Sinus barotraumas are among the most common diving injuries. When the paranasal sinuses fail to equalize to barometric changes during vertical travel, damage to the sinus can cause sharp facial pain with postnasal drip or a nosebleed after surfacing. Although sinus barotrauma is a prevalent and generally benign diving injury, some of its complications could pose a significant risk to the diver’s health. Divers should never underestimate difficulties equalizing sinuses.

Anatomy and Functions of the Paranasal Sinuses

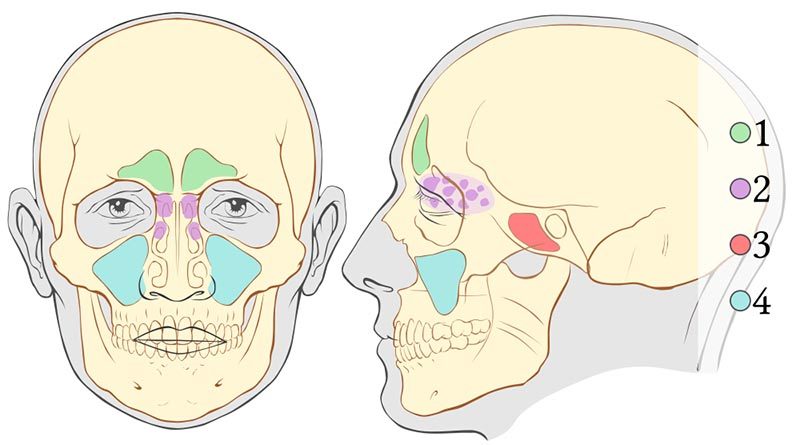

The paranasal sinuses are gas-filled cavities in your facial bones and skull. They have several functions: They lighten the weight of your head, play a significant role in the resonance of your voice, serve as collapsible structures that protect vital organs during facial trauma, and may help the turbinates (small structures inside the nose) humidify and heat the air we breathe. There are two sets of four sinus cavities, one set on the right and one on the left.

- The frontal sinuses (area one) are located within the forehead above your nose and eyes and are surrounded by thick, bony walls.

- The ethmoid cells (area two) are located within the ethmoid bone between your eyes and nose and are formed by a variable number of connected individual cells.

- The sphenoidal sinuses (area three) are centrally located behind the nasal cavity and vary in size and shape.

- The maxillary sinuses (area four) are located within the maxillary bone below your eyes and lateral to your nose and are the largest pair of paranasal sinuses.

The paranasal sinuses communicate with the nasal cavity via small orifices called ostia (singular: ostium). The ostia can easily be blocked by inflammatory processes, like colds or allergies, and in divers by improper attempts at equalization. Ostia blockage can impair drainage and make both descents and ascents troublesome.

Mechanisms of Injury

Every foot of descent in water adds approximately one-half pound of pressure on each square inch of tissue. The pressure diminishes by the same amount on ascent. According to Boyle’s Law, as the ambient pressure increases while descending, the volume of the gas in an enclosed space decreases proportionately. As the ambient pressure decreases while ascending, the volume of the gas increases proportionately.

While descending, it is imperative that divers actively or passively equalize all enclosed air-filled spaces to avoid injury. While ascending, the increasing volume usually vents itself passively.

The mechanisms of injury of sinus barotraumas depend on whether it happened during descent or ascent.

During Descent (Squeeze)

Failure to equalize pressures on paranasal sinuses while descending keeps these cavities at atmospheric pressure, which results in a relative negative pressure (vacuum) as you descend to depth. The first sign of this type of sinus barotrauma is generally a sharp pain. The capillary vessels of the mucous membranes lining the sinuses engorge and burst, likely filling the sinuses with blood until the negative pressure is equalized. At this point the pain usually resolves or diminishes, and the diver continues the dive. While ascending, any remaining gas within the sinus expands and forces out this blood and mucus. These barotraumas usually manifest as postnasal drip or bloody discharge from the nose, depending on the sinuses involved. The bleeding can increase if you are taking blood thinners that include aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

During Ascent (Reverse Block)

Sinus barotrauma can also happen during ascent, known as a reverse block. Equalization of ears and sinuses during ascent is usually a passive event, which means active attempts should not be necessary. However, mild swelling and inflammation of the mucous membranes (as caused by a cold or by seasonal allergies) can compromise the narrow passages through which air escapes, trapping gas, mucus and blood. If a sinus fails to vent during ascent, the increasing pressure can apply significant tension to the mucosal lining and bony walls of the sinus. As the diver continues to ascend, one of the sinus walls can burst into an adjacent sinus that did vent correctly (the point of least resistance), effectively relieving the excess pressure. This type of sinus barotrauma manifests as a sharp facial pain during ascent, followed by a nosebleed or postnasal drip depending upon the sinus cavities involved.

Manifestations

The most common manifestations of sinus barotrauma are sharp facial pain during descent or ascent and blood dripping from the nose after surfacing. It is not uncommon for sinus barotrauma to be painless and manifest only as bloody mucus in the mask or the back of the throat.

Signs and Symptoms

Pain

- Pain is usually facial in the region corresponding to the compromised sinus. In most cases the pain has a direct relation with changes in pressure on descent or ascent. In some cases the pain is delayed for a few hours; for example, when a sinus remains slightly over-pressurized following a dive.

- Sharp pain in your forehead above and between the eyebrows is often a sign of barotrauma to your frontal sinuses. It is often described as an “ice-cream headache.” This type of sinus barotrauma usually has a direct relationship with changes in depth.

- Pain behind your eyes is usually the result of a compromise to the ethmoidal sinus. You may also experience sharp pain, associated with changes in depth, behind and above the eyes.

- Sharp pain beside your nose and below your eyes (upper maxillary region) is often a sign of maxillary sinus barotrauma. With changes in depth the pain might radiate to the upper molars or gums on the same side as the facial pain. The maxillary sinus and the upper jaw are supplied by the same nerve (trigeminal nerve).

- Pain in the back (occipital region) or top of the head is the most intriguing, as its connection with the deeper sphenoidal cells is not obvious. When compared to the other sinuses, pain in the occipital region is often duller, like a normal headache. The association with changes in depth should be a clue that leads to a sinus origin.

Bleeding

- You may notice some blood mixed with mucus and saliva in your mask after surfacing. You might not have been aware of it while diving. Minor bleeding that drips from the nose (technically not a nosebleed) or from the nose to the throat is typical of sinus barotrauma.

- Minor bleeding is seldom a severe problem, but if you take an anticoagulant medication, be cautious when diving in a remote location. Uncontrolled bleeding without timely access to a medical facility prepared for such emergencies could be a severe health threat.

Coughing or Spitting Up Blood

While a nosebleed is not usually a manifestation of a life-threatening condition, postnasal drip usually results in blood in the diver’s mouth. This might be disconcerting to divers as it could be interpreted as the diver coughing up or spitting up blood. While there may be clues to determine whether this bloody discharge is of pulmonary origin or the result of sinus barotrauma, it is beyond the scope of what someone without medical training should attempt to evaluate. When in doubt, seek medical evaluation immediately.

Prevention

- Do not dive when congested.

- Refrain from diving when feeling fullness, pressure or pain in your paranasal sinuses.

- Learn and use proper equalization techniques.

Medications

Talk to your doctor if you feel you need medication to dive. An ENT doctor is ideal for both ear and sinus problems, but your primary care physician can help with common problems. Using nasal sprays containing antihistamines and decongestants before diving may reduce swelling in the nasal and ear passages. Some are prescription only, while some are over the counter (OTC). With either option, your doctor may have special instructions on how to use them while diving.

Antihistamines prevent the effects of histamine, a substance produced and released by your body during the inflammations that cause nasal congestion, swelling of the mucous lining, and sneezing. While some of these drugs may cause drowsiness, second-generation antihistamines like cetirizine, loratadine and fexofenadine do not.

Decongestants relieve symptoms caused by the already-released histamine, clearing nasal and sinus congestion. Decongestants are not suitable for use by everyone. Some cardiovascular and central nervous system side effects could be concerns while diving.

Most nasal sprays work best if used one to two hours before the descent. They last from eight to 12 hours, so there is no need to take a second dose before a repetitive dive. Take short-acting nasal sprays like oxymetazoline 30 minutes before the descent; these usually last for 12 hours. Repeated use of short-acting OTC sprays can result in a rebound reaction that may set the stage for a reverse block. Steroid nasal sprays do not have this rebound effect but are slow-acting drugs, so you need to start them about a week in advance and use them regularly.

Whether you have a prescription or not, always check with your doctor before attempting to treat any condition.

Risk Factors

If you have a history of sinus trouble, allergies, a broken nose or deviated septum, or you currently have a cold, you may find the clearing procedure challenging to accomplish and may experience a problem with nosebleeds. It’s always best not to dive with a cold or any condition that may block the sinus air passages. If you experience difficulties during descent, this is the time to abort the dive. Remember that you can only abort a descent, never an ascent.

A good way to assess whether your paranasal sinuses are clear is by paying attention to your voice. You will sound like you have a stuffy nose due to a lack of appropriate nasal airflow while speaking.

Being able to breathe through your nose only proves your nasal passages are clear. It does not indicate anything about your paranasal sinuses.

Complications

With this type of injury, blood can run down the back of the throat or pool in the sinuses below the eyes and emerge later (even days after diving) as a thick, black, bloody discharge. The collected blood can also act as a growth medium for bacteria and result in sinus infections.

Pneumocephalus (air between the skull and the brain) and orbital emphysema (air behind and around the eyeball) are rare but important complications of sinus barotraumas. If not adequately treated, they may cause serious neurological and life-threatening complications. Never underestimate sinus barotrauma.

First Aid

- Use a nasal decongestant spray or drops. This might reduce the swelling of the mucous membranes, which may help to open the ostia and drain fluid from the sinuses.

- Seek professional medical evaluation. Any doctor should be able to help, regardless of any dive medicine knowledge or training.

Implications in Diving

For the Diver

- You can consider a return to diving if a physician determines that the injury has healed, and the risk of further injury is no greater than normal.

- Do not neglect these injuries. Some of the complications could negatively affect you for the rest of your life.

For the Dive Operator

- Provide first aid treatment, as described above. As the expedition’s leader, you have a duty of care for a diver injured during your trip.

- Be skeptical of any folkloric first aid treatments. Use common sense, and don’t attempt any magic solutions. Remember that you might be liable.

- Have them evaluated by a medical professional in a timely fashion.

- Don’t worry about referring them to a doctor with dive medicine experience. An ENT specialist is ideal, but any doctor should be able to help.

- Do not allow any further diving once the injury has occurred until they are cleared by a physician.

For the Physician

- Provide symptomatic treatment (anti-inflammatory drugs, decongestants, mucolytic agents).

- Prophylactic antibiotic therapy is controversial. Although a middle-ear infection is a plausible secondary complication, this is not always the case in the acute phase.

- Assess concomitant middle-ear barotrauma.

- If present, consider referring the patient to an ENT specialist.

- Use the O’Neill grading system or detail what you observe.

- Assess the cranial nerve function.

Fitness to Dive

Do not dive until swelling and inflammation have resolved, and you can adequately equalize, preferably under otoscopic evaluation. Assess why the problem occurred (lack of training, allergy, etc.) and address each factor. The inability to equalize properly is disqualifying.

If you are unable to clear your sinuses or you have frequent nosebleeds when diving, you should see your primary care physician or an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist (otolaryngologist) for evaluation.