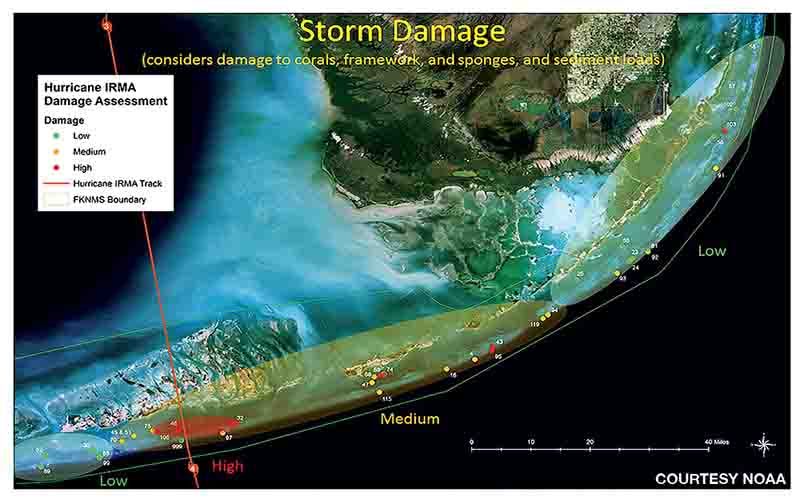

The eye of Hurricane Irma passed over the heart of the United States’ only living coral barrier reef on Sept. 10, 2017. While communities in South Florida and the Florida Keys faced significant impacts to their homes and businesses, a team of passionate scientists, managers and divers grappled with how to quickly assess the Category 4 storm’s effect on the natural coral reef system and what, if any, emergency interventions could facilitate coral reef recovery.

Within days of the storm’s passage, administrators and researchers from across the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and several partner agencies and local organizations had put in place a plan to conduct a rapid assessment of the Florida Reef Tract. Another team prepared to mobilize for potential coral rescue efforts.

This unprecedented endeavor in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS) and Biscayne National Park resulted in the assessment of 57 sites. Teams identified 14 sites that needed some level of response to stabilize corals. Sanctuary staff and local research partners identified an additional five locations for possible coral rescue.

Logistics

Determining how to efficiently assess such a large reef area presented a considerable logistical challenge when local residents were still reeling from severe storm damage and boats and boat ramps were damaged or destroyed. The answer came in the form of a liveaboard vessel that carried science divers from a host of organizations and institutions. The 65-foot M/V Shear Water, captained by Jim Abernethy of Scuba Adventures in Lake Park, Fla., allowed for an independent, 11-day operation with limited support and shore access.

Dive sites ranged in depth from 5 feet to 50 feet, and teams of five people conducted repeated dives daily using dive computers and managing their own surface interval times. A separate shore-based operation, utilizing the same methodology and techniques, surveyed the reef tract north from Miami-Dade through Martin County.

Site Selection

With a reef tract stretching nearly 360 linear miles, local managers and scientists opted to target offshore, inshore and patch reefs such as those in the following high-priority locations:

- Reef sites considered ecologically healthy and diverse

- Reef sites with the highest user visitation

- Sensitive reef sites with one or more species of endangered or threatened coral or areas suffering from bleaching and/or disease

- Highly studied and/or monitored reef sites where previous data exist on coral, fish and other metrics including species diversity, species richness and incidence of bleaching and/or disease

- Reef sites in specific managed zones within the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary that protect habitat, support research and separate human uses such as diving and fishing

Protocols

The team designed surveys to meet two primary goals: (1) Assess reef locations for damage and the immediate need for triage and coral stabilization, and (2) provide an update on the status of coral disease and, in particular, information on an ongoing coral disease outbreak in the Upper Florida Keys to Marathon, Fla.

Dive teams categorized sites by the following three tiers:

- Tier 1: severe impact — top priority for coral stabilization/triage

- Tier 2: moderate impact — secondary priority if resources allow

- Tier 3: minimal impact — not ideal for triage

Divers also collected data on the presence of coral disease and breakage as well as information on the composition, density, size and abundance of reef fish species. A geographic information systems (GIS) application specifically developed for this purpose conveyed the information to land-based decision makers.

Response

The assessment showed reef damage that ranged from large coral heads having been overturned or tossed into sand to extensive burial and breakage. In particular, previously known dense thickets of threatened staghorn and elkhorn coral suffered significant breakage. Although this weather event was a natural process, its widespread nature and strength, combined with the overall conditions of reefs in the region, prompted managers to call for an aggressive response.

Previous work has shown that rapid and selective stabilization of storm-generated fragments significantly increases the total number that will recover. Stabilizing represents a cost-effective and timely restoration technique compared with rescuing corals following vessel groundings or growing corals in nurseries for outplanting. For massive, slow-growing coral species such as brain coral or star coral, this process preserves colonies that are often hundreds of years old and a key part of the population. For faster-growing species such as elkhorn corals, the rescued fragments can help restore reefs and build the next generation of habitat.

Response actions in their simplest form may involve overturning dislodged corals, moving them to stable substrate and wedging them into a crevice or attaching them with epoxy. However, the large corals that were the target of much of this work often required the use of a broader set of tools.

Upon identification of a coral that could not be righted by diver strength alone, researchers deployed a surface marker buoy to alert a heavy-lift team made up of former U.S. Special Operations forces combat and salvage divers. The team included three lifting specialists and safety divers both in the water and on the surface. Once the team rigged a coral and achieved neutral buoyancy with a series of lift bags, they would carefully maneuver the coral to a stable area on the reef and then deploy another surface marker buoy to indicate that the dive team was ready for the vessel crew to create a mix of cement, sand and seawater. The crew then dropped this thick, claylike concrete in five-gallon buckets via a downline. Depending on the size of the corals and complexity of the lift, dive teams addressed anywhere from two to 20 corals per dive. These detailed and well-choreographed exercises often resulted in saving thousands of years’ worth of coral in a single dive.

The guiding principle for the coral rescue effort was “do no harm.” In some cases displaced corals may be just fine the way they are. It takes a specially trained eye to understand the benefit of action versus inaction. At most surveyed sites, as many corals were left in their posthurricane position as were moved, overturned or stabilized.

All of this work was done under permit within either state waters or the protected waters of Biscayne National Park and FKNMS. Permits provide a mechanism for ensuring minimal impact to the seabed and associated natural habitats, species of concern and historical resources and from activities conducted in the sanctuary’s marine zones.

Next Steps

This initial assessment and coral rescue effort took place within a small portion of the Florida Reef Tract, and the one observation that was consistent throughout the sanctuary was damage caused by marine debris. Comprehensive removal of marine debris will be necessary to speed, and in some cases allow for, natural recovery. FKNMS, with its many partners, will continue to evaluate storm impacts to inform management decisions and potential updates to existing regulations and marine zone boundaries that are designed to protect resources while allowing for sustainable use.

Contributors

The rapid assessment and recovery missions could not have happened without the expertise and contributions across myriad federal and state agencies, academic institutions and nongovernmental organizations. This collaborative effort included multiple NOAA programs: Office of National Marine Sanctuaries, Fisheries Office of Habitat Conservation, Restoration Center, Southeast Regional Office, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science and the Office for Coastal Management’s Coral Reef Conservation Program. Additional partners included the following: Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, U.S. National Park Service, Nova Southeastern University, Coral Restoration Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, Florida Aquarium’s Center for Conservation, Mote Marine Laboratory, Force Blue, and the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation.

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2018 |