There are few Caribbean dive destinations with as much personal resonance to me as Cayman’s Sister Islands. I first visited Cayman Brac and Little Cayman in 1982, as they were on my hit list (along with their more populous and prosperous sibling, Grand Cayman) for my first-ever travel assignment for a dive magazine. In later years I would be back as a staff instructor for Cayman Brac’s Nikonos Shootout, a photo event that brought a couple of hundred underwater photo enthusiasts to the island for a week of competition, big prizes and lots of fun.

I’ve photographed unusual and charismatic marine animals that chanced upon these islands over the years, including Spot (a bottlenose dolphin) and Molly (a manta ray). Each has since moved on, but for a while they were reliably encountered, adding yet another element to the already significant portfolio of underwater photo opportunities in these islands. I even chose Cayman Brac as the destination to shoot the underwater lifestyle pictures for Nikon’s product catalog that introduced the Nikonos RS camera system in 1992.

The south sides of both Cayman Brac and Little Cayman offer isolated concentrations of nicely intact elkhorn coral.

But that was then, and this is now. Despite more than three decades of diving these islands, I continually find inspiration. In more recent years I’ve chosen Little Cayman as the setting for my digital masters classes for the simple reasons that the water is so clear, the reefs are so colorful and target-rich, and the fish populations are so tame and tolerant. Backscatter Underwater Video and Photo has done the same, hosting their Digital Shootout in Little Cayman every other year. What makes these islands so special?

From a diver’s point of view, the Cayman Islands are small bits of land that rise from the sea, the upper elevations of a submarine ridge that extends from Belize to Cuba, rising 25,000 feet to form the northern edge of the Cayman Trench. Created by volcanic activity more than 50 million years ago, the structure is nearly vertical, at least underwater. Larger pelagic species ply the deep water surrounding the islands, and the shallow mangrove-shrouded lagoons along the shores provide an ever-replenished nursery for fish that ultimately migrate to the coral reefs. Add to that a legacy of marine conservation, and the conditions are propitious for diverse and abundant marine life.

The above-water geography is quite flat. Cayman Brac’s high point, a bluff at the east end of the island, is 140 feet above sea level, while Little Cayman’s is only 40 feet above the surface. Cayman Brac’s total area is just 15 square miles, and Little Cayman’s is 10. Such small islands have very little runoff to degrade visibility. With no rivers and minimal population influences, there are few Caribbean islands that have less terrestrial impact on their underwater wonders. Water clarity benefits as a result.

Situated south of Cuba and northwest of Jamaica, the islands are just 450 miles south of Miami. This makes for a short flight, but the islands are a world away. There are only about 200 full-time residents on Little Cayman and 2,000 on Cayman Brac. Of course, the number of dive tourists can swell the population at any given time, but even so the resorts are small, intimate and highly targeted to the scuba lifestyle.

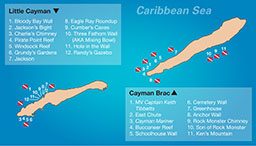

The Cayman Islands Department of Tourism has officially named 365 dive sites surrounding Grand Cayman and its sisters, one for each day of the year. Of these they attribute 65 sites to Cayman Brac and 60 to Little Cayman. There is enough dive diversity to occupy even the most dedicated diver for a two-week holiday. Most dive sites can be reached in 10 to 20 minutes. The farthest one might ever cruise to a site would be about 45 minutes, and that would be for special expeditions — to sites along the bluff on Cayman Brac, for example, or to commute between Little Cayman and Cayman Brac. Most dive packages for either island will include at least one day visiting the other. From Little Cayman you’d want to visit Cayman Brac’s Tibbetts shipwreck, and divers on Cayman Brac wouldn’t want to miss at least a day on Bloody Bay Wall. Wrecks, walls and shallow reefs are the underwater attractions that drive tourism in the Sister Islands. The topside ambiance is quiet and laid back, and for many that’s a highlight.

Cayman Brac

Cayman Brac is 12 miles long but only 1 mile wide, with the western part of the island flat and relatively featureless aside from Ironshore Formation limestone on one side and a white sandy beach on the other. There is a scenic limestone bluff to the east that gives the island its name (brac is Gaelic for “bluff”). Most of the diving is along the northwest tip of the island, with the most popular wall dives and the iconic shipwreck MV Captain Keith Tibbetts a short boat ride from the island’s most popular dive resort. These sites are also the nearest reach for day boats traveling to the Brac from Little Cayman, but with so little boat traffic and such good cooperation among dive operators there are always open mooring buoys on Cayman Brac.

Several shallow reefs lie near the wreck, making it perfect for a morning two-tank dive featuring a wall or the Tibbetts for the first dive and a long, leisurely second dive on a high-profile spur-and-groove reef for the second.

The Captain Keith Tibbetts is perhaps the most noteworthy of Cayman Brac’s sites, if only because it is the only really compelling wreck dive on either of the islands. There are other historical shipwrecks, such as the Prince Frederick and the Kissimmee on Cayman Brac and the Soto Trader on Little Cayman, but these are smaller vessels and don’t offer the marine life habitat or dramatic structure of the Tibbetts.

Sunk as a dive attraction on Sept. 17, 1996, the wreck is alternatively known as “the Russian destroyer,” although that is not an accurate appellation since it’s a frigate, not a destroyer. Built in 1984 in Nakhodka, Russia, it carried the designation number 356, which for many years was still visibly emblazoned on the hull. The wreck is 330 feet long with a 43-foot beam. It had been mothballed in Cuba when it was acquired by a consortium of dive operators and the Cayman government, then cleaned of contaminants and placed along a sand slope with the bow rising from about 110 to 80 feet and the stern deck at about 45 feet. It is an easy multilevel dive with no current and, more often than not, extraordinary water clarity. The Tibbetts holds some resident fish, most notably barracuda and goliath grouper, but it is the rich sponge colonization that best defines this wreck. There are still gun emplacements fore and aft, which is unusual for those used to diving shipwrecks provided by the U.S. government, which normally removes the gun barrels prior to donation.

The Tibbetts’ superstructure is aluminum, which in combination with its 10,000-horsepower turbine engines meant it was light and fast (it could cruise at up to 30 knots). The electrolysis between the steel bow and aluminum superstructure combined with the ravages of surge have twisted and broken the ship, but it remains one of the most iconic underwater attractions of the Cayman Islands.

One of my favorite wall dives is East Chute and what used to be the wreck of the Cayman Mariner. Once a crew boat working in the oil patch off Louisiana, years of storms have pounded it into little more than a debris field with at least one photogenic porthole remaining. You probably wouldn’t go out of your way to dive this shipwreck, but it does mark the beginning of a deep sandy valley that punctuates the wall here. The vertical face of the wall begins at about 70 feet, and large coral mounds surrounding the valley rise to about 45 feet. Green tube and orange elephant-ear sponges decorate the wall.

Many of the Brac dive sites earned their names from shore structures that boat captains used as references before mooring buoys were installed. Buccaneer Reef, Schoolhouse Wall and Cemetery Wall are examples, as is one of the easternmost sites along the island’s north side, Greenhouse. The topography is typical of many of the island’s shallow reefs, with familiar parallel spurs of coral. Many are ancient star corals, undercut and now mushroom-shaped. Given that these coral heads were likely alive when Blackbeard used to hide out on the Brac, a little erosion with age is to be expected. The crevices along the coral canyons are populated with grunt and schoolmaster snapper, and large green morays can be seen freely swimming about the reef. Butterflyfish are well suited for foraging amid the reef crannies, and it is common to see angelfish here as well.

Because of the prevailing winds, much of the diving is done off the west and north sides of the island, but there are several great sites off the southern and eastern shores. Anchor Wall is a particularly photogenic south-side site with a giant and very old anchor embedded in a deep coral crevice about 4 feet above the seafloor at 100 feet. Orange encrusting sponge now decorate the anchor’s shank and flukes; to give a sense of its immense size in the photo, I like to bring a model in from the seaward side, just behind the anchor.

Although it is a long run, most dive operations try to get their groups to the east end, weather permitting, at least once during their stay. This trip gives a nice overview of the island’s topography, particularly the bluff, which is all the more imposing when viewed from sea level. Rock Monster Chimney, Son of Rock Monster and Ken’s Mountain are all popular destinations for a bluff run. Here the wall begins at about 60 feet, with giant sand canyons that cleave the substrate. The crevices are overgrown and provide swim-through tunnels along the wall. There may be more current here than along the island’s west side, but the payoff is visibility that can exceed 150 feet. There is so much high-profile shelter from flow that current tends not to be an issue anyway.

Little Cayman

Lying 7 miles from Cayman Brac and 86 miles from Grand Cayman is Little Cayman. If you were given a blank slate and a magic pen and were told to create a dive destination, you just might draw Little Cayman. First, make a 9-mile-long and 1-mile-wide oblong shape. Then add a little 11-acre patch of an island off the south side, near enough to kayak to but far enough away to serve as a bird sanctuary (that would be Owen Island). Then add some scenic white sand beach along the island’s south side, and on the north side, which features the best diving, make an ironshore to keep the visibility optimal. Put some high-profile spur-and-groove coral formations along the south side so there’s good diving no matter the wind direction.

On the north side render a wide, shallow plateau that could host high-profile star corals and lots of gorgonian. Carve out a vertical wall that begins as shallow as 18 feet and then plunges to 6,000, and have it all washed by the indigo waters that pass through the Cayman Trench. Make sure it is semiarid with no rivers to ensure the best possible water clarity, and then keep the population tiny to minimize the impact from cars or sewage. Sprinkle in lots of sea turtles, friendly grouper and large schools of grunt and schoolmaster snapper. Add a few sharks, some eagle rays and some green morays, and then on top of it all lay a marine park so that all the pretty things you envisioned are protected and preserved. Then you would have Little Cayman.

When I was there last October we had unseasonably windy conditions, which I wouldn’t normally mention because it was so unusual. But it kept us diving the south side of the island for several days, and I had never before done much of that. Normally we’d motor right by all those south-side reefs on the way to the better-known sites along the north side such as Bloody Bay Wall and Jackson Bight. But this time we explored some of the southern sites, including Charlie’s Chimney, Pirate Point Reef, Windsock Reef and Grundy’s Gardens. I’m sure with more time I could come to discern the fine distinctions between these sites, but in broad strokes they seemed to offer similar hard-pan shallows that gradually build into spur-and-groove channels of high-profile corals that slope down to a sandy, 45- to 50-foot-deep seafloor punctuated by large clusters of 15- to 20-foot-high coral. All of this slopes very gradually seaward before plunging vertically from a depth of about 80 feet. The corals are quite nice and provide habitat for grouper, turtle, rays (both stingrays and eagle rays), trumpetfish, jacks and angelfish. While the frequency of significant marine life encounters here may not be as high as that on Bloody Bay Wall, these are very nice dives and sometimes deliver decidedly different vistas than those found on the other side of the island. Granted, it is hard to not choose Bloody Bay and Jackson Bight when the conditions permit, but I was glad for the windy conditions just so I could experience a bit of Little Cayman I’d never known before.

The sites along Jackson Bight have been more productive for me over the years in terms of pelagic encounters. In the prelionfish years this was the best site for seeing sharks, but these days Caribbean reef sharks often appear wherever lionfish culling takes place. The large sandy arenas of sites such as Eagle Ray Roundup are predictably good for eagle ray sightings (hence the name) as the animals swoop in to root for small crustaceans buried in the sand.

While most Jackson Bight sites feature a large coral buttress along the seaward edge of the wall, Cumber’s Caves is different. It has the usual large sand plain on the shoreward side, but this one is populated by hundreds of garden eels. Southern stingrays cruise in a tireless search for invertebrates they can suck from the sand. The site gets its name from a series of what must have been sand chutes exiting the wall but eventually were overgrown with coral at the top, creating a series of swim-throughs that begin at 40 feet and exit the wall at 60 to 120 feet. Some of the caves are rather bland, but others are colorfully decorated with sponge, which makes for stunning wide-angle photos (assuming you are quick enough to get your shot before the particulate raining down from your exhaust bubbles creates a storm of backscatter).

The Sister Islands’ most famous sites are those along the Bloody Bay Wall, and their fame is well deserved. Their names are carved into our collective consciousness and passed along from diver to diver when recalling the great wall dives of the Caribbean. At Three Fathom Wall (also known as Mixing Bowl) the wall starts (as you would expect) at 18 feet, where a large cleft in the wall divides Jackson Bight to the east and Bloody Bay to the west. Big schools of grunt surround star corals here, and vibrant sponge dot the wall, even at 40 feet and shallower. At Hole in the Wall the vertical precipice is replicated (a bit deeper here at around 24 feet), but there is a large open passageway that begins shallow and exits on the wall at 65 feet. This is the site’s namesake structure. Numerous cleaning stations provide access to typically skittish fish such as the tiger grouper, and like almost any site along Bloody Bay Wall, green sea turtles are common. Randy’s Gazebo also has a swim-through chimney that exits on the wall, but its most notable feature is a highly decorated coral condominium on a ledge seaward of the wall face.

No matter which of the dozens of Bloody Bay sites you dive, the common denominators are abundant marine life and, just as significantly, friendly fish. This is an artifact of decades of protection in Bloody Bay Marine Park. The grouper will swim right up to your face mask, totally unafraid, and the turtles will, too. Perhaps this is why it has become so popular for underwater photography. They say if it were easy, everyone would do it. Well, it is here, and they do.

How To Dive It

Getting there: The Cayman Islands, Grand Cayman in particular, are among the Caribbean’s most easily accessed destinations, with direct flights from numerous carriers, including the nation’s flag carrier, Cayman Airways, which arrives daily at Owen Roberts International Airport. The Sister Islands present a bit more of a challenge, as they require connecting flights. Cayman Brac’s Charles Kirkconnell International Airport has a 6,000-foot runway that can accommodate a Cayman Airways 737 (as well as a de Havilland DHC Twin Otter operated by Cayman Airways Express out of Grand Cayman. Little Cayman’s 3,200-foot grass and gravel runway is too small for the jet, but the Twin Otter lands there several times a day.

When traveling to Cayman Brac or Little Cayman via the Twin Otter service, the baggage allowance is 55 pounds per person (combined weight of up to two pieces) and one 15-pound carry-on. Excess is charged at US$0.50 per pound. I have found the airline to be more lenient on incoming flights because they understand that passengers typically connect from larger aircraft. On the outgoing leg back to Grand Cayman, however, they tend to adhere to the letter of their law. The baggage restrictions on the 737 to Cayman Brac are no more stringent than normal international flights. On Cayman Air, for example, the allowance is two free checked bags of up to 55 pounds each and a carry-on of up to 40 pounds.

Conditions: The water temperature is usually 81°F-85°F year round, so a 3 mm wetsuit is perfect. Air temperatures are balmy (75°F-88°F) with the occasional cold snap dropping it below 60°F. Visibility in the Sister Islands ranges from good to outstanding — 60-150 feet unless there is a strong, consistent wind. When the north wind picks up, the waves can batter the ironshore and stir up sediment on the shallow hardpan seafloor, creating turbidity. The good news is that this leaves the southern dive sites with good visibility. It takes a heavy tropical disturbance to cause days of lost diving in the Sister Islands, but with hurricanes, obviously that does happen. Some pretty heavy tropical systems have lashed the Sister Islands over the years, but they are well predicted, and travelers will generally know about significant weather in advance.

Dive operations prefer that recreational scuba be kept to 100 feet and shallower, but there is a lot of technical diving done in the Cayman Island to considerable depth. Currents aren’t often an issue, and most diving is done in reasonably calm conditions. The dive operations are professional and safe, and most operate large and seaworthy boats. There is a hyperbaric chamber in Georgetown, Grand Cayman.

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2017 |