SHARING SPACE WITH WILD ANIMALS in nature is one of the greatest gifts life has to offer. Maybe you’ve locked eyes with an orangutan in Borneo, or perhaps you’ve watched a clownfish gently tend its eggs on a reef. You may have spied an army of leafcutter ants marching plant clippings back to its colony or peered over the bow of a boat only to catch the gaze of a dolphin.

No matter the size of the creatures you encounter or the rarity of the species, each opportunity to open a window into the existence of these fellow earthlings is a privilege.

Underwater environments amplify the weight of that privilege. As terrestrial mammals, we need a fair bit of assistance to survive in water, even for relatively short periods. This barrier greatly diminishes the number of close interactions people have with ocean wildlife, making each meeting more meaningful. Marine mammal encounters make that phenomenon particularly evident since the likelihood of sharing an underwater moment with these seagoing beings is so low.

Blue whales are shy and fully focused on their migration. To capture this intimate closeup, the photographer sat in a kayak for hours off San Diego, California, until he was able to get close to one. He then placed his camera in the water and blindly captured this image that he had imagined. © AMOS NACHOUM

To be in the presence of a blue whale might be one of the most profoundly soulful experiences on Earth, and to be so fortunate as to have a camera to capture that moment in time is the very definition of priceless.

Blue whales (Balaenoptera musculus) are not only the largest animals alive today but also the biggest ones that have ever lived on Earth. We are wildly lucky to exist at the same time as this oceanic colossus.

It is difficult to imagine just how huge these whales are until you’re in the water with them. They weigh as much as 200 tons and typically grow to 80 to 90 feet long. A 2021 study by Stanford University indicates that in a single day adult blue whales can consume between 10 and 20 tons of plankton, and krill is their primary food source.

Classified as a rorqual — the largest group of baleen whales — this whale has a huge mouth filled with up to 400 baleen plates, which it uses to filter plankton from the seawater. They feed by gulping gigantic volumes of water containing krill into their mouths and then forcing the water out while plankton remains trapped in the baleen.

Blue whales inhabit all the world’s oceans except the Arctic, and most undertake monumental migrations toward the poles in the summer and the equator in the winter. They can produce loud and low-frequency noises that allow them to communicate with one another over vast distances. Their calls can reach 188 decibels — louder than a jet engine — and travel up to 1,000 miles.

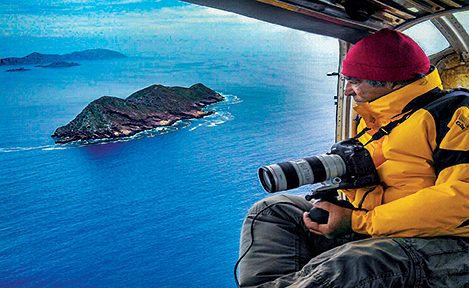

Amos Nachoum makes a scouting flight over Coronado Island, California, to identify whales migrating north from Mexico.

Their average life span is between 80 and 90 years, but the oldest recorded blue whale was estimated to be 110 years old. They are one of Earth’s longest-lived animals and as such have a correspondingly low reproductive rate. They reach sexual maturity between 5 and 15 years old, and females give birth to a single calf once every two to three years after a gestation period of about one year. Calves can weigh up to 3 tons and measure nearly 25 feet at birth.

Due to their highly migratory lifestyle, tracking them and getting an accurate estimate of their population is difficult. The current blue whale population is estimated to be 10,000 to 25,000 worldwide. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List classifies them as endangered, a designation resulting from a century of brutal exploitation for their oil. The historical population of blue whales was near extinction by the mid-20th century, but they finally became protected from commercial whaling in 1966 by the International Whaling Commission, which placed a moratorium on the practice 20 years later.

In the early 20th century there were more than 300,000 blue whales. Commercial whaling decimated the population, and only about

17,000 remain today. © AMOS NACHOUM

Recovery is a slow process, but we are seeing progress. With important rules and regulations in place, blue whales globally are now up to between 3 percent and 11 percent of their historical population. They are gradually rebounding, and many management practices and fishing regulations now fully protect them, but promoting these blue giants’ further protection and conservation is critical.

Unfortunately, the oceans contain far more threats than when whalers roamed the high seas. Blues must contend with rampant marine debris, ship strikes, intense noise pollution, and a declining food supply due to warming waters and commercial krill use, making the whales’ continued recovery tenuous at best.

This species is rebounding much slower compared with other species — such as gray, humpback, and fin whales — since the end of large-scale commercial whaling, and ship strikes may be a significant factor.

“Only a small proportion of large whale mortality is documented as strandings because most large whales sink or do not wash ashore,” reports the Cascadia Research Collective, a nonprofit founded by research biologist John Calambokidis. “True mortality has been estimated to be at least 10 times higher than suggested by the documented strandings.”

Calambokidis is widely respected for his contributions to whale research and conservation. His shipping-lane research resulted in changing the routes of ships traveling to California ports to steer them away from where whales congregate.

“I’ve focused not only on doing the research to reduce ship strikes but also working with industry and government agencies to implement changes,” Calambokidis said. While the shifts are a good start in reducing the incidence of strikes, he said more still needs to be done, including slowing down the vessels.

Marine debris is another major issue for blue whales, one that has reached plague proportions in our world’s waters. Human garbage big and small has infiltrated and polluted every marine habitat from the equator to the poles. Blue whales encounter marine debris in many forms, including microplastics, massive ghost fishing nets, and everything in between.

A paper published in the journal Nature Communications in 2022 estimates that a blue whale may consume up to 10 million pieces of microplastic every day during its main feeding season. That adds up to close to 100 pounds of plastic daily. The study authors, however, reported that only 1 percent of the plastics that baleen whales swallow comes directly from the water they filter out of their mouths. The prey items the whales eat have already ingested the other 99 percent.

Another problem results when old, broken, or entangled fishing gear is dumped in the ocean, creating ghost fishing gear. These ghost nets are the most harmful form of marine debris and can drift with ocean currents for years or even decades, leaving a trail of destruction in their wake. As many as 60 percent of the blue whales in Canada’s Gulf of St. Lawrence have had interactions with fishing ropes and nets based on scarring shown in drone photographs. Due to their size, blues are usually able to break free and survive, but that certainly doesn’t mean they haven’t suffered undue trauma and stress. This obstacle is not negligible for a species that is already struggling to survive.

These are far from the only hardships blue whales face, but due to the inherent difficulty in studying these gigantic pelagic animals, there is a paucity of conclusive data that can detail the specific negative effects of other threats such as noise pollution, increasing water temperatures, and ocean acidification. These factors have measurable negative impacts on a wide range of other marine species, so it seems logical that the same hazards would also prove stressful to blue whales.

A diver swims with a blue whale near Trincomalee, Sri Lanka. © AMOS NACHOUM

Many things we do in the name of progress are harmful to our world and the life it sustains, ourselves included. Whales deserve our protection and respect not only because of their intrinsic value but also because they play a crucial role in how our planet functions.

Michael Fischbach, executive director of the Great Whale Conservancy, explains that whales help stimulate plankton production, which in turn produces more oxygen to offset the impacts of climate change. “For the health of the oceans, we really need more whales,” he said.

A report published by the International Monetary Fund in 2019 supports that statement: “When it comes to carbon, one whale is worth thousands of trees. Whales help to regulate the climate by enhancing phytoplankton growth at the ocean surface, which captures 37 billion tons of CO2 [carbon dioxide] per year.”

Blue whales are many things: majestic, massive, strong, fragile, mysterious, endangered, and critical. But most of all, they are worthy — worthy of lives free from the myriad anthropogenic hazards we have thrust upon them. We owe it to them, and we owe it to ourselves. We must yet again work to save the whales, not just for their sake but for ours as well. AD

© Alert Diver — Q3 2023