“Heart disease develops 7 to 10 years later in women than in men.”

Ischemia is a term meaning that an inadequate supply of blood is reaching a part of the body. Ischemic heart disease thus means not enough blood is getting to the heart muscle. It is almost always caused by atherosclerosis (a narrowing of the arteries due to fatty deposits on their inner walls) in the coronary arteries (the arteries that supply the heart muscle), and it is the most common cause of heart disease. The prevalence of ischemia increases with age. The first manifestation of ischemic heart disease is sometimes a fatal heart attack, but the condition’s presence may be signaled by symptoms that should prompt lifesaving actions. Knowing these symptoms can mean living longer. And preventing heart disease in general means living happier — without symptoms or functional limitations.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

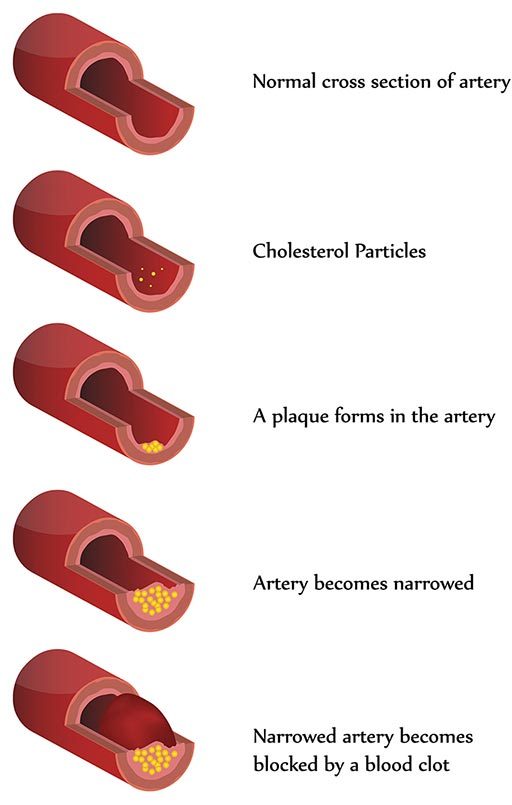

Atherosclerosis

Atherosclerosis is popularly referred to as “hardening of the arteries.” It’s the result of cholesterol and other fatty material being deposited along the inner walls of the arteries. The condition has different manifestations, depending on which arteries are affected; it causes coronary artery disease (CAD) in the heart, cerebrovascular atherosclerosis in the brain and peripheral artery disease (PAD) in the limbs.

The walls of the arteries, in response to the deposition of fatty material, also thicken. The result is a progressive reduction in the flow of blood through the affected vessels. These effects are especially damaging in the heart; CAD is the leading cause of death in the United States and other industrialized countries.

Many factors contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, including a diet high in fat and cholesterol, smoking, hypertension, increasing age and a family history of the condition. Women of reproductive age are generally at lower risk of atherosclerosis due to the protective effects of estrogen.

Medications typically used to treat atherosclerosis include nitroglycerin (which is also used in the treatment of angina, or chest pain) and calcium channel blockers and beta blockers (which are also used in the treatment of high blood pressure, or hypertension; see “Antihypertensives” for more on these drugs). Sometimes, individuals with CAD may need what’s known as a revascularization procedure, to re-establish the blood supply — typically a coronary artery bypass graft or angioplasty. If such a procedure is successful, the individual may be able to return to diving after a period of healing and a thorough cardiovascular evaluation (see “Issues Involving Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts.”).

Effect on Diving

Symptomatic coronary artery disease is not consistent with safe diving: don’t dive if you have CAD. The condition results in a decreased delivery of blood — and therefore oxygen — to the muscular tissue of the heart. Exercise increases the heart’s need for oxygen. Depriving your heart of oxygen can lead to abnormal heart rhythms and/or myocardial infarction, (a heart attack). The classic symptom of CAD is chest pain, especially following exertion. But unfortunately, many people have no symptoms before they experience a heart attack.

A history of stroke — or of “mini strokes” known as transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) — are also, in most cases, not consistent with safe diving.

Cardiovascular disease is a significant cause of death among divers. Older divers and those with significant risk factors for coronary artery disease should have regular medical evaluations and undergo appropriate screening studies, such as a treadmill stress test.

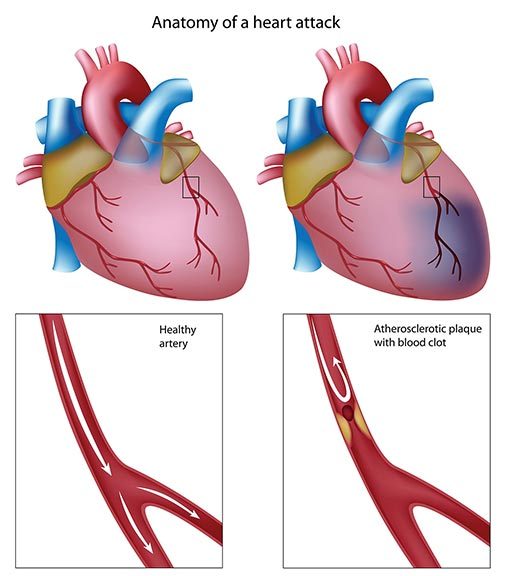

Myocardial Infarction

When any of the arteries supplying the heart become blocked, a myocardial infarction, or heart attack, will occur if the blockage (or “infarct”) is not eliminated quickly. The heart muscle supplied by that artery then becomes starved for oxygen and eventually dies. If the infarct is large enough, the heart’s ability to pump blood is compromised, and circulation to all the body’s other critical organs is affected. The heart’s electrical system may also be adversely affected, resulting in an abnormal rhythm known as ventricular fibrillation.

The main cause of myocardial infarction is coronary artery disease (CAD), or a gradual narrowing of the arteries that supply the heart with blood. Eventually, a piece of the fatty plaques affixed to the arteries’ inner walls may break free and lodge in a smaller vessel, resulting in total occlusion. CAD affects 3 million Americans and kills more than 700,000 each year; it is the most common life-threatening disease. A blockage that results in a myocardial infarction can also be caused by a bubble of gas or a clot within a blood vessel. But, simply stated, whatever the cause of the occlusion, it means the oxygen required by the heart muscle can no longer be supplied through the blocked vessel.

The classic symptoms of myocardial infarction include radiating chest pain (angina) or pain in the jaw or left arm. Other symptoms include heart palpitations; dizziness; indigestion; nausea; sweating; cold, clammy skin; and shortness of breath.

If a myocardial infarction is suspected, it is essential that emergency medical care be called and the affected individual evacuated to a hospital. In the meantime, keep the individual calm and administer oxygen. At the hospital, the treatment options include conservative medical management, anticoagulation drugs, heart catheterization or stenting or even coronary artery bypass surgery.

Preventing myocardial infarction calls for addressing any risk factors, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension or smoking. A healthy diet and regular exercise are also important preventatives.

Effect on Diving

Anyone with active ischemic CAD should not dive. The physiologic changes involved in diving, as well as the exercise and stress of a dive, may initiate a cascade of events leading to a myocardial infarction or to unconsciousness or sudden cardiac arrest while in the water. Divers who have been treated and evaluated by a cardiologist may choose to continue diving on a case-by-case basis; essential aspects of such an evaluation include the individual’s exercise capacity and any evidence of ischemia while exercising, of arrhythmias or of injury to the heart muscle.

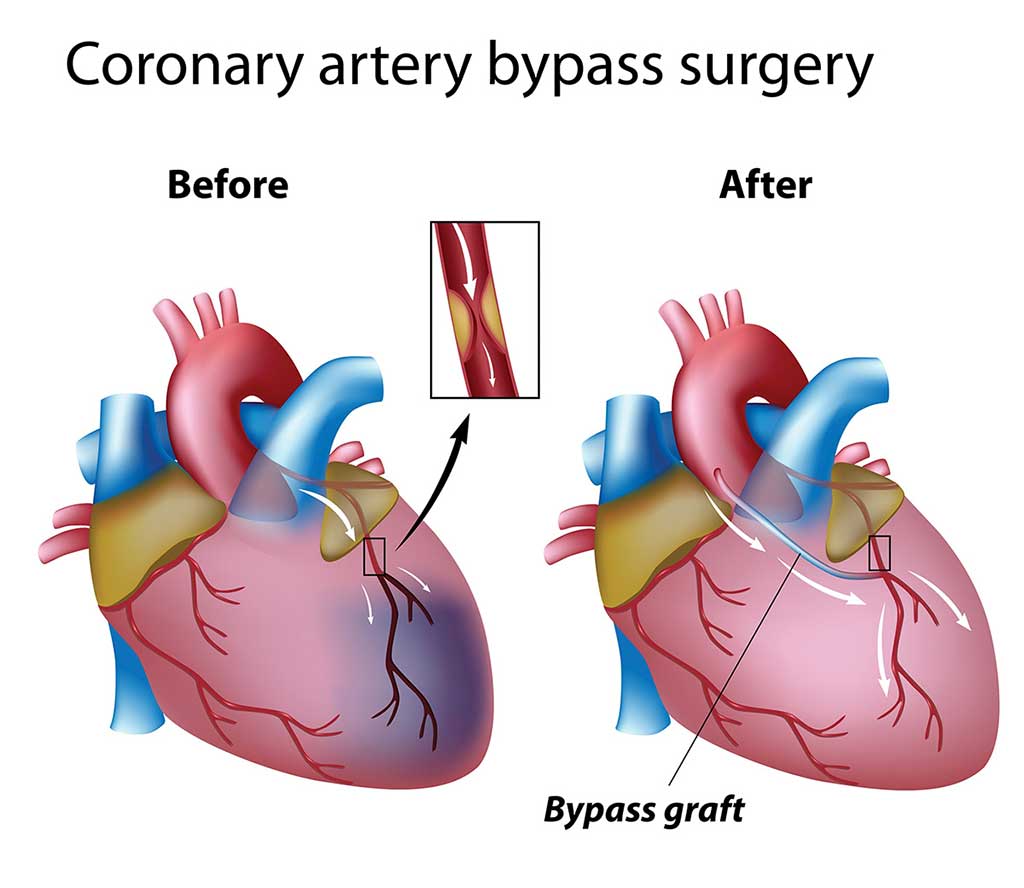

Coronary Artery Bypass Grafts

A coronary artery bypass is the surgical correction of a blockage in a coronary artery; it is accomplished by attaching (or “grafting”) onto the damaged vessel a piece of a vein or artery from elsewhere in the body, so as to circumvent the blockage.

Doctors perform this procedure many hundreds of times a day, all around the country — more than half a million times a year. If a bypass is successful, the individual should be free of the symptoms of coronary artery disease, and the heart muscle should once again receive a normal supply of blood and thus oxygen.

A blocked coronary artery can also be treated with a less invasive procedure, coronary angioplasty. It consists of inserting a catheter with a tiny balloon on its tip into the area of the blockage, then inflating the balloon to open the artery. This procedure does not require opening the chest and can be performed in an outpatient setting.

Effect on Diving

Individuals who have had a coronary artery bypass graft or coronary angioplasty may have suffered significant cardiac damage prior to having surgery. Their postoperative cardiac function is what determines their fitness for a return to diving.

In particular, those who have had open-chest surgery need to have a thorough medical evaluation prior to diving again. After a period of stabilization and healing (6 to 12 months is the usual recommendation), such individuals should have a complete cardiovascular evaluation before being cleared to dive. They should be free of chest pain and have a normal tolerance for exercise, as evidenced by a normal stress EKG test (at 13 METs, as described in “Calculating Physical Activity Intensity”). If there is any doubt about the success of the procedure, or how open the coronary arteries are, the individual should refrain from diving.

Issues Particular to Women

Heart disease is the leading cause of death in women, and myocardial infarction (heart attack) is the leading cause of their hospitalization. The characteristics of the disease in women may differ from those in men; the age of onset, presence of risk factors, probability of aggressive diagnosis and even likelihood of appropriate treatment vary in men and women.

For example, heart disease develops 7 to 10 years later in women than in men (possibly because of the protective effect of estrogen). Myocardial infarction is less frequent in young women than in young men, but young women who have a heart attack are at greater risk of dying within 28 days of their attack. The common risk factors for heart disease have a similar predictive value for men and women; however, men more frequently have smoking as a risk factor, whereas women more frequently have hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia or angina. Although women typically smoke less than men, the relative risk for myocardial infarction in women who do smoke is 1.5 to 2 times greater than in men who smoke, especially in those less than 55 years old. A higher prevalence of diabetes also contributes to higher mortality rates from heart attacks among women.

Women receive fewer advanced diagnostic tests such as coronary angiography and fewer interventions such as coronary artery bypass grafts. These differentials may be due to the fact that acute heart attacks are likely to occur at an older age in women, or to the presence of other associated diseases, but could also be due to delays in admitting women to the hospital.

The symptoms of a heart attack in women are usually the same as those in men, with chest pain (angina) being the leading symptom. However, women are more likely to attribute their symptoms to acid reflux, the flu or normal aging. In addition, the chest pain that women experience does not necessarily occur in the center of the chest or the left arm; instead, women may feel pressure in their upper back — a sensation of squeezing or as if a rope is tied around them.

Although 90 percent of women who suffer a heart attack later admit that they intuitively knew that was the cause of their symptoms, at the time they often discount them, attribute them to something else, take an aspirin or just delay calling 911. This decreases the opportunity to preserve their heart from damage and lowers their chance of survival.

These are the most common symptoms of a heart attack in women:

- Uncomfortable pressure, squeezing, fullness or pain in the center of the chest; it lasts more than a few minutes or goes away and comes back

- Pain or discomfort in one or both arms, the back, neck, jaw or stomach

- Shortness of breath, with or without chest discomfort

- Other signs, such as breaking out in a cold sweat, nausea or lightheadedness

- As with men, women’s most common heart attack symptom is chest pain or discomfort — but women are somewhat more likely than men to experience some of the other common symptoms, particularly shortness of breath, nausea/vomiting or back or jaw pain.

Source: American Heart Association