Sea urchins are typically small, round, spiny creatures found on shallow, rocky marine coastlines. The primary hazard associated with sea urchins is contact with their spines.

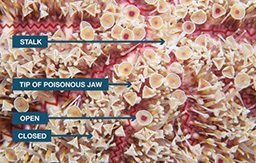

Sea urchins are echinoderms, a phylum of marine animals that also includes starfish, sand dollars and sea cucumbers. Echinoderms are recognizable because of their pentaradial symmetry (they have five rays of symmetry), which is easily observed in starfish. This symmetry corresponds with a water vascular system used for locomotion, transportation of nutrients and waste, and respiration. Sea urchins have tubular feet called pedicellariae, which enable movement. In one genus of sea urchin — the flower sea urchin — some of the pedicellariae have evolved into toxic claws. In these animals, the spines are short and harmless, but these toxic claws can inflict an envenomation.

Sea urchins feed on organic matter in the seabed. Their mouth is located at the base of their shell, and their anus is on the top. Sea urchins’ color varies by species — shades of black, red, brown, green, yellow and pink are common.

There are species of sea urchins in all oceans, from tropical to arctic waters. Most incidents between humans and sea urchins occur in tropical and subtropical waters. The flower sea urchin (Toxopneustes spp.) is the most toxic of all sea urchins. Its short spines are harmless, but its pedicellariae, which look like small flowers, are tiny claws (Toxopnueustes means “toxic foot”). These claws contain a toxin that can cause severe pain and other symptoms similar to those of a jellyfish sting.

Mechanism of Injury

Sea urchins are covered in spines, which can easily penetrate divers’ boots and wetsuits, puncture the skin and break off. These spines are made of calcium carbonate, the same material that makes up eggshells. Sea urchin spines are usually hollow and can be fragile, particularly when the time comes to extract broken spines from the skin.

Injuries usually happen when people step on urchins while walking across shallow rocky bottoms or tide pools. Divers and snorkelers are often injured while swimming on the surface in shallow water, as well as when entering or exiting the water from shore dives.

Although little epidemiological data is available, sea urchin puncture wounds are common among divers, particularly when in shallow waters, near rocky shores or close to wrecks or other hard surfaces.

Signs and Symptoms

Injuries generally take the form of puncture wounds, often multiple and localized. Skin scrapes and lacerations are also possible. Puncture wounds are typically painful and associated with redness and swelling. Pain ranges from mild to severe depending on several factors, including the species of sea urchin, the location of the wound on the body, whether joints or deeper muscle tissues are involved, number of punctures, depth of puncture and the individual’s pain tolerance. Multiple puncture wounds may cause limb weakness or paralysis, particularly with the long-spined species of the genus Diadema. On very rare occasions, immediate life-threatening complications may occur.

Prevention

- Be observant while entering or exiting the water from shore dives, particularly when the bottom is rocky.

- If swimming, snorkeling or diving in shallow water, near a rocky shore or close to wrecks or other hard surfaces, maintain a prudent distance and good buoyancy control.

- Avoid handling these animals.

First Aid

There is no universally accepted treatment for sea urchin puncture wounds. Both first aid and definitive care are symptomatic.

- Apply heat. Immerse the affected area in hot water (no hotter than 113°F/45°C) for 30 to 90 minutes. If you are assisting a sting victim, first test the water yourself to assess heat. Do not rely on the victim’s assessment, as pain may impair their ability to evaluate heat. If you cannot measure the water temperature, a good rule of thumb is to use the hottest water you can tolerate without scalding. Different body areas have different tolerance to heat, so test the water on yourself on the same area where the diver was injured. Repeat if necessary.

- Very few species of sea urchins contain venom. If venom is present, hot-water immersion may also help denature any superficial toxins.

- Remove any superficial spines. Tweezers can be used for this purpose, but sea urchin spines are hollow and can be very fragile when grabbed from the sides. Your bare fingers are a softer alternative to tweezers.

- Do not attempt to remove spines embedded deep in the skin; let medical professionals handle those. Deeply embedded spines may break down into smaller pieces, complicating the removal process.

- Wash the area thoroughly, but avoid forceful rubbing and scrubbing if you suspect there may still be spines embedded in the skin.

- Apply an antiseptic or over-the-counter antibiotic ointment if available.

- Do not close the wound with tape or glue; this might increase the risk of infection.

- Deep puncture wounds are the perfect environment to culture an infection, particularly tetanus.

Regardless of any first aid provided, always seek a professional medical evaluation.

Implications in Diving

For the Diver

- Seek a professional medical evaluation as soon as reasonably possible. Do not neglect these wounds.

- Don’t worry about finding a doctor with dive medicine experience; any doctor should be able to help.

- Puncture wounds in the vicinity of a joint can be problematic.

- Do not neglect these wounds, some of the complications could have a negative impact for life.

For the Dive Operator

- As the leader of the expedition, you have a duty of care if the injured party was injured during your trip.

- Provide first aid treatment as descried above.

- There are many folkloric first aid treatments proposed for sea urchin puncture wounds; use common sense, and refrain from attempting any scientifically unsound solutions. Remember, you might be liable.

- Have the customer evaluated by a medical professional — any doctor should be able to help.

For the Physician

- There is no universally accepted treatment. For the most part, treatment is symptomatic.

- Very few species of sea urchins are actually toxic.

- Antigens present on the teguments covering the spines could be causing swelling.

- The decision of whether surgical removal of retained spines is necessary is usually based on joint or muscular layer involvement and whether there is pain with movement or signs of infection.

- Remaining spines will usually encapsulate in a short time, but they may not always dissolve.

- Although these wounds don’t always get infected, it is worth considering prophylactic antibiotic therapy.

- Make sure your patient has adequate immunization for tetanus. Deep puncture wounds are potentially tetanogenic.

- Reassess frequently over the first few days to monitor progress and possible infection.

For additional information about marine life injuries, check out the Hazardous Marine Life Medical Reference Book.