Office of Naval Research 2014

While vacationing in Croatia, I heard a story about a diver who fits the description of people I sometimes call “robo-divers.” The story’s hero is a famous Croatian sponge diver, with whom I share an acquaintance. My friend, who is one of his teammates, described this robo-diver’s practice, which is similar to previously described empirical dive practices of other local sponge divers: Reportedly, he does four descents per day to extreme depths, after each of which he ascends very slowly without decompression stops. After the last dive of the day, he quickly takes his boat to shallow waters (within approximately 10 minutes) and descends for about two hours of decompression, split between stops at nine, six and three meters (30, 20 and 10 feet).

I don’t know about his decompression sickness history, but I do know that he is 64 years old now, and the fact that he has survived this long following those types of dive practices make me think of him more as a robot than as a man of flesh and bone. At very least, it is unlikely that this diver has a PFO.

None of his teammates follow his dive profile, and I want to emphasize that nobody should try to. For comparison, the U.S. Navy at one point practiced surface oxygen decompression by having divers do in-water decompression stops at up to 12 meters (39 feet) depth before they would ascend to the surface. Within a few minutes after ascent, they would enter a hyperbaric chamber and be recompressed to 12 meters (39 feet) to complete their decompression. Even in this case, with divers partially completing decompression before ascent and adding very short intervals at surface before recompression, the incidence of DCS was relatively high.

Croatia’s robo-diver may actually have something in common with Australia’s pearl divers and Tasmania’s aquaculture divers, although this robo-diver is somewhat more extreme. Wong and Nishi performed empirical tests of pearl divers in the region, helping them to calibrate their dive profiles consisting of multiple descents in succession, punctuated by short surface intervals and followed by decompression stops after the final ascent.

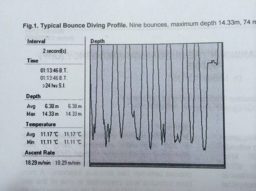

In a recent report at the ONR Project Review meeting, David Smart and co-authors presented the results of their field validation of the “yo-yo” diving schedules of Tasmania’s aquaculture industry. The schedules were developed based on empirical dive practices and scientific control using Doppler techniques to measure circulating venous gas bubbles. Their yo-yo diving tables cover multiple successive descents up to 21 meter (69 feet) depth, with strictly controlled ascent rates and intervals between descents. In a follow-up study, the researchers collected data between 2001-2012 and used Doppler bubble detection as an analysis of decompression stress. The study shows very low bubble grade after such dives, with a DCS incidence rate of 1 per 11,000 dives—far less than previously reported by the same group of divers using “raw” empirical schedules. The incidence of calibrated Tasmania yo-yo diving tables is even lower than in recreational diving. This is an example of how risky empirical diving practices can be improved without interfering with the productivity of divers.

The main safety effect was achieved by keeping surface intervals between descents short, which is contrary to the “rational” approach, and by keeping the ascent rate slow. While empirical diving may sometimes reveal possibilities not yet contemplated by scientists, these empirical practices are risky to try without a systematic approach and adherence to verified schedules.

The Tasmanian bounce diving tables will be published in SPUMS in September 2014.