The white sandy beach, the surrounding cliffs and the deep blue just feet away make Dean’s Blue Hole in the Bahamas a safe haven for us and a mecca for freedivers worldwide. It is the second-deepest marine sinkhole in the world, yet it is accessible from land. Harboring coral reefs and other marine life, it is an ideal oceanic microcosm, sheltered from prevailing winds and boats — the perfect lab for our research. Not far beneath the sea surface, a series of limestone ledges form a narrow shaft leading to a large room that expands down to 663 feet (202 meters).

Dean’s Blue Hole is connected to the ocean through a shallow bay and is easy to access once on Long Island. But this remote outer island has limited resources. We plan our scientific expeditions weeks in advance to ensure we bring everything we need, have a complete assessment of possible risks and have our daily dives organized. The logistics of science expeditions are critical to meet project goals and funding limitations. We also train continuously to keep ourselves ready for the demands of our dives.

We are on a mini-expedition to service a hydrophone tied to the wall of the blue hole at around 50 feet (15 meters). As freedivers, we will be doing breath-hold dives. To prepare for our short dives, we did not have to fill tanks or haul heavy scuba gear on the soft sandy edge of the hole. Our plan this morning is to remove the hydrophone from its bracket so we can service it at our nearby local villa. The hydrophone has been recording unique passive acoustic data for nearly a decade, documenting for the first time the soundscapes of a marine sinkhole. The tidal flow orchestrates the distinctive sounds of the blue hole’s sand falls and resident fishes, punctuated with occasional calls of freedivers doing a mouthfill and even moans of whales penetrating through what could be caves in the limestone from the adjacent Atlantic.

Today the blue hole is at its best. It is one hour before low tide, and the ebbing seas have left a calm glassy surface. From shore we can clearly see the first underwater ledge with juvenile jacks darting along the sandy slope. We gear up with our two-piece wetsuits, low-volume masks, long fins and, most important, the correct amount of weight on our elastic belts so we are positively buoyant at the surface on an exhale.

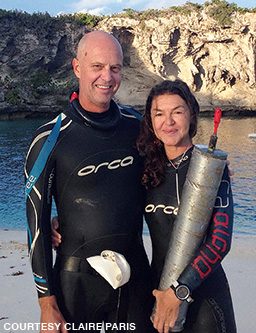

With our float and drop line, we take a few steps before we are suspended over the deep blue. The sandy ledge behind us funnels into beautiful sand falls. With a few more kicks we cross the opening of the hole and can see the hydrophone below the first ledge. The resident barracuda has already come to greet us. I signal to my husband and dive buddy, Ricardo, to let him know I will dive first. I am already feeling good because we did our stretching and breathing exercises early this morning. Now I need a few minutes to relax and prepare for our first reconnaissance dive.

I take my peak inhale, bend and begin my slow vertical descent. I know how many kicks it takes to pass the first ledge. I flatten out and face the hydrophone. A lot of growth is on the cylinder casing, but the lines are in good shape. The nuts on the bracket are loose enough to turn by hand. Keeping my dive brief, I return to the surface. Ricardo has been watching me the whole way and coaches me through my recovery breaths and OK sign. “Looks good,” I tell him after my recovery. “We won’t need the wrench today.”

Ricardo and I take turns diving to loosen the bracket, communicating between each dive, after recovery, to relay our next dive plan. We’ve done this procedure enough times and have prepared well enough to slide out the hydrophone after just a few dives of 90 seconds or less. Now we have 24 hours to download the data, service the hydrophone and redeploy. Our mini-expedition went well — with favorable weather, good visibility and quick extraction — so we have time to do some dives for fun and exploration.

I love my work as a professor in the Department of Ocean Sciences at the University of Miami’s Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science. My research is dedicated to biological oceanography and ocean conservation. While it is a great feeling to freedive in the ocean for research, it is an even bigger thrill to successfully obtain data for analysis. My first science expedition to Dean’s Blue Hole was an extension of work I had been doing all across the world.

I am also a competitive freediver. We first came to Long Island to train with William Trubridge, a holder of multiple world records and a world champion freediver. After diving Dean’s Blue Hole, I was hooked with both freediving and Long Island. I started a multiphase project there with multiple experiments, including a behavioral chamber I designed for fish larvae and used with colleagues in Australia, Belize and South Florida. During that first Long Island expedition, explorer and cave diver Brian Kakuk helped me install the hydrophone to continuously study the sounds of the blue hole.

A few years ago we determined that other researchers and students could benefit from learning the freediving skills we were applying to our underwater research. They could use such techniques in various studies, including those that involve observing subjects, sampling, tagging, deploying and servicing moored instruments, laying transects, researching plankton and outplanting coral. Freediving can facilitate scientific research where sites and tasks are within a safe breath-hold depth. Some scientists who use freediving to study corals, sharks and whales wanted a scientific freediving course to help them establish safety protocols and improve their team members’ freediving skills.

At that time Ricardo, who has a degree and experience in marine sciences, had been teaching freediving courses for almost 10 years and had assisted me with fieldwork on various expeditions. We had competed in several international freediving competitions, and he helped coach me to four U.S. national records. We understand freediving risks and know well the importance of safety.

Recreational freediving courses teach students about safety, techniques and the benefits of descending and ascending on a breath-hold. Our scientific freediving course would focus on additional skills required for safely planning and executing dives on a breath-hold to perform tasks at depth. Just as high-altitude expeditions require guidance from mountaineering experts, scientific freediving expeditions need guidance from scientific freediving specialists.

We collaborated with friends and colleagues to draft a course that would raise awareness of the risks, promote safety, teach the required skills and establish guidelines for freediving in science. We worked closely with the risk management department at the University of Miami to demonstrate how the course would better prepare students and researchers and mitigate fieldwork risks. Everything seemed to fall into place in 2018 when the Rosenstiel School began construction of the state-of-the-art scientific dive training facility called The Splash. The 15-foot-deep pool and the small fleet of research vessels would be ideal resources for our required water sessions.

The school approved our scientific freediving course, which was available to students for Spring 2020. With registration limited to eight students to provide a safe teacher–student ratio, the course immediately filled with four graduate and four undergraduate students and a few more on a waiting list.

The course offers two tracks. Track one is for full certification as a beginner (Level 1) freediver, which provides training for dives to 30–50 feet (10–15 meters), or intermediate/advanced (Level 2) freediver, which provides training for dives to 65–80 feet (20–24 meters) and for scientific freediver academic course credits. Track two is for those who do not achieve freediver certification but take the course for scientific freediver academic credits. In addition to providing the general skills required to plan and safely conduct underwater research and fieldwork, the course includes the DAN® Basic Life Support and Emergency Oxygen training.

In the first few months of the semester, we covered the history and evolution of freediving, physics, physiology, safety and rescue, and applications to science, and we began our in-water sessions at The Splash facility. We had planned to begin underwater skills and scientific task practice in March, but COVID-19 changed everything. In our “dry and distant” online teaching, we covered important learning objectives for scientific freediving such as logistics, risk assessment, safety plans, gear preparation, and marine mammal and freediver physiology. Guest lecturer Peter Zuccarini spoke about underwater cinematography and how freediving has allowed him to get close encounters with animals.

The Rosenstiel School’s scientific freediving course is the first of its kind. Other academic institutions, scientists and instructors want to introduce similar courses, so we are developing a scientific freediver specialty certification training. The course represents a much-needed foundation to establish safety protocols, plan underwater fieldwork and prepare students for other scientific freediving specialties. With the support of other researchers and educators worldwide, we are pleased that our scientific freediving course will make scientific fieldwork safer.

Explore More

Learn more about the research and freediving work of Claire Paris in this video.

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2020