When you think of a billfish, what comes to mind? Perhaps it’s a swordfish, a sailfish, or even the giant marlin from Ernest Hemingway’s classic The Old Man and the Sea. It can be confusing because 12 species are collectively known as billfish: one swordfish, four spearfish, two sailfish, and five marlins.

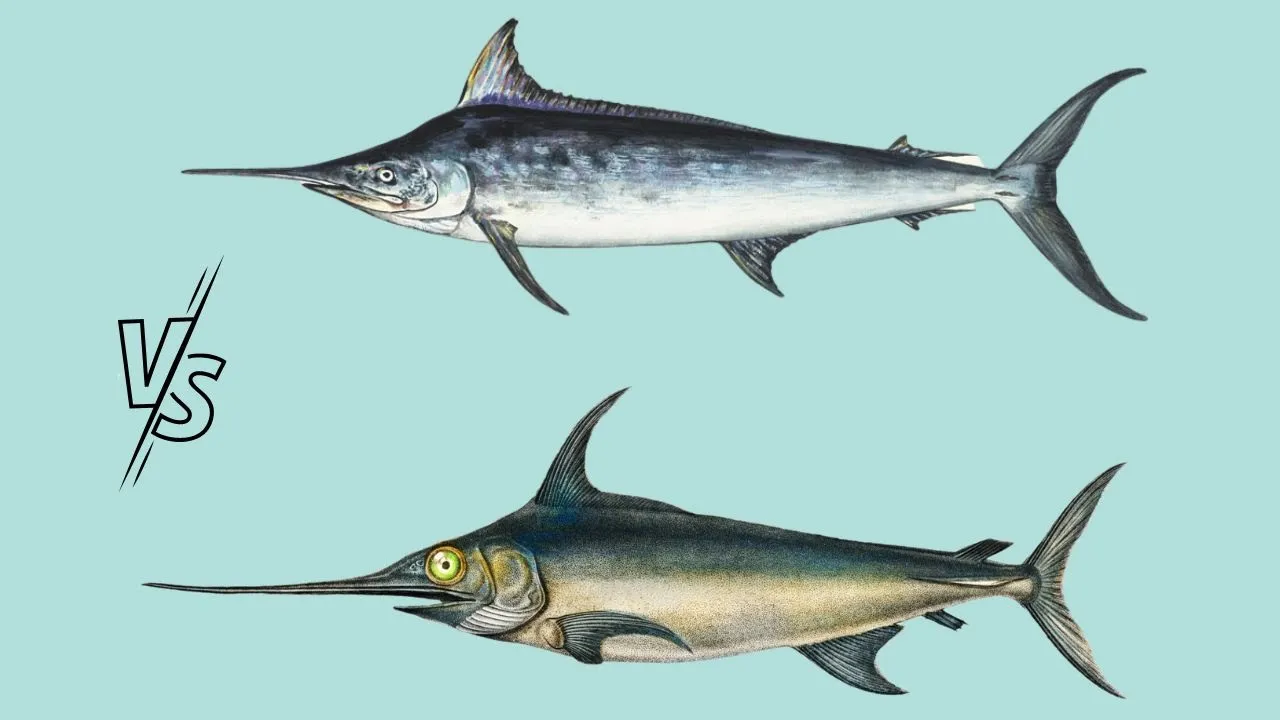

Some immediate differences between the species are in body size and the shape of their sails. The swordfish is notable for its size, reaching up to 1,200 pounds (680 kilograms) and 14 feet (4.3 meters) long. It is classified in a distinct taxonomic family, and its bill differs from a marlin’s.

The four species of spearfish are generally smaller than marlins, and we don’t know much about them.

There continues to be some taxonomic disagreement on whether there are one or two species of sailfish. They are easily recognizable by their large sails, which unfurl during feeding and act as a mechanism for cooling. The Indo-Pacific sailfish is renowned as the fastest fish in the ocean, capable of swimming in short bursts at speeds around 68 mph (109 kph).

Billfish are incredibly fast due to their highly forked tails, which provide powerful thrust, and their streamlined bodies with pectoral fins swept back (although black marlins cannot fold their fins against their bodies). They possess white muscle fibers that generate high energy, contributing to their speed.

The five marlin species are a diverse group that display significant differences in body size, and fishers prize them for their incredible fight and spectacular jumps. The black marlin holds the record for the largest weight at 1,560 pounds (708 kg). The two species of blue marlin — Atlantic and Indo-Pacific — reach up to 1,402 pounds (636 kg). The striped marlin, known for its pronounced stripes, often weighs more than 450 pounds (204 kg), and the white marlin weighs around 180 pounds (82 kg).

Each species possesses unique traits and adaptations. Billfish are found worldwide in the open ocean and are highly migratory, with species-specific ranges and temperature preferences. Females are typically larger than males and are solitary, except during feeding events and reproduction (spawning). Spawning often occurs in pairs, unlike many fish species that spawn in large groups.

Billfish have a long evolutionary history, with the earliest species appearing around 55 million years ago. Modern billfish, which include marlin species, emerged about 17 million years ago. Ancient billfish had bills of equal length, but today’s billfish have evolved a projection of only the upper jaw, which they use to slash left and right to cut and stun schools of fish. The billfish then swim through the stunned fish to consume their prey headfirst.

The aptly named swordfish has a bill shaped like a sword, while the bills of marlins are more spear-like. Predators of marlins include great white and mako sharks, which have often been found with marlin spears embedded in their bodies as evidence of their deadly encounters.

In addition to their physical adaptations, marlins have an extraordinary ability to superheat their brains and eyes above the ambient water temperature. This unique trait gives them a significant advantage in controlling their physiology and enhances the speed of their vision. Their eyes can effortlessly track fast-moving prey. They possess color vision due to a particular arrangement of rods with both single and double cones in the retina. This combination of fast eyes and color vision enables them to effectively spot and pursue prey, even at great depths.

Marlins and other billfish often hunt cooperatively in groups, displaying spectacular flashes of colors on the sides of their bodies during their pursuit of prey. These flashes result from chemical reactions involving melanophores and reflective crystal structures in their skin cells. Imagine a cover over a small mirror; when the cover is removed, the crystal mirrors reflect dazzling light, creating flashes we can see.

Researchers initially believed these flashing stripes disoriented prey fish congregated in large baitballs. The eyes of mackerels and sardines are fine-tuned to detect the color flashes of striped marlins during attacks. New research using drones, however, suggests that this behavior is more complex. As pairs of striped marlins approach a bait ball, they remain dull until the lead marlin gets close and brightly flashes while maneuvering for the attack. The secondary marlin stays dull until it becomes the leader, and then it proceeds to flash as it attacks. The new interpretation is that the flash not only disorients prey but also signals to other marlins to avoid attacking. This mechanism helps them avoid injuring each other during high-speed chases for prey.

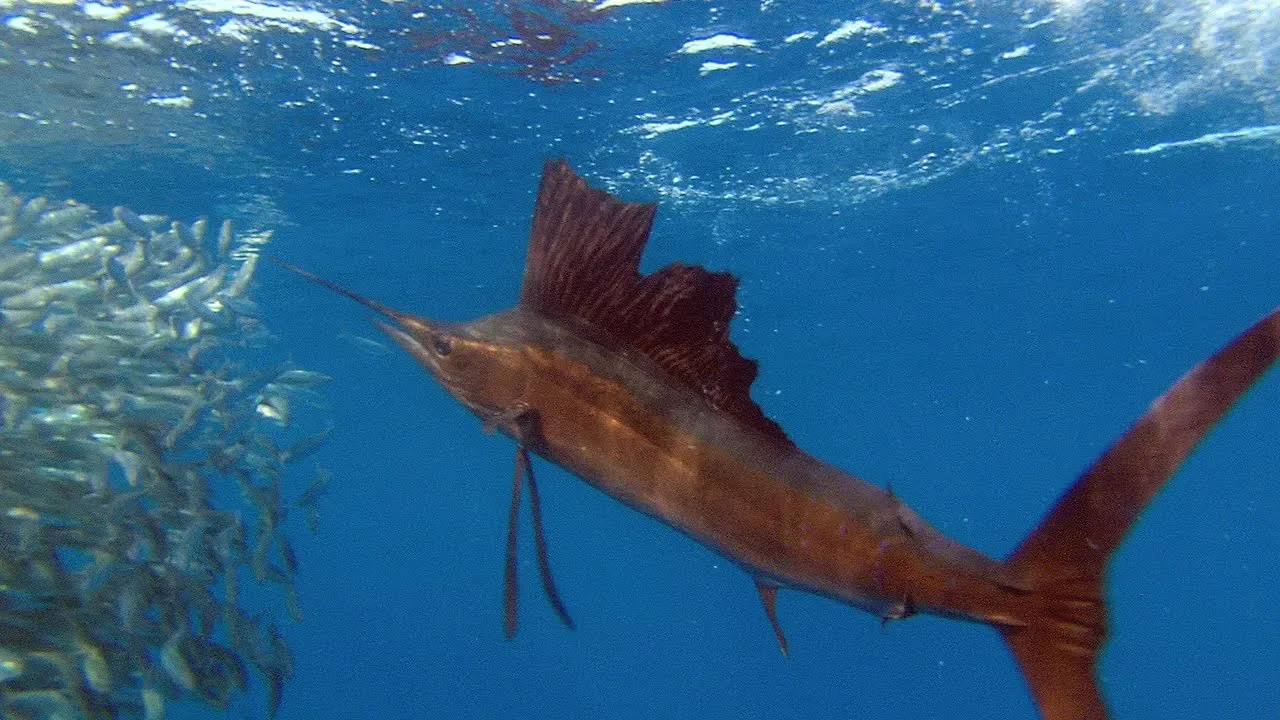

It is exhilarating to witness this behavior while underwater, which you can do in the warm, crystal-clear Caribbean waters off the coast of Cancun near Isla Mujeres, Mexico. You can snorkel alongside sailfish as they brightly flash their colors and unfurl their large, majestic sails. From January through March, these sailfish follow their migrating prey and make explosive attacks on the baitballs.

Boat captains locate the sailfish by following frigate birds trailing above and opportunistically feeding on the sardine runs. Once the captain finds the sailfish feeding on the baitballs, you can descend into the water to observe the phenomenon. The heart-pounding action offers an unparalleled opportunity for video and photography.

From October to December you can visit Magdalena Bay off the Pacific coast of Baja California, Mexico, to snorkel with striped marlins as they feed on baitballs offshore. This event has been a favorite among adventurous tourists and professional filmmakers for years. The chance to snorkel with striped marlins is incomparable. The flashing colors, the maneuvers, the speed, the precision, and the power are truly mind-bending to witness.

During this spectacle, marlins push the baitball toward the surface, where diving birds attack it. California sea lions may also join in the action. New research has recorded more than 5,000 attacks by sea lions on baitballs, revealing that sea lions often steal fish immediately after the marlins strike with their bills. These clever and bold thieves engage in kleptoparasitism, which reduces the frequency of marlin attacks on bait and creates interference competition.

Expedition operators have employed former fishers as ecotourism guides. The idea behind this initiative is straightforward. In the nearby Cabo San Lucas area, fishing generates $50 million to $70 million annually for the local economy. The ecotourism industry is based on the notion that noninvasive nature tours will help maintain populations of marlins and other species, thereby ensuring future income and preserving these species for future generations.

Ecotours bring value to nature and help maintain local biodiversity — a win for everyone if done correctly. Tour operators who take snorkelers to swim with striped marlin sometimes directly compete with high-end fishing charters for access, creating conflicts. Studies show, however, that mortality rates for catch-and-release fishing of marlin are relatively low. Marlins recover from being captured within five to nine hours after release. Marlin sportfishing can be sustainable if done with care, such as using circle hooks instead of J hooks and minimizing fight times and fish time out of the water.

Commercial and industrial longliners targeting tuna and swordfish are the primary drivers of marlin mortality across all species. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) classifies the risk to white and striped marlin as Least Concern (not qualifying for Critically Endangered, Endangered, Near Threatened, or Vulnerable), blue marlin as Vulnerable, and black marlin as Data Deficient (meaning a lack of data). Engaging the sportfishing community offers an unprecedented opportunity to learn more about these incredible fish. Fishers can tag marlins to help us understand their migrations and identify possible spawning areas.

Scientists are participating in striped marlin snorkeling expeditions in Magdalena Bay, searching for marlin larvae and tracing them to spawning grounds to determine areas that need special protection. These efforts are opportunities for citizen scientists and all who use billfish as resources to support sustainable ecotourism and promote conservation, ensuring that these animals not only survive into the future but also thrive.

Explore More

Learn more about billfish in these videos.

© Alert Diver – Q3 2024