When I told a nondiving neighbor we were going to the Sunshine Coast in February, his retort was predictable and laced with jealous sarcasm. “Poor thing, must be tough. All that lazing about on the beach, with swaying palm trees and water so warm I bet your rubber diving suits are completely optional.”

When I told my wife, she adopted a pensive look then got right down to business asking, “My suit doesn’t leak anymore, right? I use 40 pounds of lead in my harness? And water temperatures should be mid-40s?” Giving her a triple affirmative with a grin, I then poured on the charm to clinch the deal, adding that the weather forecast was not too terrible and that the tides were actually quite good for shooting the Skook. She half smiled and began creating her packing list: drysuit, “Chewbacca suit” (full-body woolen undergarments), Gore-Tex® rainsuit, plenty of hot cocoa packets, etc. Sunscreen was not on the list.

Trial by Skook

So we come to find ourselves 70 feet down Observation Wall along the west side of the famed Skookumchuck Narrows in British Columbia, our wide eyes feasting on the scenery before us. Countless anemones, sponges, sea stars and sea urchins decorate the wall, a living patchwork quilt of white, yellow, orange, red and purple. Copper rockfish stare curiously back at us, while kelp greenlings glide over the many-hued mosaic. Red Irish lords lounge in lushly carpeted cracks and crevices. Some are cunningly camouflaged, others are easy to spot. To the uninitiated, this vibrant profusion of fins and tube feet, tentacles and spines may seem possible only in the tropical paradise imagined by our neighbor. But those baptized in the Pacific Northwest’s cold waters know better. The emerald-green 45°F sea around us is packed with nutrients that nourish an impressive assemblage of marine life.

The Skook, formally known as Sechelt Rapids, is one of the fastest navigable waterways in North America, and we cannot resist its pull. No one can, actually. The water can shoot through here at 16 knots on a big spring tide, but thankfully we encounter only a whisper of current. Thus we can loiter about and ogle the opulence on display here at one of the Northwest’s best dive sites. We know that this mellow moment is but fleeting. Time and tide wait for no one. All too soon the Skook will be racing, and conditions will be downright dangerous. We are lucky to eke out 15 minutes more before the floodgates open. Lacking the strong five-armed grip of the violet ochre sea star, we are forced to ascend.

Snow and Sunshine

The mix of rain and snow falling from the steel-gray clouds does nothing to cool our enthusiasm as we clamber into the boat. Jabbering through numb lips, we exuberantly recount the dive and soak in the topside view of Sechelt Inlet: steep slopes covered in moss-bearded cedar and fir, tendrils of mist pulled wispy and thin like spun cotton candy, a bald eagle perched imperiously atop a snag. Palm trees and warm breezes are in short supply, but what surrounds us is striking — even idyllic, in a harsh, Vikingesque sort of way. It is much better than some beach on the equator, 3,500 miles to the south.

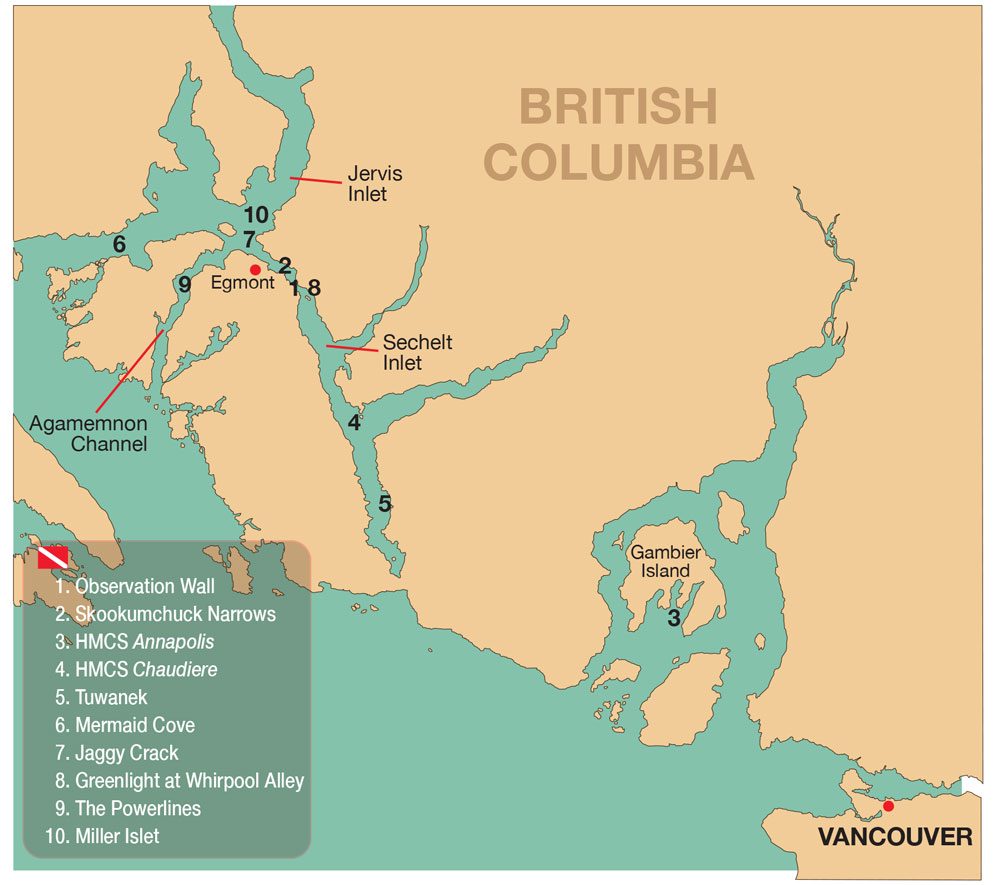

The Sunshine Coast is nestled in the southwest corner of British Columbia (BC), Canada’s westernmost province. Deep fjords cut into majestic mountains, connecting mainland BC with the sea. The Strait of Georgia lies between this 100-mile stretch of rugged, remote coastline and Vancouver Island. To reach the picturesque seaside communities that dot the Sunshine Coast, one must travel by air or ocean. Our midwinter escape to experience the region’s superb diving began by driving from snowbound eastern Washington to Seattle in the western part of the state, heading north across the Canadian border to Vancouver, taking a car ferry to Langdale and finally driving through temperate rainforest up the Sechelt Peninsula to Egmont. Though census takers have not yet calculated the official population of this small town quite literally at the end of the road, Egmont’s location at the intersection of four glacier-carved waterways — Sechelt Inlet, Agamemnon Channel, Hotham Sound and Jervis Inlet — means it is at the center of the Sunshine Coast scuba scene.

Steel in the Deep

BC is widely known for its submerged fleet of seven fabulous shipwrecks and one airplane, all painstakingly prepared and sunk by the Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia. Two of the vessels await divers along the Sunshine Coast. The HMCS Annapolis, BC’s newest wreck, sits upright in 100 feet off Gambier Island, not far from Horseshoe Bay. The HMCS Chaudière — or “the Chaud,” as it is affectionately known by local metalheads — was sunk in 1992 in Sechelt Inlet off Kunechin Point. This destroyer escort measures 366 feet long and rests on its left side in 100 to 140 feet of water, its bow pointed down a steep incline. Surface buoys make the descent simple, but depth and sometimes disorientation (the 90-degree list to port can scramble one’s internal compass) elevate this to an advanced dive.

We begin our tour at 60 feet on the Chaudière’s stern then proceed sharply down the ship’s starboard gunwale to 100 feet. We pass towering orange plumose anemones attached to railings and clusters of glassy tunicates resembling bouquets of transparent flowers. A school of shiner perch darts out of the way, their mirrorlike sides reflecting our light beams, while a lunker of a lingcod lounging on a hatch refuses to budge. Our goal lies deeper still, another atmosphere down. At 130 feet I turn upward to compose my shot, point blank in front of the imposing barrels of the warship’s forward guns. Utterly dwarfed by the massive weaponry, I recite the Chaud’s motto, “Fortune Smiles on the Brave,” to muster up some confidence, and I squeeze my camera’s trigger.

Target-Rich Macro

While the aforementioned wrecks are accessible only by boat, divers with boots on the ground can hit Tuwanek Point in Sechelt Inlets Marine Provincial Park. Popular with Vancouverites — open-water students and seasoned vets alike — a healthy surface swim from this shore site’s easy entry affords access to two small islands just offshore. Beneath the waterline, the islands’ smooth, sloping granite walls are like the broad shoulders of a giant, with clinging boot sponges, feather stars, sea cucumbers and anemones. Gobies and convict fish scoot about, defying Newton, while moon jellies pulse by. Try as we might, we miss the wolf eel and octopus our friends saw a week ago, but we do find a proud papa buffalo sculpin valiantly guarding three clutches of eggs.

At the northern end of the Sunshine Coast, a shore dive in Mermaid Cove near Powell River will give you a glimpse of the Emerald Princess, a 9-foot-tall bronze mermaid statue by Canadian artist Simon Morris, placed at 60 feet in Saltery Bay Provincial Park. Her identical twin sister, Amphitrite, resides in the warmer waters of Grand Cayman.

Leaving our Egmont headquarters in a steady drizzle storm, we set out for a day in Jervis Inlet. With little chance of sun any time soon, I am committed to the pursuit of quality close-up photography. Jaggy Crack is a good place to start. Within minutes I am chasing alabaster nudibranchs and spider crabs while at the same time searching for grunt sculpins among a million feather stars. Pulverized barnacle shell bits on the burgundy-colored rock have me seeing a dusting of new-fallen snow. My wife, Melissa, motions me over to a particularly photogenic crimson anemone, pointing triumphantly under the curtain of its elegant tentacles to where an inch-long candy-stripe shrimp poses. It is one of the coolest critters in these cool waters. I immediately forget everything else on my wish list and go to work shooting the commensal crustacean from every possible angle. I am even successful in ignoring the sea lion that makes a surprise swim-by. A few hours later, nearby Miller Islet delivers more pretty-in-pink crimson anemones, even weirder crabs and a juvenile yelloweye rockfish. After 65 minutes I am feeling the burn of the 45°F water, but it is not enough to make me dream of the tropics. Instead my mind wanders back to the Skook.

Strong-Water Sequel

A compelling reason to visit the Sunshine Coast in the depths of winter (rain or shine) is for the tides, or more specifically, smaller tidal exchanges. Skookumchuck Narrows can be safely dived and enjoyed only on a limited number of days each year. Skookumchuck means “strong water” in the lexicon of the Chinook First Nations people, and you do not want to be underwater when that epic strength manifests. Hundreds of billions of gallons of seawater roar through Sechelt Rapids on each tidal swing, forming whirlpools, boils, downdrafts, standing waves and, yes, rapids. As luck would have it, many of the optimal slack windows — the periods between flood and ebb flows when current is at a minimum and diving at its best — happen to fall when snow blankets the highest peaks of the coastal mountains. Another winter bonus is reduced boat traffic in the Narrows. Visibility also tends to be better. With all these stars properly aligned, we would be crazy not jump back in for another look.

We do just that, choosing Greenlight at Whirlpool Alley on the east side of the Narrows. Slack tide ends up being 20 minutes late. The charts are only predictions after all, so it pays to arrive early and stay late if necessary, all the while remaining at the ready and watching carefully for the current to relent. Different from Observation Wall’s single vertical rock face, Greenlight’s bottomography is a series of shelving fingers that point into the middle of the Narrows. Painted (dahlia) anemones predominate and dazzle the eye with full-spectrum brilliance, sharing space with fist-sized barnacles, blood starfish, heavily armored king crabs and bottom-hugging fish. Everything here is hunkered down with a low center of gravity, built for holding tight, adapted to riding out the four-times-a-day tidal torrents. Our near-perfect slack lasts longer than expected, 40-plus minutes without so much as a flex of the Skook’s might. Not too shabby for a dive in the fast lane.

Back on board the boat, our captain grins and announces, “That’s it for the calm before the storm. Sit down, and hold on.” We power up and surge through the building tempest, our boat buffeted left and right in the chaotic churning and frothy swirling. The current is running only a few knots now, but it could have been much faster. We smile and vow to visit again someday when it is really cranking. From the terra firma of the rocky bluff above Observation Wall, we will watch daredevil kayakers surf the standing waves cresting overtop our favorite Sunshine Coast dive site.

A Long Way from Light

There is not a cloud in the sky on our final day. The temperature seems almost springlike, a good 20 degrees warmer than the previous day, which by all rights means we should be stripping off our drysuits to bask in the sun and stare in wonder up into the blue. Yet I am in a hurry to leave it all behind. A siren lives in Agamemnon Channel, down somewhere far below in darkest night. And for me, resistance is futile. No Sunshine Coast expedition is complete without a dive under the Powerlines.

We plunge over the ledge, surrendering to gravity. Time slips away. It feels as if we are free-falling in slow motion down Dante’s elevator shaft to hell. On one side is a featureless void; on the other, pale indistinct shapes blur by as we are pulled deeper. The harsh rasping of my breathing seems impossibly loud in this deep space, yet still I hear the siren’s call. At 120 feet we switch on our lights. Powerful beams strike the ghostly weirdness on the wall, bringing everything into focus. There are cloud sponges: bizarre cream and white convolutions sculpted by unknown hands. There are huge masses of golden tubes with spiked barrels and trumpet-shaped mouths. I half expect these Salvador Dali-inspired formations to start oozing and morphing, dripping into the abyss, and for vapors to billow forth, lulling me to sleep, luring me deeper.

Downward: 140 feet, 160 feet, 175 feet. Our descent finally ends with a fiery explosion of hot color. We are hovering beside a vertical garden of scarlet sea fans, some nearly 3 feet across. They are rare candelabra gorgonian corals — eye-searingly bright, beautiful, a mind-bending surprise in the cold stillness of the deep fjord. This is all the tropics I need.

Is this the source of the alluring song? Or is that deeper still? Next time I mean to find out.

How to Dive It

Conditions: British Columbia’s Sunshine Coast is a year-round diving destination. These inland waterways are sheltered from the open Pacific’s storms and swell. Ocean temperatures usually range between 43°F and 48°F at depth. Thermoclines are often present — surface temperatures can be 10°F warmer — and noticeable freshwater layers may be encountered, especially after strong rains and snowmelt in the interior. Drysuits are strongly recommended, and you can customize your undergarment thickness to taste. Water clarity is generally best during fall and winter, when you can expect visibility between 30 and 100 feet. In spring and summer months plankton blooms tend to reduce visibility, but it can still be clear beneath the murky surface layer. Weather above the waves varies widely, from the region’s namesake sunny and warm to cool and rainy when Murphy’s law is in effect. With a full gamut of dive sites available — deep walls, shallow bays, current-swept passes, shipwrecks, etc. — there are spots suitable for divers of all skill levels and interests.

Currents/tides: It is critical to dive Skookumchuck Narrows on a favorable slack tide. Consult current tables for Sechelt Rapids (#4200) at tides.gc.ca/ENG/data#s1 to pick a suitable day. Make sure you also confer with experienced local divers, divemasters and boat captains. Each dive site in the Narrows behaves differently. It is essential to dive via a live boat. Many of the other dive sites along the Sunshine Coast are not current sensitive, ensuring you always have options regardless of when you visit.

Getting there: BC’s Sunshine Coast can be accessed by car and ferry or by floatplane. (The former combination may be more practical for divers with considerable equipment.) Our journey began in Spokane, Wash., and continued as follows: Drive five hours west to Seattle; drive two hours north on Interstate 5 to the Canadian border; cross the border via the SR-543 “Truck Crossing” right before Blaine into British Columbia; then spend another hour on the road, bypassing Vancouver city by taking Highway 15 to Highway 1 West to the ferry terminal at Horseshoe Bay; drive onto the ferry bound for Langdale (check the schedule at bcferries.com) for an enjoyable 40-minute crossing; then enjoy the final two-hour drive up the Sechelt Peninsula on Highway 101 through Sechelt and other quaint towns to Egmont.

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2018 |