“By 2050, it is estimated that atrial fibrillation (AFib) will affect between 5.6 million and 12 million Americans.”

The electrical wiring of your heart — which controls the rate at which your heart beats, every minute, hour and day, 365 days a year — is one of the most sophisticated and enduring pieces of nature’s engineering. However, there are some irregularities that can occur in that wiring as well as damage that can be caused by disease, all of which can cause symptoms and increase the risk of premature death. Divers, and any physicians who treat them, should be familiar with arrhythmias and their effects on the safety of scuba divers.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

- Overview of Arrhythmias

- Syncope

- Extrasystole

- Atrial Fibrillation

- Sudden Cardiac Arrest

- Issues Involving Implanted Pacemakers

Overview of Arrhythmias

The term “arrhythmia” (or, sometimes, “dysrhythmia”) means an abnormal heartbeat. It is used to describe manifestations ranging from benign, harmless conditions to severe, life-threatening disturbances of the heart’s rhythm.

A normal heart beats between 60 and 100 times a minute. In well-trained athletes, or even select nonathletic individuals, the heart may beat at rest as slowly as 40 to 50 times a minute. Even entirely healthy, normal individuals experience occasional extra beats or minor changes in their heart’s rhythm. These can be caused by drugs (such as caffeine) or stress or can occur for no apparent reason. Arrhythmias become serious only when they are prolonged or when they do not result in proper contraction of the heart.

Physiologically significant extra heartbeats may originate in the upper chambers of the heart (this is called “supraventricular tachycardia”) or in the lower chambers of the heart (this is called “ventricular tachycardia”). The cause of these extra beats may be a short circuit or an extra conduction pathway in the heart’s wiring, or it may be the result of some other cardiac disorder. People who have episodes or periods of rapid heartbeat are at risk of losing consciousness during such events. Other people have a fairly stable arrhythmia (such as “fixed atrial fibrillation”) but in conjunction with additional cardiovascular disorders or other health problems that exacerbate the effect of their rhythm disturbance. A too-slow heartbeat (or a heart blockage) may cause symptoms, too.

Effect on Diving

Serious arrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia and many types of atrial arrhythmia, are incompatible with diving. The risk for any person who develops an arrhythmia during a dive is, of course, losing consciousness while underwater. Supraventricular tachycardia, for example, is unpredictable in its onset and may even be triggered simply by immersing one’s face in cold water. Anyone who has had more than one episode of this type of arrhythmia should not dive.

Most arrhythmias that require medication also disqualify the affected individual from safe diving. Exceptions may be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with a cardiologist and a diving medical officer.

An individual who has any cardiac arrhythmia needs a complete medical evaluation by a cardiologist prior to engaging in diving. In some cases, electrophysiologic studies can identify an abnormal conduction pathway, and the problem can be corrected. Recently, clinicians and researchers have determined that people with some arrhythmias (such as certain types of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, which is characterized by an extra electrical pathyway) may safely participate in diving after a thorough evaluation by a cardiologist. Also, in select cases, people with stable atrial arrhythmias (such as uncomplicated atrial fibrillation) may dive safely if a cardiologist determines that they have no other significant health problems.

Syncope

Syncope is an abrupt loss of consciousness followed by a relatively quick recovery. The causes of syncope range from relatively benign to life-threatening. It is seldom overlooked and usually precipitates a visit to a medical professional.

Syncope that occurs in or around the water poses particular challenges. Drowning often results when a diver loses consciousness and remains in the water. A rapid response is required to bring an unconscious diver to the surface and prevent death. Syncope can also occur upon exiting the water, due to such factors as exertion, dehydration and normal return of blood volume to the lower extremities.

The initial response to syncope should focus on the ABCs of basic life support: airway, breathing and circulation. Advanced cardiac life support may be called for. Often, placing syncopal patients flat on their back in a cool environment will quickly restore them to consciousness. If syncope occurs following a dive, it is important to consider decompression sickness, pulmonary overinflation and immersion pulmonary edema in addition to the usual causes of the condition. Although both syncope and cardiac arrest result in a loss of consciousness, they can usually be clearly differentiated.

The list of possible causes of syncope is extensive, but a good medical history can help eliminate the majority of them. The patient’s age, heart rate, family history, medical conditions and medications are key in identifying the cause. If syncope is accompanied by convulsions (known as “tonic-clonic movements”), it may have been precipitated by a seizure. If it occurs upon exertion, a serious cardiac condition may be preventing the heart from keeping up with the demands of the physical activity; chest pain may be associated with this type of syncope. If standing up quickly results in syncope, that points to a cause known as “orthostatic hypotension.” And pain, fear, urination, defecation, eating, coughing or swallowing may cause a variation of the condition known as “reflex syncope.”

A medical evaluation after an incident of syncope should include a thorough history and physical — plus interviews with witnesses who observed the individual’s collapse and who can accurately relay the sequence of events. A few cases may require more extensive investigation, and some result in no conclusion.

Effect on Diving

While a medical evaluation is being conducted, it is recommended that the affected individual refrain from any further diving. The cause of a given syncopal episode can be elusive but must be pursued — especially if the individual hopes to return to diving. Once the underlying factors have been determined, a diving medical officer and appropriate specialists should consider whether diving can be resumed safely.

Extrasystole

Heart beats that occur outside the heart’s regular rhythm are known as “extrasystoles.” They often arise in the ventricles, in which case they are referred to as “premature ventricular contractions” or sometimes “premature ventricular complexes,” abbreviated as PVCs. The cause of such extra beats can be benign or can result from serious underlying heart disease.

PVCs are common even in healthy individuals; they have been recorded in 75 percent of those who undergo prolonged cardiac monitoring (for at least 24 hours, that is). The incidence of PVCs also increases with age; they have been recorded in more than 5 percent of individuals more than 40 years old who undergo an electrocardiogram (or ECG, a test that typically takes less than 10 minutes to administer). Men seem to be affected more than women.

The extrasystole itself is usually not felt. It is followed by a pause — a skipped beat — as the heart’s electrical system resets itself. The contraction following the pause is usually more forceful than normal, and this beat is frequently perceived as a palpitation — an unusually rapid or intense beat. If extrasystoles are either sustained or combined with other rhythm abnormalities, affected individuals may also experience dizziness or lightheadedness. Heart palpitations and the sensation of missed or skipped beats are the most common complaints of those who seek medical care for extrasystole.

A medical examination of the condition begins with a history and physical and should also include an ECG and various laboratory tests, including the levels of electrolytes (such as sodium, potassium and chloride) in the blood. In some cases, doctors may recommend an echocardiogram (an ultrasound examination of the heart), a stress test and/or the use of a Holter monitor (a device that records the heart’s electrical activity continuously for a 24- to 48-hour period). Holter monitoring may uncover PVCs that are unifocal — that is, they originate from a single location. Of greater concern are multifocal PVCs — those that arise from multiple locations — as well as those that exhibit specific patterns known R-on-T phenomenon, bigeminy and trigeminy.

If serious structural disorders, such as coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathy (a weakening of the heart muscle), can be ruled out — and the patient remains asymptomatic — the only “treatment” required may be reassurance. But for symptomatic patients, the course is less clear, as there is controversy regarding the effectiveness of the available treatment options. Two drugs commonly used to treat high blood pressure — beta blockers and calcium channel blockers — have been used in patients with extrasystole with some success. Antiarrhythmics have also been prescribed for extrasystole but have met with mixed reviews. A procedure known as cardiac ablation may be an option for symptomatic patients, if the location where their extra beats arise can be identified; the procedure involves threading tiny electrodes into the heart via catheters, then zapping the affected locations to rewire the heart’s faulty circuits.

Effect on Diving

Although PVCs are present in a large percentage of otherwise normal individuals, they have been shown to increase mortality over time. If PVCs are detected, it is important that they be investigated and that known associated conditions be ruled out. Divers who experience PVCs and who are found to also have coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathy will put themselves at significant risk if they continue to dive. Divers diagnosed with R-on-T phenomenon, nonsustained runs of ventricular tachycardia or multifocal PVCs should likewise refrain from diving. Divers who experience PVCs but remain asymptomatic may be able to consider a return to diving; such individuals should discuss with their cardiologist their medical findings, their desire to continue diving and their clear understanding of the risks involved.

Atrial Fibrillation

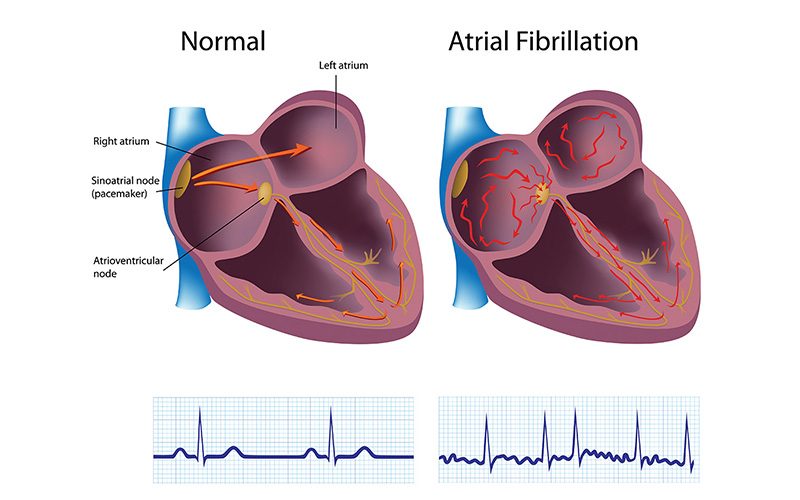

Atrial fibrillation (AF or AFib), the most common form of arrhythmia, is characterized by a fast and irregular heartbeat. It results from a disturbance of the electrical signals that normally make the heart contract in a controlled rhythm. Instead, chaotic and rapid impulses cause uncoordinated atrial filling and ventricle pumping action. This leads to a decrease in overall cardiac output, which can affect one’s exercise capacity or even result in unconsciousness. In addition, AF causes blood to pool in the atria, which promotes the formation of blood clots that may break loose and enter the circulatory system; if this occurs, it may result in a stroke.

Recent U.S. studies have shown a rising incidence of AF overall as well as significant racial differences in its prevalence. The lifetime risk of AF (at 80 years of age) was recently found to be 21 percent in white men and 17 percent in white women but only 11 percent in African-Americans of both sexes. By 2050, it is estimated that AF will affect between 5.6 million and 12 million Americans. These figures are significant, because AF is associated with a fourfold to fivefold higher risk of ischemic stroke. Individuals with AF, after adjustment for other risk factors, also have a twofold higher risk of dementia.

The most common causes of AF are hypertension and coronary artery disease. Additional causes include a history of valvular disorders, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (a thickening of the heart’s muscle), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, obesity, hyperthyroidism (also called “overactive thyroid”), heavy alcohol consumption, an imbalance of electrolytes in the blood, cardiac surgery and heart failure.

Some people with AF experience no symptoms and are unaware they have the condition until it’s discovered during a physical examination. Others may experience symptoms such as the following:

- Palpitations (a racing, uncomfortable, irregular heartbeat or a flip-flopping sensation in the chest)

- Weakness

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Fatigue

- Lightheadedness

- Dizziness

- Confusion

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

The occurrence and duration of atrial fibrillation usually falls into one of three patterns:

- Occasional (or “paroxysmal”): The rhythm disturbance and its symptoms come and go, lasting for a few minutes to a few hours, and then stop on their own. Such events may occur a couple of times a year, and their frequency typically increases over time.

- Persistent: The heart’s rhythm doesn’t go back to normal on its own, and treatment — such as an electrical shock or medication — is required to restore a normal rhythm.

- Permanent: The heart’s rhythm can’t be restored to normal. Treatment may be required to control the heart rate, and medication may be prescribed to prevent the formation of blood clots.

Any new case of AF should be investigated and its cause determined. An investigation may include a physical exam; an electrocardiogram; a measurement of electrolyte levels, including magnesium; a thyroid-hormone test; an echocardiogram; a complete blood count; and/or a chest X-ray.

Treating the underlying cause of AF can help control the fibrillation. Various medications, including beta blockers, may help regulate the heart rate. A procedure known as cardioversion — which can be performed with either a mild electrical shock or medication — may prompt the heart to revert to a normal rhythm; before cardioversion is attempted, it is essential to ensure that a clot has not formed in the atrium. Cardiac ablation, which is described in the “Extrasystole” section, may also be used to treat AF. In addition, anticoagulant drugs are often prescribed for individuals with AF to prevent the formation clots and thus reduce their risk of stroke. It is also of note that the neurological effects of an embolic stroke associated with AF can sometimes be confused with the symptoms of decompression sickness.

Effect on Diving

A thorough medical examination should be conducted to identify the underlying cause of the atrial fibrillation. It is often the underlying cause that is of most concern regarding fitness to dive. But even atrial fibrillation itself can have a significant impact on cardiac output and therefore on maximum exercise capacity. Individuals who experience recurrent episodes of symptomatic AF should refrain from further diving. The medications often used to control atrial fibrillation can present their own problems, by causing other arrhythmias and/or impairing the individual’s exercise capacity. It is essential that anyone diagnosed with AF have a detailed discussion with a cardiologist before resuming diving.

Sudden Cardiac Arrest

Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) — a cessation of the heart’s beating action, with little or no warning — is an acute medical emergency. During the arrest, blood stops circulating to the body’s vital organs, including the brain, the kidneys and the heart itself. Cut off from oxygen, these organs die within minutes. If the arrest is not corrected quickly, the affected individual will not survive.

The causes of SCA include myocardial infarction (heart attack), heart failure, drowning, coronary artery disease, electrolyte abnormalities, drugs, abnormalities in the heart’s electrical conduction system, cardiomyopathy (a weakening of the heart muscle) and embolism (a clot that has lodged in a major vessel).

SCA accounts for 450,000 deaths in the United States each year and for 63 percent of cardiac deaths in Americans more than 35 years old. The risk of sudden cardiac death in adults increases as much as sixfold with increasing age, paralleling the rising incidence of ischemic heart disease. The risk of SCA is greater in those with structural heart diseases, but in 50 percent of sudden cardiac deaths the victim had no awareness of having heart disease, and in 20 percent of autopsies conducted following such deaths, no structural cardiovascular abnormalities were found.

Though there is typically little warning before a sudden cardiac arrest, occasionally the individual may experience lightheadedness, difficulty breathing, palpitations or chest pain.

Immediate treatment should be focused on restoring circulation quickly using chest compressions or CPR and defibrillation. Following resuscitation, the victim should be transported to a hospital as soon as possible. Subsequent treatment may consist of efforts to eliminate the underlying cause of the arrest through administration of medication, surgery or the use of implanted electrical devices.

Preventive strategies include learning to recognize the warning signs of SCA, in case they occur; identifying, eliminating or controlling any risk factors that may affect you; and scheduling regular physical exams, as well as appropriate testing, when it is indicated.

Effect on Diving

Divers with any symptoms of cardiovascular disease should be evaluated by a cardiologist and a dive-medicine specialist regarding their continued participation in diving. In asymptomatic individuals, the risk of SCA may be evaluated by using known cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, lack of exercise and overweight. For example, people who smoke have two and a half times the risk of suffering sudden cardiac death than do nonsmokers.

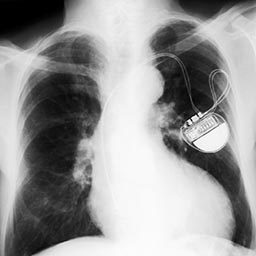

Issues Involving Implanted Pacemakers

A pacemaker is a small battery-operated device that helps an individual’s heart beat in a regular rhythm. It does this by generating a slight electrical current that stimulates the heart to beat. The device is implanted under the skin of the chest, just below the collarbone, and is hooked up to heart with tiny wires that are threaded into the organ through its major vessels. In some individuals, the heart may need only intermittent help from the pacemaker, if the pause between two beats becomes too long. In others, however, the heart may depend completely on the pacemaker for regular stimulation of its beating action.

Effect on Diving

Every case involving a pacemaker must be evaluated individually. The two most important factors to take into account are the following:

- Why is the individual dependent on a pacemaker?

- Is the individual’s pacemaker rated to perform at depths (in other words, pressures) compatible with recreational diving — plus an added margin of safety?

The reason for the second factor is that a pacemaker is implanted in tissues just under the skin and thus is exposed during a dive to the same ambient pressures as the diver. For safe diving, a pacemaker must be rated to perform at a depth of at least 130 feet (40 meters) and must also operate satisfactorily during conditions of relatively rapid pressure changes, such as would be experienced during ascent and descent.

As with any medication or medical device, the underlying problem that led to the implantation of the pacemaker is the most significant factor in determining someone’s fitness to dive. The need to have a pacemaker implanted usually indicates a serious disturbance in the heart’s own conduction system.

If the disturbance arose from structural damage to the heart muscle itself, as is often the case when someone suffers a major heart attack, the individual may lack the cardiovascular fitness to dive safely.

Some individuals, however, depend on a pacemaker not because the heart muscle has been damaged but simply because the area that generates the impulses which make the heart muscle contract does not function consistently or adequately. Or the circuitry that conducts the impulses to the heart muscle may be faulty, resulting in improper or irregular signals. Without the assistance of a pacemaker, such individuals might suffer episodes of syncope (fainting). Others may have suffered a heart attack mild enough that they sustained minimal residual damage to their heart muscle, but their conduction system remains unreliable and thus needs a boost from a pacemaker.

If a cardiologist determines that an individual’s level of cardiovascular fitness is sufficient for safe diving, and the individual’s pacemaker is rated to function at a pressure of at least 130 feet (40 meters), that individual may be considered fit for recreational diving. But once again, it cannot be emphasized strongly enough that any divers with cardiac issues check with their doctor before diving.