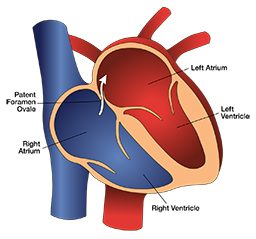

In a paper published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, Jakub Honek and coauthors presented their findings concerning diving with PFO (patent foramen ovale) closures.

To examine PFO closure and susceptibility to DCS, the researchers focused their study on two groups: 19 divers who had large persistent PFOs and 15 divers who had their PFO surgically closed.

The subjects first participated in an 80-minute dry chamber dive to 18 msw. After the dive, 74% of the divers with PFOs and 80% of the divers with closures had venous gas bubbles. Arterial bubbles were detected in 32% of the divers with PFOs and none were detected in the divers with closures. Additionally, 21% of the divers with PFOs demonstrated mild DCS symptoms.

The subjects’ second dive was also a chamber dive, but with divers immersed in water. The dive was for 20 minutes at an equivalent pressure of 50 msw, with decompression following the 1996 edition of the U.S. Navy Tables. After this dive, 88% of the divers with PFOs and 100% of the closure divers had venous bubbles, and 88% of the divers with PFOs and none of the closure divers had arterial bubbles. In the PFO group, 32% demonstrated symptoms of DCS.

This looks like the final answer to the long-standing dilemma about what to do in case a diver is diagnosed with a persistent PFO. However, due to incomplete reporting, this study may spark another debate rather than provide answers.

The following are a few weaknesses in the report, as I see it:

First, divers were only screened for circulating bubbles at one time point during the 60-minute period following each dive at two different sites. They were screened first using transthoracic echocardiography to look for bubbles in the right heart; then, they were screened using transcranial echocardiography to look for arterial bubbles in the cranial arteries. The time lapse between these two screenings was likely very brief. Although it is not likely that the timing of bubble detection alone could account for the outcome so perfectly aligned with the study hypothesis, as in this case, pattern of bubble appearance after dive is usually explored at multiple time points in order to ensure that nothing is missed.

Second, the methods of outcome measurement regarding decompression sickness were either not standardized or not reported.

Third, I am struck by the complete absence of any arterial bubbles in divers with closed PFOs. In other studies, it has been reported that arterialization of bubbles occurs both in divers with persistent PFOs and in divers with naturally sealed PFOs when venous gas bubbles are present in a large degree, as bubbles can move through passages in the lungs. For Honek’s study, the venous bubbles must have been few (the degree of venous gas bubbles was not reported) or divers with large PFOs must have no pulmonary shunts at all.

The weaknesses in this study could be probably clarified by authors, but these questions could have been avoided by more meticulous reporting. Still, this study was a very significant effort and hopefully my criticism will prove irrelevant. If these results can be confirmed in another study, we would be much closer to finding the solution for divers with persistent PFOs.

Resource

Honek J, et all. Catheter-Based Patent Foramen Ovale Closure on the Occurrence of Arterial Bubbles in Scuba Divers. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv 2014.