Some 7 million years ago, nature began crafting a great gift to divers when a colossal rift appeared in the earth’s crust along what is now North America’s West Coast. About 3 million years later, fault lines, volcanism and fulcrum effects wrenched open a splinter of peninsula, where the Pacific Ocean filled the open end to form a marine gulf about 700 miles long, reaching maximum depths of nearly 10,000 feet.

Scientists labeled this area the Gulf of California, but this geological wonder between Mexico’s mainland and the Baja California Peninsula is more popularly known by its Spanish moniker: Mar de Cortez — or, in English, the Sea of Cortez.

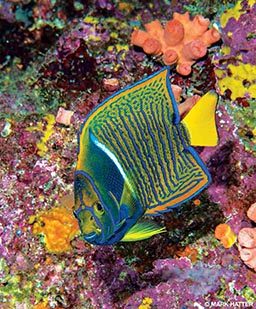

To divers, the Sea of Cortez is like a gift from nature: The biodiversity below the water is extensive with more than 6,000 unique animals. Because of the gulf’s length and location, the southern area features tropical and desert climates, while the northern end is more temperate. It’s no wonder Jacques-Yves Cousteau dubbed this sea “the aquarium of the world.”

To fully appreciate the Sea of Cortez, divers should explore it in its entirety; multiple land-based options and several liveaboards are available. One liveaboard specializes in traversing the length of the sea. As a photographer, I opted for the liveaboard, as it provided me access to exclusive, remote sites unavailable to land-based operations.

If your trip calls for more topside sightseeing, a stay in one of the larger towns with dive tour operations, such as La Paz or Loreto, can still get you in the water with outstanding creatures such as sea lions and whale sharks.

Cabo Pulmo National Park

For liveaboards and land-based operations alike, Cabo Pulmo National Park on Baja’s southeastern end marks the beginning of a typical diver’s journey up the length of the sea. It’s a fitting point of origin, as Cabo Pulmo hosts North America’s northernmost reef-building hard corals, with as many as 18 different hard coral species in these 20,000-year-old formations.

Overfishing nearly destroyed the few fragile reefs at the southern end of the sea in recent decades. In the 1980s the coral John Steinbeck so richly described in his 1951 narrative, Log from the Sea of Cortez, was all but gone. In 1995 Mexico established the Cabo Pulmo National Park, a marine protected area covering 27.5 square miles of Cabo Pulmo reef, and the marine life quickly rebounded. The park, as part of the larger Islands and Protected Areas of the Gulf of California, was designated a United Nations Education, Science and Culture Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Site in 2005.

When my companions and I rolled into the water, immersing ourselves in a swirling school of bigeye jacks, we witnessed firsthand the park’s success. We watched the school’s fluid shapeshifting for an entertaining half hour before we drifted down current to see more reef superstars, as groupers, snappers and giant surgeonfish of several genera joined the parade.

Back on the liveaboard, we congratulated ourselves for completing an excellent wide-angle shoot, but I somberly remembered that Cabo Pulmo National Park’s success story is tentative. The area’s foundational reefs, which support the fish populations, remain exceedingly fragile and face challenges from illegal poaching and climate change.

When shooting in the Sea of Cortez, versatility is key. One dive with swirling jacks and large creatures may be perfect for wide-angle shots, while the next dive might call for shooting macro. I learned this lesson at Isla Cerralvo when my roommate processed a stunning headshot of an alienlike clubhead barnacle blenny peering out from its shell. I wanted to add this cool little macro subject, which is commonly found among the rocks at safety-stop depths, to my own image collection. Alas, a 13-day charter leaves little time for delay, so another dive on Isla Cerralvo was not in the cards. Fortunately, the clubhead blenny is quite common at the tropical end of the Sea of Cortez.

La Paz

Between Cabo Pulmo and Isla Cerralvo are dozens of dive sites inaccessible by day boats; we found time to explore only a few. Exclusivity diving begins to change near the coastal city of La Paz, so our liveaboard crew shrewdly set us on the popular Fang Ming wreck off Isla Espíritu Santo before breakfast and the arrival of the day boats. The Fang Ming is festooned with trees of black coral growing off the base of the hull at around 65 feet. With the divemasters predicting nudibranchs, moray eels and garden eels galore, we elected macro rigs for this wreck dive.

At the ship’s stern, one diver found a longnose hawkfish flitting back and forth along the length of a particularly large black coral tree. While some divers patiently lined up for a turn to shoot this uniquely tropical fish, I moved on to the garden eel colony in the sand off the wreck to take on the nearly impossible challenge of creeping in for a decent portrait.

Our next stop was the widely popular Isla Los Islotes, a protected marine reserve accessible by day boats arriving from La Paz. Despite the crowds, we spent the whole day at Los Islotes because the diving was spectacular. Conditions were perfect: a smooth sea, clean blue water and visibility in excess of 100 feet. Los Islotes is a classic wide-angle photography site offering a swim-through arch, schooling fish of many different genera and the animal all divers want to encounter — the California sea lion. My friend Ron Watkins calls them the “ambassadors of the Sea of Cortez” — a congenial term with which I completely agree.

Our captain and divemasters once again got us in the water before anyone else, and we happily had the arch and the underwater residents all to ourselves. Almost as soon as we rolled into the warm, blue depths, several playful ambassadors approached us, giving us a difficult decision: Pass through the arch and navigate the west wall back to our point of entry, or dally with the sea lions?

We chose the swim-through, expecting the sea lions to wait for our circumnavigation of the small island; we made the correct decision. Passing through the arch we discovered a reef bustling with schooling barberfish, blue and gold snappers and shoals of schooling baitfish, which were flashing under constant assault by sundry species of marauding jacks and groupers. With the cavalcade of wide-angle-worthy subjects, it was tough to leave and ascend to our safety stop. At a usually uneventful 15 feet, I suddenly attracted the attention of a pair of sea lions who elected to use my fins as a play toy. I’m not sure how long we entertained each other, but it was likely the longest safety stop I’d ever made.

Loreto Bay National Park

With a heavy diving schedule and precious little time to download and process images after hours, it can be difficult to tear oneself away from the computer for topside tourism. But by midweek we packed the coolers and began our sunset cruise at Isla Danzante. Our destination was Honeymoon Beach, a secluded area in Loreto Bay National Park that offers a short climb up a hill to a stunning overlook.

Encouraged by the beautiful vista, we climbed to the overlook to take in the breathtaking view of the liveaboard quietly at anchor far down the bay. The climb and descent were so invigorating that we could not help but linger under a fiery sunset.

The next day we arrived at Isla Las Animas to dive a rocky wall in a small, protected bay with an extended floor covered by an army of sea stars slowly crawling across the sand. Using a macrorigged snoot, I photographed the commensal shrimp I found among the sea stars. Later I learned that one of the divemasters had discovered a yellow Pacific seahorse (Hippocampus ingens) at the base of the rock wall; another diver found a normally drab, male gulf signal blenny (Emblemaria hypacanthus) in full nuptial display, showing his breeding colors. We made a second dive on the site to give our shooters another chance to photograph these two popular subjects.

The subtle change in water temperature seemed innocuous as we had traveled north, but the afternoon dive around the exposed point of Las Animas, outside of the bay, offered a more drastic change. We entered the comfortable 77°F water just inside of the point’s tip and followed the tide offshore. Crossing an underwater ridge, we entered a current that pushed cool, green 72°F water into an adjacent bay. What a transition!

Midriff Islands

The Sea of Cortez changes from a tropical to temperate environment in the Midriff Islands, and the list of photographic targets changes with it. While many animals can be found throughout the length of the sea, some species that are more distinctly temperate, such as the Catalina goby, become more common.

As we moved north, we replaced our 3/2 mm wetsuits with 5 mm hooded vest kits. Yet while the water cooled, the photo opportunities did not. At remote Isla San Pedro Mártir we dived with wide-angle rigs to photograph the curious and swift sea lions rocketing around us. Perhaps the chilly 69°F water made them so energetic. Whatever the reason, I was thankful for their antics, which took my mind off the unusually cool upwelling.

While the sea lions are certainly perfect for wide-angle images, the Midriff Islands offer significant opportunities for those interested in macro photography as well. Skeleton shrimp, for example, are not hard to find if you know where to look for them. These microcrustaceans often ride shotgun between the eyes of scorpionfish, but I’ve also found them swarming on sea fans along the reef walls at Los Cuervos, a dive site at Isla Salsipuedes.

For nudibranch diversity, El Caballo (“The Horse”) in the Midriffs is unparalleled. El Caballo is an undersea ridge of rock running perpendicular to the tides, the pull of which can be quite strong around the new and full moons. Regardless of the current, once you tuck in behind the wall, the micro world opens to a diverse array of nudibranchs unlike anywhere else.

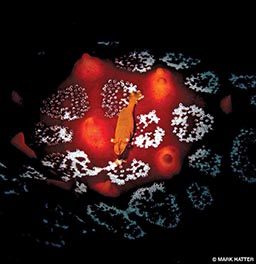

The star of El Caballo is the sea tiger nudibranch (Roboastra tigris), a cannibalistic species with a voracious appetite for other nudis. These colorful carnivores are quick to smell a nearby meal, outrace their prey and swallow it whole.

Nudibranchs aside, my favorite dive site in the Midriffs is Angel Island, where muck diving can yield great results for tiny blennies and jawfish. A great time to dive Angel Island is midsummer, when the water is warm enough for a 3/2 mm suit. Midsummer is also peak breeding season for the orangethroat pikeblenny, spotcheek blenny and bluespotted jawfish, the males of which, along with the gulf signal blenny, display impressive breeding colors.

Pikeblennies and signal blennies are usually small, cryptic, benthic fish living in tubes over rubble and sand bottom. They mostly go unnoticed until the urge to spawn has the males flashing from their protective tubes, with colorful fins flared, to attract female attention. To capture this display, be patient, find the rhythm of their flashing and anticipate when to pull the camera trigger. You can use a similar technique with the much larger burrow-dwelling bluespotted jawfish, which follows a similar pattern of flashing. A colony of resplendent nuptial males can seem like a game of whack-a-mole.

Bahía de los Ángeles marks the northernmost boundary and a fitting end to the journey for diving the Sea of Cortez. At Bahía de los Ángeles you can take a quick, shallow dive at the mouth of the bay for the hydrozoan-loving Flabellina iodinea nudibranch, followed by a half-day snorkel trip with the world’s largest fish: the whale shark. The large, shallow bay holds a resident population of whale sharks, spawning a reliable eco-industry for the local fishermen, who struggle with overfishing in larger, unprotected parts of the sea. They host day-trip and liveaboard guests on their pangas — boats once used for fishing but now used for snorkeling with whale sharks.

The shallow bay is warm — perfect for snorkeling in just a T-shirt. The whale sharks generally ignore the snorkelers, likely from a strictly enforced “no touch” policy coupled with a mandate that each shark encounter is limited to no more than four snorkelers at a time. Our energy and anticipation were high as we found and swam with our first shark of the day. What initially seemed like a rare and epic encounter became routine. One by one we photographers and snorkelers got our fix. The panga operators eventually took us back to shore or to the liveaboard, tired but happy.

On the overnight haul back to Puerto Peñasco, our debarkation point at the northern end of the sea, I reviewed my images. With many subjects left to shoot, I promised myself to book another trip next summer, this time starting in the north and following the sea to its southern reaches.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2018