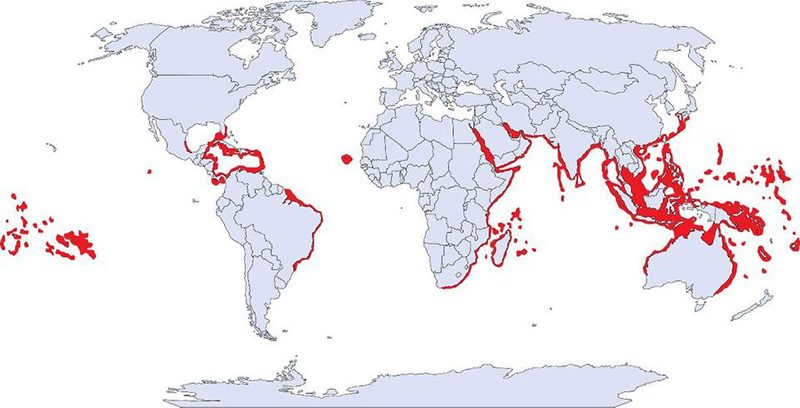

Fire corals are colonial marine cnidarians that can cause burning skin reactions. Fire-coral-related incidents are common among divers, especially those with poor buoyancy control. They belong to the genus Millepora and live in tropical and subtropical waters around the world.

Fire corals usually have a yellow-green or brownish, branching formation. Their external appearance will often vary depending on the substrate they grow on or environmental factors such as currents. They can colonize hard structures (dead corals and gorgonians, rocks, metal objects, plastic and other trash) and sometimes appear stony. Despite their characteristic calcareous structure, fire corals are not true corals. They are hydrozoans, which means these animals are more closely related to the Portuguese man-of-war and other stinging hydroids than to calcareous corals.

Mechanisms of Injury

Fire corals get their name because of the fiery sensation experienced after coming into contact with them. The mild to moderate burning that they cause is the result of cnidocytes embedded in their calcareous skeleton. These cnidocytes contain nematocysts that will release when touched, injecting their venom.

Signs and Symptoms

Contact causes a burning sensation that may last several hours. There is often a skin rash, which tends to appear minutes to hours after contact. Depending on the individual’s susceptibility and the localization of the injury, the skin rash may take several days to resolve. Often, the skin reaction will subside in a day or two, but it may reappear several days or weeks after the initial rash disappears. Fire-coral lacerations, in which an open wound receives internal envenomation, are the most problematic fire-coral injuries. Venom from Millepora spp. is known to cause tissue necrosis on the edges of a wound. Carefully monitor these injuries, as necrotic tissue provides a perfect environment to culture serious soft tissue infections.

Prevention

- Avoid touching fire coral formations.

- If you need to kneel on the bottom, look for clear, sandy areas.

- Remember that fire corals may colonize hard surfaces such as rocks and old conchs, which may not look branchy.

- Always wear full-body wetsuits to provide some protection against the effects of contact.

- Master buoyancy control.

- Always look down while descending.

First Aid

- Rinse the affected area with white household vinegar. White household vinegar (or a mild acetic acid solution of 2 to 5 percent in water) tends to stabilize unfired nematocysts. Vinegar will not do anything to injected venom. It only prevents further envenomation from unfired nematocysts.

- Redness and blisters will likely develop regardless of any timely first aid treatment. Do not puncture these blisters; just let them dry out naturally.

- Keep the area clean, dry and aerated — time will likely do the rest.

- For open wounds, seek medical evaluation. Fire coral venom is known to have dermonecrotic (tissue death) effects. Share this information with your physician before any attempts to suture an open wound, as the wound edges might become necrotic.

- Antibiotics and a tetanus booster may be necessary.

- These injuries tend to relapse after a week or two of what seemed to be a proper resolution. Relapse is normal.

Implications in Diving

For the Diver

- Follow the first aid recommendations above.

- Seek professional medical evaluation. Any doctor should be able to help, regardless of any dive medicine knowledge or training.

For the Dive Operator

- Provide first aid treatment, as described above. As the expedition’s leader, you have a duty of care for a diver injured during your trip.

- Be skeptical of folkloric first aid treatments. Use common sense, and don’t attempt magic solutions. Remember that you might be liable.

- Get the diver evaluated by a medical professional.

- Don’t worry about finding a doctor with dive medicine experience. Any doctor should be able to help with the initial evaluation.

For the Physician

- Treatment is usually symptomatic (anti-inflammatory drugs, antihistamines, antibiotics for lacerations and open wounds).

- For open wounds requiring stitches, remember this venom is dermonecrotic. Although it might be tempting to stitch together close, cleaned edges, these might become necrotic. Consider healing by secondary intention.

- Antibiotics and a tetanus booster may be necessary.

- Protect wounds from the sun, as scars might leave a hyper- or hypopigmented area.

Fitness to Dive

You can consider a return to diving if a physician determines that the injury is closed and there are no unacceptable risks of infection.