A maritime landscape

Beneath the ocean waves, our underwater history provides evidence of events and people that have contributed to our maritime landscape. Research on submerged sites is an ever-evolving frontier where discoveries continue to happen in places previously unknown to maritime historians. Diving in the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary (FKNMS) is an exceptional experience that offers a glimpse of many wonders: reef-building corals, 6,000 marine species, and more than 800 historical sites.

Hurricane Alley

Hurricanes have played a significant role in Florida’s underwater historical record. Scattered along the more than 150 miles (241 kilometers) of Florida Keys reef are remnants of numerous vessels lost to nature’s fury. In two instances, storms consumed multiple ships from the same fleet. Some of the earliest Florida Keys shipwrecks are from the 1622 Spanish fleet that wrecked off Key West and included the Nuestra Señora de Atocha and Santa Margarita.

Spain’s steadfast oceanic explorations continued to reach far beyond Europe for centuries. Spanish ships sailed in organized fleets to defend themselves against attack, with armed vessels to protect and escort merchant ships returning to Spain with precious materials. A second disaster involved 13 vessels from the 1733 Spanish plate fleet — named for the silver (plata), gold, and other treasures they carried — that wrecked along 80 miles of Keys coastline.

The most visited of those wrecks, the San Pedro, rests in 18 feet (5.5 meters) of water about 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) south of Indian Key near present-day Islamorada. Designated in 1988 as a Florida Underwater Archaeological Preserve to guard the rich heritage of early exploration, the site offers mooring buoys that protect the shipwreck while also providing easy access for visitors. If you want to take a dive and soak in the experience of seeing one or all of the 1733 shipwrecks, visit the Spanish Galleon Trail website at info.flheritage.com/galleon-trail.

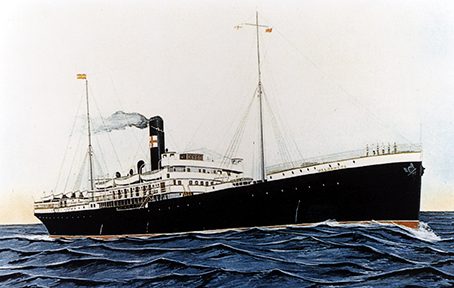

Florida’s history with Spain is vastly intertwined in other ways, as evidenced by the shipwreck of the 400-foot (122-meter) steamer Valbanera. On a 1919 voyage from Spain to Cuba, the ship encountered a rapidly forming hurricane and was turned away from Havana Harbor. The captain tried to outrun the storm, but the ship slammed into a sandy bank nearly 30 miles (48 kilometers) west off Key West in the Gulf of Mexico. None of the Valbanera’s 488 passengers and crew survived, making it the deadliest known shipwreck in the Florida Keys. In 2021, under a NOAA Ocean Exploration grant, staff from FKNMS and the University of Miami investigated the shipwreck. Learn more about this project at oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/21quicksands/welcome.html.

Divers peer through the remains of the protective arch over the drive shaft pedestal on the City of Washington.

Salvaging Wrecks

In the United States’ early years, the Keys had enough shipwrecks to support an entire industry. Wreckers assisted vessels in distress — for a price. Their efforts focused on saving the ship, crew, and cargo, and Key West became one of the wealthiest cities per capita in America. With the installation of navigational aids in the mid-1800s, the number of ships that wrecked at sea diminished, and the wrecking industry began a slow decline. Remnants of our early navigation history — lost vessels, unlit navigation beacons, and six offshore reef lighthouses — are left behind in sanctuary waters. Learn more at floridakeys.noaa.gov/historic-navigation-aids/welcome.html.

The Pennsylvania-built, 300-foot (91-meter) steamship City of Washington (1877-1910), lost on Key Largo’s Elbow Reef, is an example of an American ship with a distinguishing moment in history. While anchored in Havana Harbor, Cuba, the City of Washington was the first to assist survivors of the USS Maine after that ship suffered an explosion on Feb. 15, 1898, while moored in Havana. The Maine was stationed in Cuba to oversee U.S. interests during the Cuban war of independence from Spain. The explosion and loss of American lives contributed to the onset of the Spanish-American War two months later. The City of Washington was among several steamships the Army chartered to carry troops and supplies throughout the war. By August 1898, the war was over, and the City of Washington returned to its regular duties.

The ship’s history is steeped in details of people, places, and events. Builder John Roach was 16 years old when he came to America from Ireland in 1832. Completely alone and uneducated, he found a job with Howell Ironworks in Monmouth, New Jersey, where he learned how to work with iron. In 1871 Roach purchased a shipyard on the Delaware River in Chester, Pennsylvania, and named it John Roach and Son Shipyard. Throughout its operation, Roach and Son built 67 ships, including the City of Washington.

New technology, such as orthomosaics and 3D models, gives a new dimension to learning about shipwrecks such as the City of Washington. For more information about the wreck, see floridakeys.noaa.gov/shipwrecktrail/cityofwashington.html.

Military Influence

Life below the sea is a confluence of natural and historical significance, and ships with military involvement in service of our country quietly hold their stories of civil and international unrest. Among them is a wooden-hulled, barkentine-rigged screw steamer originally named Tonawanda. Shortly after the vessel launched in 1863, the Union purchased the Tonawanda, renamed it USS Arkansas, and assigned it to the West Gulf Blockading Squadron during the U.S. Civil War. The Arkansas name is originally from a word used by the Quapaw Nation. Following the Civil War, four additional naval vessels had the name: the USS Arkansas/BM-7, USS Arkansas/BB-33, USS Arkansas/CGN-41, and USS Arkansas/SSN-800.

The Civil War Arkansas relayed communications and carried supplies to Union warships. In September 1864 the Arkansas intercepted the vessel Watchful heading to New Orleans and claiming to need repairs. The vessel’s cargo was reported as lumber and petroleum, but a thorough examination revealed crates of hidden weaponry, and the Arkansas seized the vessel. After the Confederacy collapsed, the Arkansas was sold to private hands in 1865 and served as a coastal merchant ship. The vessel was lost on Elbow Reef in 1866 while in transit through the Keys, and its remains are now home to a bountiful abundance of sea life. Known locally as the Civil War wreck, the remains of the Arkansas along with the City of Washington and hundreds of other vessels are recognized under NOAA’s Office of National Marine Sanctuaries for their historical importance and afforded protection under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act.

Lesser-known shipwrecks, while not typical dive destinations, also contribute to the fabric of Florida Keys maritime history. The 186-foot (57-meter) Thiorva was built in 1876 in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia, under the ownership of James W. Carmichael, son of the town’s founder. Carmichael eventually took over his father’s businesses and later built ships with his uncle, George Rogers McKenzie. Norwegian interests owned the Thiorva and used it to carry timber from Pensacola to Germany. It was badly damaged when it struck a reef off Key Largo on Sept. 29, 1894. Wreckers who came to assist the damaged ship were able to save only the cargo.

The Charles W. Baird, a more modern wreck off Key Largo, was a schooner barge built in 1919 that hauled coal in Wilmington, Delaware, before a new owner, Capt. Tom Newman, relocated it to Miami. The vessel later was a floating fishing camp. A hurricane moved it to its current location, and eventually careless visitors burned it to the waterline. Locally known as Captain Tom’s wreck, the once emergent site is now slightly below the waterline and is a haven for soft coral and schools of minnows and reef fish.

Every shipwreck story has a beginning, a middle, and an end. Divers can embrace the entire history by learning about the wrecks before making their giant stride.

Enjoy history whenever you visit, and respect these sites by leaving them undisturbed for the enjoyment of others.

Explore More

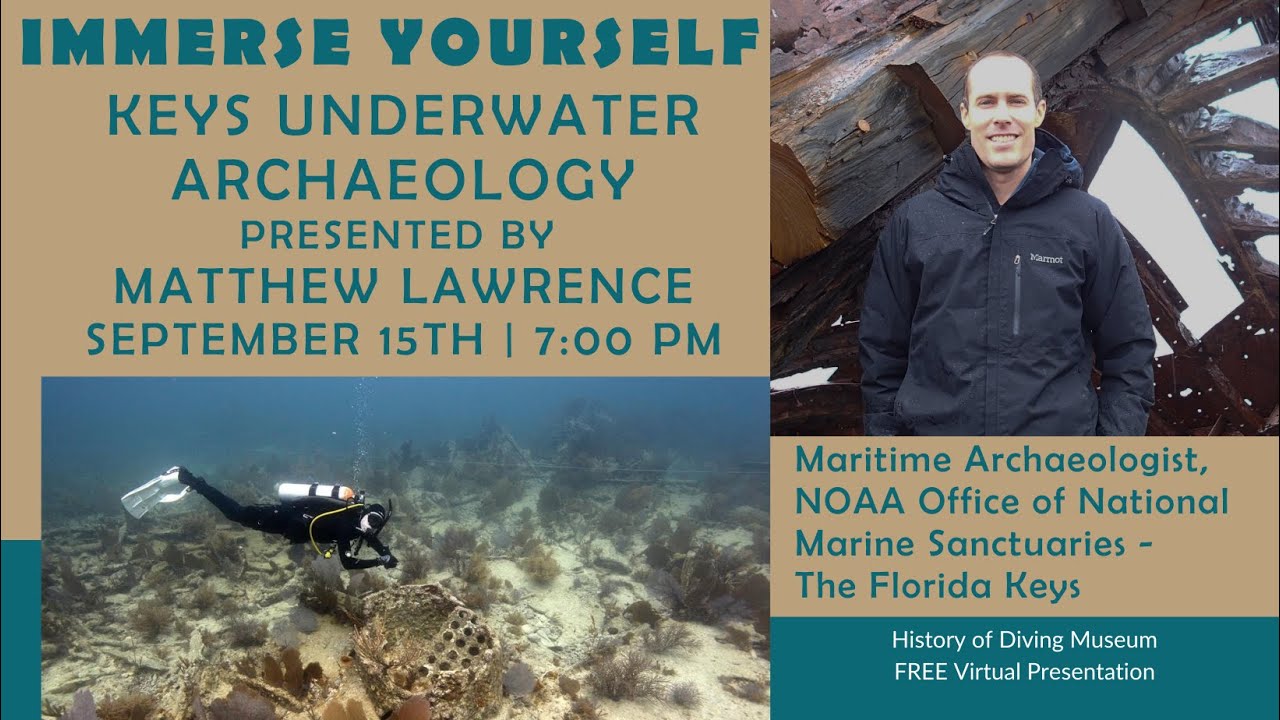

See Stephen Frink’s bonus photo gallery of Florida Keys wrecks and artificial reefs, and then watch this video of Matthew Lawrence, maritime archeologist for the NOAA Office of Marine Sanctuaries, discuss his investigations and how the public can experience these wrecks or participate in research.