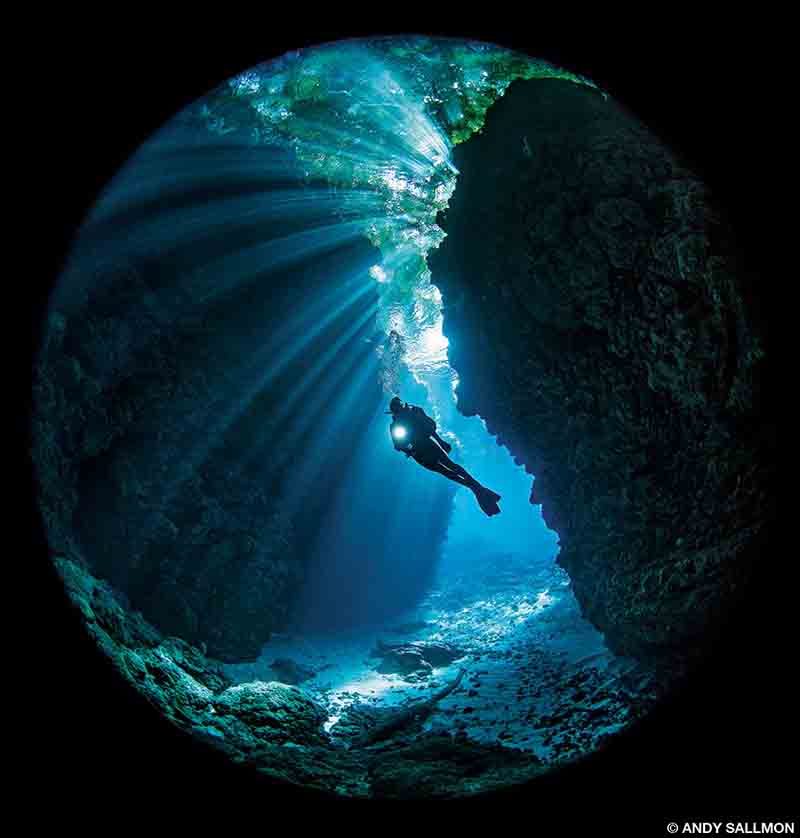

Shooter articles in Alert Diver are about legacy: a place earned through decades of commitment to the art of underwater photography. They are also about the ability to consistently communicate a technically refined and unique vision of the underwater world. Andy Sallmon and Allison Vitsky Sallmon have compressed the time usually necessary to gain their rightful spots at the top through hard work, passion, collaboration and a little friendly competition.

Andy Sallmon

Andy was the first of the pair to realize that he would spend his life underwater. The die was cast at age 4 as he held onto his father’s back for a swim to the end of a pier in Santa Cruz, Calif., impervious to the cold and exhilarated by the waves. He lived in inland Northern California, however, so ocean interludes were rare, and most of his aquatic adventures took place in lakes and rivers. His first dive experiences were not in the ocean but in Lake Tahoe on the border between California and Nevada.

Andy was 21 at the time and a bartender on a Lake Tahoe cruise boat. When he and a buddy heard about a new local dive shop, they became its first students, doing their training dives in the lake and going to Monterey, Calif., for their open-water dives. Andy said it was “love at first breath” off Point Lobos. He did 100 dives that first year, most from California liveaboards to hunt for lobster and abalone. He was conflicted for a while, spending time as a ski bum before his passion for scuba won out. He identified a path to the scuba lifestyle by becoming a dive instructor with the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI), so in 1980 he enrolled in PADI International College in San Diego.

The 10-week course introduced him to underwater photography with the Nikonos system, and he took more advanced photography courses as his electives. In December 1980 he became a PADI instructor, but after he was out of school he had no access to its cameras and no money to buy one of his own. Then he saw an ad for a Nikonos II for $60 in the local thrift newspaper. He could barely afford that, and he figured it was probably stolen. It turned out the seller was a Navy camera repairman in Coronado, Calif., who would scavenge parts from various flooded cameras to cobble together ones that functioned, more or less. Next Andy scrounged a Sonic Research SR2000 strobe, but lacking money for arms or a camera tray, he dived for the next several years with his camera in one hand and his strobe in the other.

Soon Andy made his way to the relatively warmer and much clearer water of the Hawaiian island of Maui as a dive instructor for Central Pacific Divers. He was not making a lot of money, but he got to dive for free at Molokini Crater and Lanai at a time when it was not uncommon to see hundreds of whitetip reef sharks cloaking the seafloor and mantas swirling above. He eventually expanded his gear collection to include an Ikelite Substrobe 150 and a Nikonos IV camera. Being a dive instructor in paradise was not a forever job though, and he preferred life on the mainland. He moved back to the San Diego area about five years later.

Back in California, Andy began making a name for himself by winning photo contests, notably the Nikonos Shootout and the Monterey Shootout. He taught underwater photo classes and became a representative for strobe and housing manufacturer Sea and Sea. He started contributing marine-life images to photo CDs that were being sold at the time, contributed to a series of Lonely Planet travel books and worked with Monterey Bay Aquarium to create huge backlit transparencies for their displays. In 2009 he met Allison Vitsky.

Allison Vitsky Sallmon

Allison grew up in Jacksonville, Fla., spending her time swimming and hanging out at the beach. After graduating from Boston University with a degree in communications, she headed to the University of Florida to study veterinary medicine. Diving did not appear on her radar until her mom got the idea to do a family dive trip to Cozumel in 1992. Allison reluctantly agreed to be her mother’s dive buddy and signed up for a scuba course. In the caves and springs of nearby Gainesville, Fla., her passion for all things scuba took root; by the time she went to Mexico later that year, she had logged more than 100 dives.

Diving took a back seat to school for a while. In 2003 Allison had completed vet school and her residency and was back in Boston for a postdoctoral fellowship. Eager to have diving as a part of her everyday life, she became part of the dive community in Gloucester, Mass., and immediately fell in love with temperate water. Her drysuit kept her warm, and her overwhelming curiosity about the cold, rich marine environment kept her engaged. Life was good for the young veterinarian until all of a sudden it was not.

At age 33 Allison was diagnosed with breast cancer. She wrote about the experience in the Fall 2017 issue of Alert Diver (AlertDiver.com/Pink_with_Purpose): “I’m a 14-year survivor of grade 3 triple negative breast cancer.… At 33, every breast cancer survivor I knew was 20 years or more my senior.” The surgeries and rehabilitation she underwent on her road to survival have not defined her life, but they led her to create Dive into the Pink, a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that raises money for breast cancer research and patient support via engagement with the dive community.

About the time Allison was well enough to get back to diving, she got from an ex-boyfriend a Sea and Sea DX-1G, an early amphibious compact digital camera with a strobe that she took with her on her very first warm-water exotic dive holiday — to the Solomon Islands. Allison thus earns the honor of being the first shooter profiled in Alert Diver who never shot film underwater — whose entire career has been in digital photography. It is certain she will not be the last.

The photography Allison did during her Solomons trip left her yearning to quickly get better. Two Wetpixel.com moderators who were on the trip gave her sage advice while on the boat. Upon returning home, she read all the underwater photo books that she could find — by authors such as Martin Edge, Michael Aw, Stephen Frink and others. As much as she loved temperate water, she was not a fan of the snow and cold topside, so she moved to San Diego, bought a digital single-lens reflex (dSLR) camera and joined the dawn patrol of active divers to sneak in a beach dive before work in the morning. She would often show up to histopathology rounds with wet hair and dents from her face mask still marking her cheeks. Within a year, she began entering photo contests, almost immediately winning placements in a big international competition. One of the judges was Andy Sallmon.

Andy and Allison were active divers in Southern California, but their paths never crossed until they met at a film festival. They were in other relationships at the time, but they became friends over the following year.

When asked how they realized they had found true love, they both said it came down to diving. They contended that people either love California diving, or they temporarily enjoy it but eventually stop doing it. All Andy and Allison really wanted to do on any given weekend was to jump on a dive boat, take pictures and not have to apologize for it.

When things began to get serious between them, Andy had a soul-searching moment with Allison. “You aren’t going to quit diving on me, are you?” he asked. By way of an answer Allison led him out to the garage and opened the door on a dive locker containing three drysuits, several wetsuits, dozens of single- and double-tank rigs, multiple regulators and computers and all the other paraphernalia of a woman clearly hooked on scuba. It was a match made in heaven.

Today, in addition to their regular contributions to the pages of Alert Diver and elsewhere, Andy is a sales representative for Sea and Sea, Seacam, Light and Motion, and Beneath the Surface, and Allison is a veterinary pathologist. She made the following comment about their partnership:

“Working as a team is incredibly rewarding but really hard at times. We treat each other equally, never condescending toward the other, and we always share modeling duties. We try to keep it very fair, but of course if Andy is the model and I finish getting my shots right about the time 30 divers descend upon us, or the current brings a brown mass of turbidity upon us, or the very skittish harbor seal I was photographing decides to swim away, it’s absolutely not my fault. I don’t feel bad about it, and neither would he!“

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2018 |