DAN medical information specialists and researchers answer your dive medicine questions.

My 13-year-old son recently completed his Junior Open Water Diver certification, which provided training to a maximum depth of 60 feet. The Advanced Junior Open Water Diver certification is good to 70 feet. I understand there are physiological differences between a child and an adult, but what is the rationale for the depth limits?

Opinions vary among dive medicine experts about how to mitigate the complex issues around children and diving, such as age requirements, training levels and limitations. Children are still developing both physically and mentally, which affects the decision about whether a young diver is fully capable or requires some modification. Some training agencies allow in-water experiences for children as young as 8 years old and certification by age 10.

Concerns about decompression sickness (DCS), out-of-air emergencies and gas toxicities that occur at greater depths affect depth-limitation guidelines, which vary among the training agencies. Along with DCS is the theoretical concern that bubbles from a dive could occur in and injure an epiphysis (the rounded end of a long bone). In children up to age 18, bones continue to grow from the physis (growth plate), which in long bones (arms and legs) is near each end. This area, which is quite vulnerable and consists mostly of cartilage, depends on the diffusion of vital substances to and from adjacent tissues that have a blood supply.

An injury to this area could result in abnormal bone growth. The main causes of injuries to this region are from activities such as skiing, rollerblading, ice skating and football. Fortunately, no evidence exists of this growth-inhibition injury in young scuba divers, which may be the result of the safety measures imposed along with strict compliance by parents, guardians and dive operators. Decompression stress exists in most dives and at any age.

Other concerns about children and diving involve their maturity level, ability to handle the weight of the gear, higher risk of barotrauma, susceptibility to dehydration, vulnerability to hypothermia, ability to do a self-analysis and willingness to accept risk. While a child’s maturity can be difficult to assess, questions such as whether you would allow that child to drive a car on the open highway (if trained and the law allowed it) starkly addresses the issue of maturity and judgment. Additionally, most children will not understand the significance of a subtle symptom or risky situation and may be reluctant to timely convey their concerns. Close, adult supervision is necessary.

Comprehensive studies involving children are rare and extremely difficult because of the need for approval from an ethics committee or institutional review board (IRB), which is responsible for protecting the welfare, rights and privacy of human subjects and reviewing all research involving human participants. With more children diving, however, more data are being compiled.

— Robert Soncini, NR-P, DMT

I had a Watchman device implanted after developing atrial fibrillation (AFib). My cardiac ejection fraction is normal, and I no longer take blood thinners but am still in AFib. I take medications for elevated blood pressure but am otherwise in excellent physical condition. Can I return to diving?

Fulfilling the metabolic needs of a diver depends on the heart’s ability to deliver an adequate cardiac output to the rest of the body. AFib, a common heart-rhythm abnormality affecting millions of people, impairs this crucial delivery. The heart’s natural pacemaker, called the sinoatrial (SA) node, usually fires impulses at 60–100 beats per minute that cause the left and right atria to simultaneously contract and fill the ventricles. The impulse then slows when going through the atrioventricular (AV) node, allowing time for the ventricles to fill with blood. The impulse continues into the left and right ventricles, causing them to simultaneously contract.

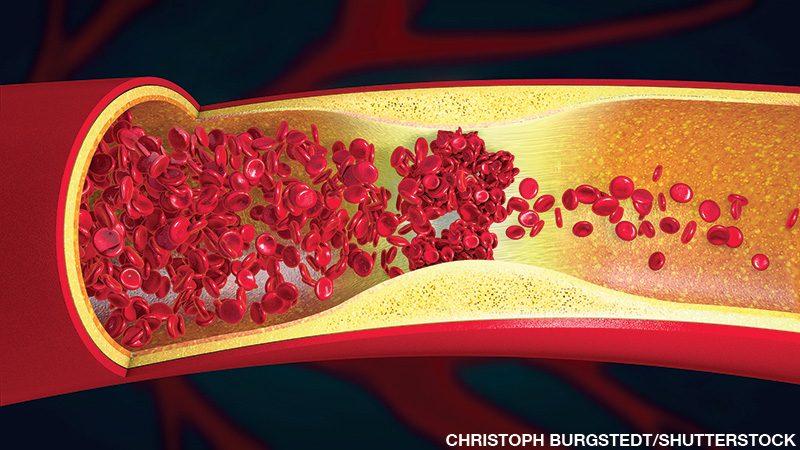

In AFib, however, the atria fire off impulses at a higher rate (up to 300 beats per minute), which causes the upper chambers of the heart to quiver, creating an irregular and chaotic atrial rhythm. The AV node cannot transmit at such a high rate; the speed at which it can transmit these impulses varies by patient depending on factors such as age, medications and other medical conditions. The AV node transmits what impulses it can to the ventricles, resulting in an irregular pulse. The atrial contractions lose their effectiveness in maximizing blood to the ventricles, decreasing the cardiac output and reducing the maximal exercise capacity if it persists.

The quivering action of the atria can cause blood to pool in the left atrium appendage. This pooled blood may begin to clot, and the clots can be pumped to the brain, resulting in a stroke. Interventional cardiologist Dr. Douglas Ebersole, who is also an avid diver and dive instructor, reports that people who develop AFib increase their risk of a stroke fivefold. To mitigate this risk, physicians often prescribe blood thinners or anticoagulants, which can decrease the risk of a stroke by 60–70 percent but increase the risk of hemorrhage.

Some patients, however, are unable to tolerate long-term anticoagulation therapy due to prior bleeding or a high risk of bleeding due to health or occupational conditions. The Watchman device is indicated for those patients who have a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 3 or more. The CHA2DS2-VASc score uses age, gender and other medical conditions to estimate an individual’s stroke risk. Scuba diving alone is not a reason to get a Watchman device and be exposed to the inherent risks of the procedure, Dr. Ebersole advises.

Approximately 45 days after surgeons implant the Watchman device in the left atrial appendage of the heart, tissue that has grown over the device closes off the appendage, stopping any clots from escaping and entering circulation. Most patients are able to return to full activity about a week after the procedure and will need to take anticoagulants and aspirin for 45 days and then transition to an aspirin and clopidogrel for several months before transitioning to just aspirin.

Divers who have AFib should be well rate controlled, both at rest and when performing moderate exercise, and understand the possible complications of their condition before considering diving. We recommend not diving while taking anticoagulants.

Discuss your condition and current medications with a physician trained in dive medicine to understand the risks associated with diving. If the physician approves your return to diving, be cautious and dive near a facility that can provide adequate medical care should a bleeding problem occur. Contact DAN for a referral to a dive medicine physician near you.

— Robert Soncini, NR-P, DMT

I want to get my open-water certification, but I have Factor V and need a doctor to sign my medical form.

The goal isn’t to find a physician to sign off on your ability to dive but rather to objectively determine whether your medical history, Factor V in your case, is compatible with diving. Many health-care providers don’t fully understand how much compressed-gas diving changes an individual’s physiology; those physiological changes affect almost all body systems.

Diving has additional considerations that aren’t an issue for land-based sports. Aquatic activities can be inherently dehydrating, which when combined with altered coagulation creates a complex question that is difficult to answer. No specific studies have attempted to quantify the risks associated with diving by hypercoagulable individuals or how to address those risks.

Factor V Leiden is a gene mutation that increases an individual’s risk of developing abnormal blood clots (thrombophilia). These blood clots typically form in the larger blood vessels of the legs, referred to as deep vein thrombosis (DVT). Blood clots can travel through the blood vessels and lodge in the lungs (pulmonary embolism), causing shortness of breath, chest pain and even death. Physicians prescribe anticoagulant medication to reduce the risk of blood clots.

Separate from the underlying diagnosis are the risks associated with anticoagulants and diving, specifically the higher bleeding risk in closed spaces such as the ears and sinuses. There is also the theoretical concern of worsening a serious DCS event with an additional hemorrhage risk that might adversely affect these central nervous system lesions.

Individuals with the Factor V gene mutation are at an increased risk for developing Factor V Leiden thrombophilia, but most dive medicine physicians agree that those who are completely asymptomatic with no history of clots can be screened individually and generally provided clearance to dive, barring any other unrelated issues. People taking anticoagulants, however, generally should not dive. Your hematologist can contact us for a consultation.

— Lana P. Sorrell, MBA, EMT, DMT

I am a scuba instructor at a resort that offers introductory scuba experiences. A student who made one dive to 20 feet for less than 20 minutes used a half tank of air and later told me that he started to feel awkward as if he were stoned. Was he experiencing nitrogen narcosis?

At a depth of 20 feet the partial pressure of nitrogen is not elevated to the levels that cause nitrogen narcosis, the effects of which usually appear at a depth of at least 100 feet (33 meters) but sometimes can occur in somewhat shallower water.

A variety of things — such as dive gear, underlying medical conditions, psychological conditions, or drugs and medications — could cause your student’s experience, but we need more details to provide a proper explanation. His gas consumption may indicate hyperventilation occurred during the dive.

Without further speculation, the student will need a dive medical exam, and he should discuss this incident with a dive medical physician if he wishes to pursue training. If the physician finds no psychological or medical contraindications, instructors should initially conduct his dive training slowly and with close observation to ensure no recurrence.

— Robert Soncini, NR-P, DMT

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2020