Middle Ear Barotrauma on Ascent, or Reverse Squeeze

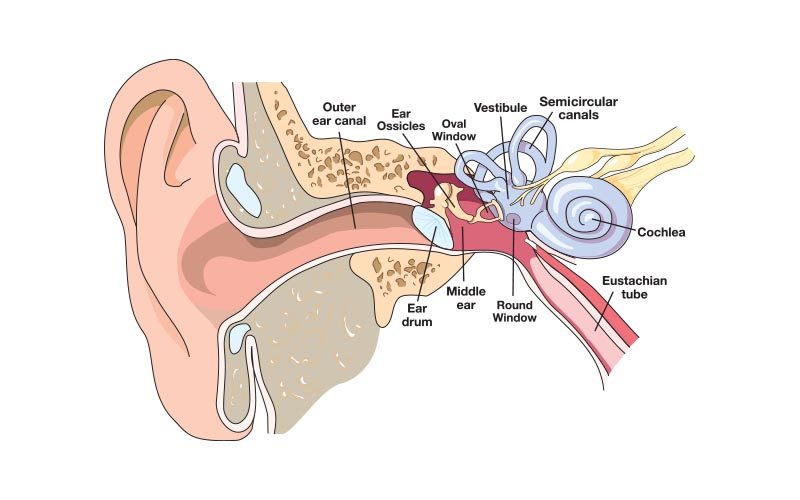

What happens: Pressure must be released from your middle ear as you ascend, or the expanding air will bulge and even break your eardrums. Normally, expanding air escapes down your Eustachian tubes, but if the tubes are blocked with mucus at depth (usually the result of poor equalization on descent, diving with a cold or relying on decongestants that wear off at depth), barotrauma can result.

What you feel:

- Pressure, then pain.

- Some divers also feel vertigo from the unusual pressure on their balance mechanism.

What to do: Sometimes one of the equalizing techniques used on descent will clear your ears on ascent. Pointing the affected ear toward the bottom may help, too. Ascend as slowly as your air supply allows, remembering that the last 30 feet will be most difficult. Otherwise, you will just have to endure the pain to reach the surface.

Inner Ear Barotrauma

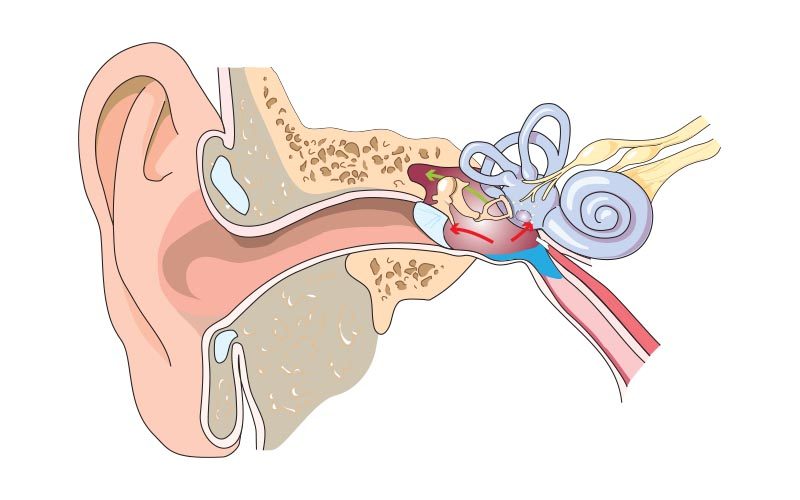

What happens: Sometimes, the stresses on your middle ear—from not equalizing or from trying too hard with a Valsalva technique—damage the adjacent inner ear hearing structures (the cochlea) and balance structures (the vestibular canals), and permanent incapacity can result.

What you feel:

- Deafness: Hearing loss can be complete, instant and permanent, but divers usually lose just the higher frequencies. The loss becomes noticeable only after a few hours. You may not be aware of the loss until you have a hearing test.

- Ringing: You may experience “tinnitus,” a ringing or hissing in your ears.

- Vertigo: The sense that the world is whirling around you, often accompanied by nausea.

What to do: Abort the dive and go as soon as possible to an ear, nose and throat specialist with experience treating divers. Inner ear injuries are tricky and require prompt, correct treatment

from a specialist.

Outer Ear Barotrauma

What happens: If your ear canal is blocked by a tight hood, a glob of wax or a non-vented ear plug, it becomes another dead air space that can’t equalize on descent. Your eardrum bulges outward, and increasing pressure in the surrounding tissues fills the canal with blood and fluid.

What you feel: It feels similar to middle ear barotrauma.

What to do: Keep your outer ear clear, which can be difficult for divers with exospores. These are hard, bony growths in the ear canal that can trap dirt and wax and even grow so big they completely block the ear canal. They are believed to be caused by repeated contact with cold water.

Prevention: Wear a hood. It will reduce the flow of water to your ears, and what does reach them will be warmer.

Can You Bend Your Ears? Yes. It’s called inner ear DCS (decompression sickness) and happens when micro bubbles form in the fluid-filled spaces of the inner ear, the cochlea and vestibular canals, following decompression. Symptoms are deafness, vertigo and tinnitus not attributable to barotrauma damage, and can occur without signs of central nervous system DCS, such as tingling and joint pain.

Bottom line: If you’ve pushed the limits, be alert for inner ear symptoms and go immediately to a specialist if you experience any problems. Barotrauma damage and DCS damage to the inner ear have similar symptoms, but the treatment is very different. Recompression, which helps when the cause is DCS, can make the problem worse when the cause is barotrauma.

Can You Dive with Barotrauma?

OK, so you messed up on your first dive of your vacation, didn’t listen to the pain in your ears, and now you’ve got middle ear barotrauma. Your ears feel “full” (they are: with blood and mucus) and you can’t hear too well.

But you feel fine, and equalizing is no longer a problem. Can you continue to dive for the rest of the week you paid so much for?

Some divers do, but they are taking a serious risk of permanent loss of hearing or, even worse, balance control. In addition to the obvious risk of infection, remember that you can’t be sure you haven’t also damaged your inner ear at the same time. Symptoms of the latter aren’t always strong or immediate. All the medical advice says that if you’ve suffered middle-ear barotrauma, get out of the water and stay out until it clears up.

For more information, pick up a copy of The Ears & Diving reference book.

Vertigo – Which Way is Up?

Vertigo, the sense that the world is spinning around you, is a common symptom of middle ear or inner ear injury. That’s because your balance mechanisms, called the vestibular canals, are located adjacent to both ear spaces. In fact, they’re considered part of your inner ears, and separated from the cochlea (the hearing structures) by the thinnest membranes in your body—two cells thick.

If vertigo happens under water, you may not be able to tell which way is up and panic. (Emergency tip: watch the water in your mask to judge your orientation and follow your bubbles, slowly, to the surface.) Additionally, vertigo is often accompanied by vomiting. Be prepared, but don’t be alarmed.

Damage to your vestibular canals, whether by DCS or by pressure shock, is usually permanent. Vertigo may go away in two to six weeks because your brain learns to compensate and ignores the side that’s damaged, but the canal will not heal. Damage the vestibular canals on the other side too, and you could be unable to drive a car, much less dive.

Vertigo can also occur from stimulation of one side and not the other—the pressure difference if only one ear equalizes or the temperature difference if cold water enters one ear but not the other. In both cases, your brain interprets unequal stimulation of your vestibular systems as movement. This type of vertigo disappears with the unequal stimulation, fortunately, and leaves no after-effects.