.

Each year mangrove forests provide at least $1.6 billion in worldwide ecosystem services, such as protecting coastlines against erosion and flooding by absorbing wave and storm-surge energy. Just 100 yards of mangrove forest can reduce wave height by up to 66 percent, according to a report from the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC), The Nature Conservancy and Risk Management Solutions.

In Florida, for example, mangroves prevented an additional $1.5 billion worth of damages from Hurricane Irma in 2017, said Laura Geselbracht, a marine scientist and coastal restoration expert with The Nature Conservancy. Around the globe, flood damages could rise by more than $65 billion annually without mangroves.

These forests also help mitigate climate change, sucking up as much as 6 billion tons of carbon every year and storing it in their soil.

Human activity bears the responsibility for much of the mangrove loss, primarily from cutting the trees for timber, fuel and development, including tourism infrastructure and aquaculture.

Two recent egregious examples include major development projects in Bangladesh and Vietnam. The Sundarbans, the world’s largest mangrove forest, covers almost 4,000 square miles in Bangladesh and India and houses hundreds of wildlife species, including birds, fish, reptiles, amphibians and mammals, among them the endangered Bengal tiger. A planned 3.8-mile-long bridge is expected to bring much more industrial and tourism activity to the area, along with the potential to destroy large swaths of mangroves. A $9.3 billion tourist development planned in Vietnam will be built mainly on filled-in coastal land within a UNESCO Mangrove Biosphere Reserve buffer zone near Ho Chi Minh City.

The trees also are vulnerable to the sea-level rise resulting from climate change. Mangrove roots trap sediment, building up the soil in a process known as accretion that can create entire islands. A recent analysis by scientists in Australia, Hong Kong and Singapore projected that accretion will be unable to keep up with global sea-level rise and in about 30 years mangrove trees will begin to drown.

Fortunately, scientists know a lot about restoring mangroves. “We are better at restoring mangroves than any other coastal habitat,” said Michael Beck, research professor at the UCSC Institute of Marine Sciences. He names projects across Vietnam, the Philippines and Guyana that have restored nearly 400 square miles of the habitat. The Global Mangrove Alliance aims to increase global mangrove habitats by 20 percent by 2030.

The flood protection benefits of mangroves can serve as a major selling point for restoration. In areas that would benefit the most, funds from insurance and disaster recovery, hazard mitigation and climate adaptation programs can be used to support restoration, Beck said.

Divers can help too. Beck suggests supporting local restoration efforts by donating to groups involved in mangrove conservation and restoration and participating as a volunteer where opportunities exist. Those who own land on the coast in subtropical areas such as Florida can plant mangroves instead of building bulkheads; the trees are cheaper, more resilient and less likely to be damaged in a storm.

People living in coastal areas can encourage adoption of cost-effective green measures for coastal defense such as planting mangroves and not just gray efforts such as seawalls. “Pressure and questions from local citizens matter,” Beck said.

Consider offsetting the carbon footprint of your next trip or even your household or business with blue carbon, which is the capacity for marine ecosystems such as seagrasses and mangroves to take up and sequester large quantities of carbon. The Ocean Foundation’s Seagrass Grow has an easy-to-use online calculator for determining an activity’s carbon footprint, which you then can offset by supporting restoration projects worldwide (oceanfdn.org/projects/seagrass-grow). The Ocean Foundation, for example, works on restoration in Jobos Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve in Puerto Rico.

“Mangroves store 10 to 25 times more carbon than terrestrial landscapes — more than the Amazon rainforest — and are less likely to be cut down or burn,” The Ocean Foundation’s Jason Donofrio said. Mangrove forests are thus naturally resistant to destructive actions that release sequestered carbon back into the atmosphere. Jobos Bay being a protected area is important. “Offsetting your carbon footprint doesn’t happen overnight but rather over decades. There is long-term stewardship of this project,” he added.

A typical trip translates to between 0.5 and 1.5 tons of carbon, depending on how far you travel, transportation mode, lodging type and other factors, Donofrio said. Offsetting is $20 per ton.

These kinds of protection and restoration efforts could turn the tide of mangrove loss and its effects on the ocean world.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021