DIVING IN TOBAGO is defined by the abundance and diversity of marine life in its surrounding waters. Tobago, one of the two islands comprising the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, is about 30 miles long and more than 10 miles across at the widest point. It is geographically unique because of its location where the Atlantic Ocean meets the Caribbean Sea.

The island is north of Venezuela and near where the mouth of the 1,400-mile Orinoco River converges with the nutrient-rich waters carried by the Guiana Current, which sweeps up along South America’s northeastern coast. This location plays a significant role in shaping Tobago’s marine environment. The Atlantic Ocean also brings various oceanic species, and the mixing of Atlantic and Caribbean waters contribute to the unique and diverse marine life around Tobago.

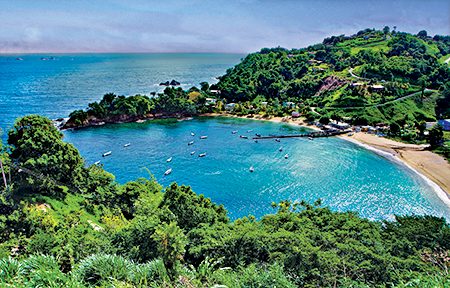

We flew from Miami, Florida, to Piarco International Airport in Trinidad, and then took a 20-minute Caribbean Airways flight to A.N.R. Robinson International Airport in Crown Point, Tobago. We had prearranged for a driver to take us directly to Speyside at the northeast end of Tobago. The village faces the Atlantic Ocean in Tyrrel’s Bay, just south of the island’s northeast tip.

The next morning we grabbed our gear, boarded a dive boat, and headed for the London Bridge dive site next to St. Giles Island. When I asked the dive operator what we should expect on the first dive, he replied that although we were no longer in the dry season, the water looked quite blue with good visibility. He added with a chuckle that diving in Tobago is always “predictably unpredictable.”

The island’s two faces — the Atlantic and Caribbean sides — offer remarkably different dive experiences. You can expect to drift dive along the Atlantic coastline, while current is almost nonexistent at the Caribbean sites.

London Bridge is an advanced dive site with a natural arch that sits above the water and resembles its namesake. There are almost no moorings in Tobago, so all dives start with a backroll entry from a live boat. Once underwater, we discovered a deep but narrow passageway running directly under the arch. We entered the passage at about 50 feet and proceeded through the narrow canyon. The vertical walls displayed a few purple sea fans and several unique, pure-white sponges.

We exited the canyon and discovered an area with huge boulders, overhangs, and crevices in depths from 50 to 80 feet. Purple deepwater gorgonians, colorful sponges, and beautiful orange cup corals adorned the faces of the boulders and the rocky surfaces of the surrounding mini walls. Schools of silversides swarmed around us as we passed through the crowds of reef fish, and several large nurse sharks were parked on the sand inside a few of the overhangs.

The following day we headed to Japanese Gardens for a relatively slow drift dive along the fringing reef to the south of Goat Island at the mouth of Tyrrel’s Bay. Our dive was at 35 to 65 feet along a steeply sloping reef. In just one day the water had turned from blue to grayish green, and the visibility had decreased overnight but was still pretty good.

The current pushed us past a beautiful landscape of brightly colored tube sponges, large barrel sponges, sea fans, sea plumes, and sea rods. The reef was alive with colorful reef fish, including pairs of angelfish, parrotfish, boxfish, Atlantic spadefish, and schools of black durgons and creole wrasses. We were amazed as a 7-foot green moray joined our group during the drift and glided effortlessly with us along the reef contours for about 10 minutes, stopping occasionally to pose for photos.

Bookends, a site just south of Tyrrel’s Bay near Speyside, features two large rocks visible at the surface with a horizontal gap between them. We swam gingerly between the rocks and found a froth of swirling bubbles. Five or six large tarpons were slowly swimming in and out of the foam and bubbles near the surface, daring us to approach them for photos as they swam effortlessly despite the strong current.

On the backside of Goat Island we discovered a terrific night dive site at 40 to 65 feet on a steeply sloping reef. Our lights illuminated one subject after another as we swam. Fish that are normally very evasive and difficult to photograph — such as scrawled filefish, honeycomb cowfish, and smooth trunkfish — were almost cooperative at this site. We also encountered sculptured slipper lobsters, spiny lobsters, and large channel clinging crabs strolling around in the sandy areas as ocean triggerfish and jacks crisscrossed through the water column.

A visit to Tobago’s Atlantic end would not be complete without going to Kelleston Drain to see what is billed as the largest brain coral in the world. We rolled into the greenish water and found a steady but not overpowering current. The drift started with an escort of several giant porcupinefish, pairs of large angelfish, butterflyfish, and small schools of creole wrasses and black durgons.

We could not miss the brain coral perched at the top of a sandy, cluttered slope in about 60 feet of water. It was indeed massive, measuring about 16.5 feet in diameter and some 10 feet high. My dive buddy posed for a couple of shots next to the brain coral to show the relative size, and yes, I was impressed.

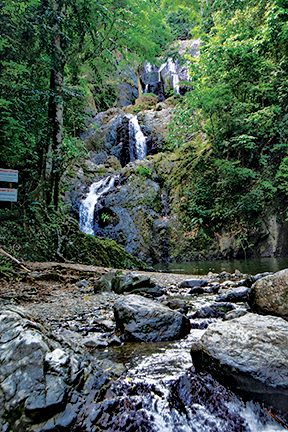

A day off from diving allowed us to explore a few topside activities in Tobago. Argyle Waterfall is a spectacular sight at 175 feet high with three dramatic main levels and an 18-foot-deep pool at its base, which was the perfect place to cool off. We devoted the afternoon to a hike through a section of the Main Ridge rainforest, one of the oldest protected forest reserves in the world. After our hike we crossed the island to the Caribbean side and drove southwest along the scenic coast, enjoying the stunning bays and beaches, including Parlatuvier Bay, Englishman’s Bay, and Castara Bay.

Crown Point, near the southwest end of Tobago, was our next base of operations. The dive operators can go from here to dive sites on the Atlantic or Caribbean side. Our first destination on the Atlantic side was a drift dive at Cove Ledge, which gets its name from the abundant cracks and overhangs that shape the reef. We kept to one side for much of the dive, exploring the sandy spaces beneath the overhangs.

The persistent current pushed us from subject to subject, which included sizeable French angelfish, pairs of white-spotted filefish, nurse sharks, and a large green moray stretched out on the sand. A hawksbill turtle happened by but appeared to be startled by our appearance. The reef boasted endless forests of soft corals, brightly colored tube sponges, and the ever-present misshapen barrel sponges, which seemed to thrive where the currents brought massive amounts of nutrients. Although there was a steady, moderate current, this site seemed quite appropriate for beginning to intermediate divers.

Our second dive on the Atlantic side was at Flying Reef, which sits about a mile offshore from the Crown Point airport. The reef surface sits at about 50 feet and has raised areas and low points, perhaps carved by the prevailing current. Sea fans, sea plumes, sea rods, coral heads, and a mix of large sponges cover the reef. The current here was strong enough to bend some soft corals, which had small schools of bar jacks and grunts hidden underneath. Many other small schools of fish, including chubs, creole wrasses, and blue chromis, randomly flitted about the reef, trying to hide from the current. As we glided along, we observed many porcupine puffers, angelfish, and parrots scattered nearby.

For our first dive on the Caribbean side, we headed southwest to the wreck of the M.V. Maverick, which was once a ferry operating between Trinidad and Tobago. The wreck now sits upright on a flat, sandy bottom at about 100 feet, providing a refuge to many reef fish and other marine life. This site is one of the few with mooring buoys. The first thing I noticed as we began our descent to the bow was that the water was eerily calm, which reminded me of the differences between the island’s two sides. There was no current. The visibility was limited on this day to no more than about 50 feet.

Schools of silversides flowed back and forth just above the wreck. Because it sits in the middle of a wide expanse of sand, the wreck has become a refuge for a variety of marine life. There has been plenty of time since it was purposely sunk in 1997 for sponges and corals to grow on the superstructure and much of the hull, which now have a thick covering of purple deepwater sea fans. Divers can move freely through portions of the interior, which had their hazardous obstructions removed before sinking. Be careful not to stir up additional silt, and pay attention to your time and depth at this fairly deep site.

Our next dive was at Mount Irvine Wall, which extends from the rocky shoreline near Mount Irvine Bay on the Caribbean side. The wall is at 18 to 45 feet deep and has several cuts or narrow channels that slice through parts of it. One channel has a long, low cave to one side that was full of schools of glassy sweepers cruising back and forth just inside the openings. As we followed the wall, keeping the rocks on our left shoulder, the topography became more of a sloping reef.

The diversity of marine life here simply blew us away. Colorful encrusting corals, sponges, and a scattering of Christmas tree worms and feather duster worms covered the surfaces of these rocky slopes. At this one reef we saw a large orange seahorse, a shortnose batfish, several pairs of juvenile spotted drums, three Caribbean reef octopuses, banded coral shrimp, arrow crabs, several moray eels, and a mix of beautiful reef fish. Except for some surge in the shallows above 20 feet, the entire area was utterly calm and offered photographers and videographers a treasure trove of subjects.

Before returning to Mount Irvine, we did a shallow night dive at the beach in nearby Store Bay. I had an incredible encounter in less than 15 feet of water just minutes into the dive. I was slowly moving my light back and forth along the bottom when something fluttered by my face mask. As I turned, my light settled on a fantastic creature that I later tentatively identified as an Atlantic mottled sea hare. It alternated between swimming through the water like a Spanish dancer nudibranch and gliding on the sand. Later, a giant porcupinefish swam up for a photo, and a giant puffer appeared in front of my camera over and over again as if it was enjoying the flash.

We insisted on returning for another look at Mount Irvine, which was just as enthralling as our first visit. Several other interesting dive sites are further up the north shore on the Caribbean side. Arnos Vale is beautiful, with depths between 20 and 65 feet and a plethora of small creatures, such as stingrays, barracudas, moray eels, and the occasional sea turtle.

It is no wonder that Tobago is known for its rich marine biodiversity. Divers can expect to encounter colorful coral reefs, incredible numbers of sponges, forests of soft corals, and an array of tropical fish such as parrotfish, angelfish, butterflyfish, and filefish. You can also watch for larger creatures such as sea turtles, nurse sharks, green morays, and stingrays.

While you may not always encounter mantas and other large pelagics, the variety and abundance of marine life you will definitely encounter along both faces of Tobago is simply amazing. AD

How to Dive It

Getting there: American Airlines, British Airways, Caribbean Airlines, JetBlue, Qatar Airways, and United Airlines fly nonstop from Miami, Florida, to Piarco International Airport (POS) near Port of Spain, Trinidad. Caribbean Airlines is currently the only airline flying nonstop from the United States to Tobago, which they do seasonally from John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. Caribbean Airlines has regular flights from Piarco International Airport to A.N.R. Robinson International Airport (TAB) in Crown Point, Tobago.

Conditions: Tobago has two seasons: the dry season (December to May) and the rainy season (June to November). During the dry season, the weather is generally more stable, with lower chances of rain and wind, and the quality of diving is more consistent. The converse is true during the rainy season, but there can be periods with calmer seas.

The average water temperatures have some seasonal variation. It’s usually warmest from July through November, averaging 82°F to 84°F. The coolest water temperatures are usually from January through April, when it dips to 79°F. The air temperatures are generally in the 80s°F during the day and the low 70s°F at night year-round.

Explore More

Learn more about diving at Tobago at visittobago.gov.tt/eco-adventure-nature/diving-tobago and see more of its wonders in the bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2023