How is a dive professional supposed to stay in shape when we’re advised to avoid vigorous exercise within 24 hours of diving? What kind of exercise is recommended for a divemaster or instructor who dives daily?

The problem you describe is, unfortunately, something of an intractable one. There is no easy solution. A compromise is almost always required. The simplest rule is that the highest-intensity exercise should be separated from diving, particularly from more extreme dives.

Some runners run every day regardless of other activities. The first recommendation for such people is that they dive very conservatively. This advice is by itself a problem since it is difficult to quantify “conservative,” and the spirit of the recommendation is not generally understood in the diving community. Diving within the limits of a dive computer or table does not necessarily constitute conservatism. There are a variety of different limits, and many divers have developed symptoms while adhering to them. Computers or tables provide estimates for a variety of people and exposures based on limited input.

A major challenge in appreciating the risk of decompression sickness (DCS) is its probabilistic nature. The fact that a diver might tolerate a given exposure once, twice or 10 times without incident doesn’t mean the exposure is safe. If DCS results from the 100th exposure, this is not an undeserved hit — the diver simply ended up on the wrong side of the probability line that day.

Humans have a tendency to let good habits erode when nothing bad happens. We tend to increase our driving speed and push depth and/or time limits on dives. Furthermore, we often fail to appreciate that we are not being as conservative as we once were. This can lead to surprise when things go bad.

This surprise can create a tendency to look for some factor to blame. With DCS, dehydration is often the scapegoat. The reality in most cases is that a similar state of hydration probably existed on many other dives. The real problem with this tendency is that it may encourage the diver to ignore the depth-time profile, which is by far the most important factor. While it can be comforting to identify a simple cause, it is a disservice to safety. The risk of DCS is affected by a large number of factors acting in complicated concert. True conservatism is required to increase the likelihood of consistently safe outcomes.

The daily runner will have a sense of the normal pains and discomfort associated with his or her exercise. Atypical pain or discomfort in a diver will raise suspicion of a decompression injury. Again, the ideal choice for this person would be to limit diving to conservative exposures. The next best choice would be to fit in the intense physical activity as far from diving as possible. It is safest to limit physical activity to that with very low joint forces — the closer to diving, the lower the forces. Modest swimming, for example, involves much lower joint forces than running. Cycling can also involve lower joint forces than running. These are not absolutes, though. It is not enough to choose an activity that might have low joint forces; it is necessary to practice it in a way that ensures low joint forces.

The practical approach is to separate physical activity from diving, with the lowest-intensity exercise closest to the diving. Swimming and walking typically produce less strain than intense cycling or running. High and repetitive joint forces should be minimized. The diver should be mindful of the activity level and honestly appraise the risk. By making small decisions that consistently favor the slightly safer option over the slightly more aggressive, an adequate safety buffer can be created.

This is not a simple answer, but reality is messy. Exercise, especially intense exercise, can increase the effective decompression stress. If it is not avoided, an honest appraisal of conditions and actions is important to control the risk. If a problem does develop, it is best to skip the denial and blame phases. DCS can and does happen, often following dives that were assumed to be safe.

Ultimately, each diver should appreciate the risks, work to control them and accept that diving involves complicated hazards. Getting bent should not be considered a personal failing. Being open to the possibility of DCS can start a diver down a very positive road of preparedness and action to reduce risk at every opportunity. Employ physical activity thoughtfully; ultimately the self-aware and self-critical (honest) diver will likely end up being the safest one.

— Neal W. Pollock, Ph.D.

I’m 56 and in good health. Three years ago I had an idiopathic pulmonary embolism. I am no longer taking anticoagulant medication, and I remain very active. Can I dive?

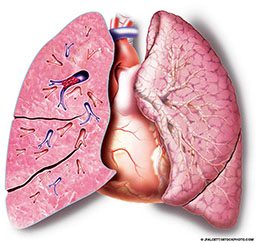

Several things need to be considered when evaluating fitness for diving after a pulmonary embolism. First is the cause, because it is important to determine the risk of recurrence. Determining this risk may be difficult in your case because your embolism was idiopathic (of unknown origin). Next the damage to the lung must be assessed. Scarring and/or adhesions may prevent proper gas exchange, making diving unsafe.

DAN is not in a position to determine an individual’s fitness for diving; a physician must make that decision. The best way to begin the process of assessing your fitness to dive is to get a high-resolution spiral CT scan to determine if there is damage to the lung tissue. If there isn’t, and exercise tolerance is normal, diving can be considered.

Pulmonary hypertension and other associated medical conditions may restrict your exercise tolerance. Certain medications can have side effects that might limit your ability to dive safely, so you should discuss all medications you take and your complete medical history with your doctor.

If your doctor approves your return to diving, request this approval in writing so you can provide documentation to dive operators, who will likely require a written statement before allowing you to dive.

— Lana Sorrell, EMT, DMT

On a recent dive a buddy rolled backward into the water, and his tank valve hit me on the head. I saw a flash and was disoriented for a few seconds. I’ve been lightheaded and have felt a little out of it for the past few days. I’m guessing I should avoid diving for the time being; when will it be safe for me to get back in the water?

You are absolutely right to avoid diving for now. The primary concerns following a head injury are lapses in consciousness and the risk of seizures. Even a brief loss of focus can lead to a loss of buoyancy control and a rapid ascent with potentially dire consequences such as pulmonary barotrauma or arterial gas embolism. Seizures underwater can cause loss of the regulator, loss of airway control and, ultimately, drowning. Seizures that occur out of the water are typically transient and manageable events; seizures that occur underwater are typically fatal.

The Brain Injury Association of America classifies concussion (brain injury) as follows:

Grade 1 Concussion (mild)

- Person is confused but remains conscious.

- Signs: Temporary confusion, inability to think clearly, difficulty following directions

- Time: Symptoms clear within 15 minutes.

Grade 2 Concussion (moderate)

- Person remains conscious, but develops amnesia.

- Signs: Similar to Grade 1

- Time: Symptoms last more than 15 minutes.

Grade 3 Concussion (severe)

- Person loses consciousness.

- Signs: Noticeable disruption of brain function exhibited in physical, cognitive and behavioral ways

- Time: Unconsciousness lasts for seconds or minutes.

The potential for returning to diving varies based on the severity of the injury. Doctors trained in dive medicine generally recommend the following periods for returning to diving after recovery from a head injury:

- Mild: 30 days out of the water

- Moderate: 1 year out of the water

- Severe: 3 years out of the water

Please note that the clock starts not with the initial injury, but at the time you become symptom-free. If you are still experiencing symptoms of a head injury such as headaches, seizures, periods of amnesia or any other symptoms, the waiting period has not yet begun.

These recommendations are all general guidelines; you should be evaluated by a physician trained in dive medicine before considering a return to scuba diving — for your own safety as well as others’. Remember, diving is a buddy sport, and any event that occurs underwater also affects your buddy, other members of the dive group and potential rescuers.

Please feel free to contact us at +1-919-684-2948 for further questions, and encourage your doctor or neurologist to do so as well.

— Frances Smith, EMT-P, DMT

Alert Diver © Q4 Fall 2015