The term arrhythmia (or, sometimes, dysrhythmia) means an abnormal heartbeat. It is used to describe a number of very well defined electrophysiological manifestations ranging from benign, harmless conditions to severe, life-threatening disturbances of the heart’s rhythm.

The heart’s electrical wiring is one of the most sophisticated and enduring pieces of nature’s engineering. It controls the rate at which your heart has been beating, every minute, hour and day, 365 days a year since before you were born. Such a precise function on such a vital organ, disease or damage to that wiring can cause symptoms and increase the risk of premature death.

Divers should be aware of its potential implications in diving; and any physicians who treat them should be familiar with their effects on the safety of scuba divers.

Symptoms

A normal heart beats between 60 to 100 times per minute. In well-trained athletes, or even some non-athletic individuals, a heart at rest may beat at as slowly as 40 to 50 times a minute. Entirely healthy, normal individuals experience occasional irregular isolated heart beats or minor changes in their heart’s rhythm. These isolated extra heart beats can be caused by drugs (such as caffeine), or stress, or can occur for no apparent reason.

Dysrhythmias become serious only when they are prolonged or when they do not result in proper and effective contraction of the heart. Physiologically significant extra heartbeats (also known as extrasystoles) may originate in the upper chambers of the heart (this is called supraventricular tachycardia) or in the lower chambers of the heart (this is called ventricular tachycardia). The cause of these extra beats may be a short circuit, an additional parallel conduction pathway in the heart’s wiring, or it may be the result of some other more complex cardiac disorder. People who have episodes or periods of rapid heartbeat are at risk of losing consciousness during such events. Other people have a fairly stable dysrhythmia (such as fixed atrial fibrillation) but in conjunction with additional cardiovascular disorders or other health problems that may exacerbate the effect of their rhythm disturbance. An abnormally slow heartbeat (or a heart blockage) may cause symptoms as well as concerns.

Implications in Diving

The risk for any person who develops a dysrhythmia during a dive is loss of consciousness; which exposes the diver to leading to an unacceptably high risk of drowning. Serious dysrhythmias, such as ventricular tachycardia (VT) and many types of atrial dysrhythmias, are incompatible with diving. Supraventricular tachycardia, for example, is unpredictable in its onset and may even be triggered simply by immersing one’s face in cold water. Anyone who has had more than one episode of this type of dysrhythmia should not dive.

Most dysrhythmias that require medication to be controlled often disqualify the affected individual from safe diving. Exceptions may be made on a case-by-case basis in consultation with a cardiologist and a diving medical officer.

An individual who has any cardiac dysrhythmia needs a complete medical evaluation by a cardiologist prior to engaging in any diving activities.

Electrophysiology studies (EPS) can often identify abnormal conduction pathways, and in some cases the problem can be corrected. Recently, clinicians and researchers have determined that people with some dysrhythmias (such as certain types of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome, which is characterized by an extra electrical pathway) may safely participate in diving after a thorough evaluation by a cardiologist. Also in select cases, people with stable atrial dysrhythmias (such as uncomplicated atrial fibrillation) may dive safely if a cardiologist determines that they have no other significant health problems.

Common Dysrhythmias & Impacts on Diving

Atrial Fibrillation

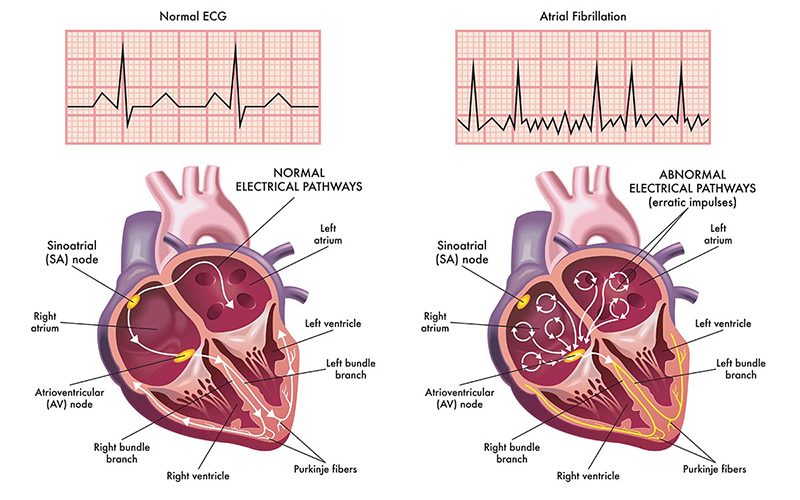

Atrial fibrillation (AF, or also known simply as AFib) is the most common form of dysrhythmia, and it is characterized by an irregular and fast heartbeat.

AF results from a disturbance of the electrical signals that normally make the heart contract in a controlled rhythm, where one can easily predict when the next heart beat will come. During an AFib, the heart’s rhythm is chaotic, and rapid impulses cause an uncoordinated atrial filling and ventricle pumping action. This leads to a decrease in overall cardiac output, which can affect one’s exercise capacity or even result in unconsciousness. In addition, AF causes blood to pool in the atria. Blood pooling promotes the formation of clots, which can break loose and enter the circulatory system. This increase the risk of a stroke, as any of these lose clots could easily impacts the brain an cause infarction.

The most common causes of AF are hypertension and coronary artery disease. Additional causes include a history of valvular disorders, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (a thickening of the heart’s muscle), deep vein thrombosis (DVT), pulmonary embolism, obesity, hyperthyroidism, heavy alcohol consumption, an imbalance of electrolytes in the blood, cardiac surgery and heart failure.

Some people with AF experience no symptoms and are unaware they have the condition until it’s discovered during a physical examination. Others may experience symptoms such as the following:

- Palpitations (a racing, uncomfortable, irregular heartbeat or a flip-flopping sensation in the chest)

- Weakness

- Reduced ability to exercise

- Fatigue

- Lightheadedness

- Dizziness

- Confusion

- Shortness of breath

- Chest pain

The occurrence and duration of atrial fibrillation usually falls into one of three patterns:

- Occasional (or paroxysmal): The rhythm disturbance and its symptoms come and go, lasting for a few minutes to a few hours, and then stop on their own. Such events may occur a couple of times a year, and their frequency typically increases over time.

- Persistent: The heart’s rhythm doesn’t go back to normal on its own, and treatment — such as an electrical shock or medication — is required to restore a normal rhythm.

- Permanent: The heart’s rhythm can’t be restored to normal. Treatment may be required to control the heart rate, and medication may be prescribed to prevent the formation of blood clots.

Any new case of AF should be investigated and its cause determined. An investigation may include a physical exam; an electrocardiogram; a measurement of electrolyte levels, including magnesium; a thyroid-hormone test; an echocardiogram; a complete blood count; and/or a chest X-ray.

Treating the underlying cause of AF can help control the fibrillation. Various medications, including beta blockers, may help regulate the heart rate. A procedure known as cardioversion — which can be performed with either a mild electrical shock or medication — may prompt the heart to revert to a normal rhythm; before cardioversion is attempted, it is essential to ensure that a clot has not formed in the atrium. Cardiac ablation may also be used to treat AF. In addition, anticoagulant drugs are often prescribed for individuals with AF to prevent the formation clots and thus reduce their risk of stroke. It is also of note that the neurological effects of an embolic stroke associated with AF can sometimes be confused with the symptoms of decompression sickness.

Implications in Diving: A thorough medical examination should be conducted to identify the underlying cause of the atrial fibrillation. It is often the underlying cause that is of most concern regarding fitness to dive. But even atrial fibrillation itself can have a significant impact on cardiac output and therefore on maximum exercise capacity. Individuals who experience recurrent episodes of symptomatic AF should refrain from further diving. The medications often used to control atrial fibrillation can present their own problems, by causing other dysrhythmias and/or impairing the individual’s exercise capacity. It is essential that anyone diagnosed with AF have a detailed discussion with a cardiologist before resuming diving.

Extrasystoles

Heart beats that occur outside the heart’s regular rhythm are known as extrasystoles. They often arise in the ventricles, in which case they are referred to as premature ventricular contractions or sometimes premature ventricular complexes, abbreviated as PVCs. The cause of such extra beats is often benign, but it can also result from serious underlying heart disease.

PVCs are common even in healthy individuals; they have been recorded in 75 percent of those who undergo prolonged cardiac monitoring (for at least 24 hours, that is). The incidence of PVCs also increases with age; they have been recorded in more than 5 percent of individuals more than 40 years old who undergo an electrocardiogram (or ECG, a test that typically takes less than 10 minutes to administer). Men seem to be affected more than women.

The extrasystole itself is usually not felt. It is followed by a pause — a skipped beat — as the heart’s electrical system resets itself. The contraction following the pause is usually more forceful than normal, and this beat is frequently perceived as a palpitation — an unusually rapid or intense beat. If extrasystoles are either sustained or combined with other rhythm abnormalities, affected individuals may also experience dizziness or lightheadedness. Heart palpitations and the sensation of missed or skipped beats are the most common complaints of those who seek medical care for extrasystole.

A medical examination of the condition begins with a history and physical, and should also include an ECG and various laboratory tests, including the levels of electrolytes (such as sodium, potassium and chloride) in the blood. In some cases, doctors may recommend an echocardiogram (an ultrasound examination of the heart), a stress test and/or the use of a Holter monitor (a device that records the heart’s electrical activity continuously for a 24- to 48-hour period). Holter monitoring may uncover PVCs that are unifocal — that is, they originate from a single location. Of greater concern are multifocal PVCs — those that arise from multiple locations — as well as those that exhibit specific patterns known R-on-T phenomenon, bigeminy and trigeminy.

If serious structural disorders, such as coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathy (a weakening of the heart muscle), can be ruled out — and the patient remains asymptomatic — the only “treatment” required may be reassurance. But for symptomatic patients, the course is less clear, as there is controversy regarding the effectiveness of the available treatment options. Two drugs commonly used to treat high blood pressure — beta blockers and calcium channel blockers — have been used in patients with extrasystole with some success. Antiarrhythmics have also been prescribed for extrasystole but have met with mixed reviews. A procedure known as cardiac ablation may be an option for symptomatic patients, if the location where their extra beats arise can be identified; the procedure involves threading tiny electrodes into the heart via catheters, then zapping the affected locations to rewire the heart’s faulty circuits.

Implications in Diving: Although PVCs are present in a large percentage of otherwise normal individuals, they have been shown to increase mortality over time. If PVCs are detected, it is important that they be investigated and that known associated conditions be ruled out. Divers who experience PVCs and who are found to also have coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathy will put themselves at significant risk if they continue to dive. Divers diagnosed with R-on-T phenomenon, nonsustained runs of ventricular tachycardia or multifocal PVCs should likewise refrain from diving. Divers who experience PVCs but remain asymptomatic may be able to consider a return to diving; such individuals should discuss with their cardiologist their medical findings, their desire to continue diving and their clear understanding of the risks involved.