The newly reorganized DAN Safety Services department combines the prevention focus of our risk mitigation efforts with the incident-response aspect of our first aid courses and safety products. Everyone in the dive industry — students, divers, and dive professionals and operators — can access DAN’s wealth of educational, training and safety product options to help keep themselves and their fellow divers safe.

A DAN member shares lessons learned while lost at sea for many hours after being carried far from the dive site by currents. It’s important to stay calm and bring your own safety gear such as a surface marker buoy. Before leaving on a trip, establish good physical fitness and always let someone know where you are and when to expect you. Understand the risks, be proactive about your safety, and don’t ignore red flags about the dive operator.

Shipwrecks lure divers as much as they attract the sea life surrounding them. The spectacle of life on a wreck, an ecosystem unto itself, is often the main attraction for divers. Nearly every ocean, sea and lake holds a world of shipwreck exploration for advanced open-water divers. Each lost ship, submarine, airplane and even the odd locomotive is a time capsule waiting for an underwater explorer to visit and photograph. Never venture inside a shipwreck until you have advanced wreck-dive training from a certified, qualified dive training professional.

Our checkout dive was easy, with a maximum depth of 75 feet for 50 minutes. The current was slight, and the visibility was spectacular — an ideal first dive. It closed with a nice, slow ascent and a three-minute safety stop. When we returned to the boat, I felt a sudden tingling in my right foot followed by a dull ache in my knee. I assumed the worst, thinking I had decompression sickness (DCS). When I reviewed the dive in my mind, however, that seemed impossible.

Sometimes life gets in the way — family obligations, unforeseen injuries, work responsibilities, social events — or perhaps the world as we know it shuts down for a while. When these things overwhelm us, many people tend to sacrifice exercise first. You may miss a few workouts, and then your exercise routine slowly slips from regular to nonexistent. It happens to most people — even fitness experts and professional athletes — at some time. Although it may feel challenging, it is possible to restart your exercise routine.

Reduced exercise tolerance is common for those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and poses risks for diving. There can be strenuous activity involved with managing currents, swimming on the surface in choppy seas or pulling yourself and your heavy gear up a ladder and onto an unsteady boat. With COPD, shortness of breath during exertion doesn’t mean you are out of shape; it means you cannot rid your body of carbon dioxide and replace it with the oxygen needed to meet the demand of your exertion.

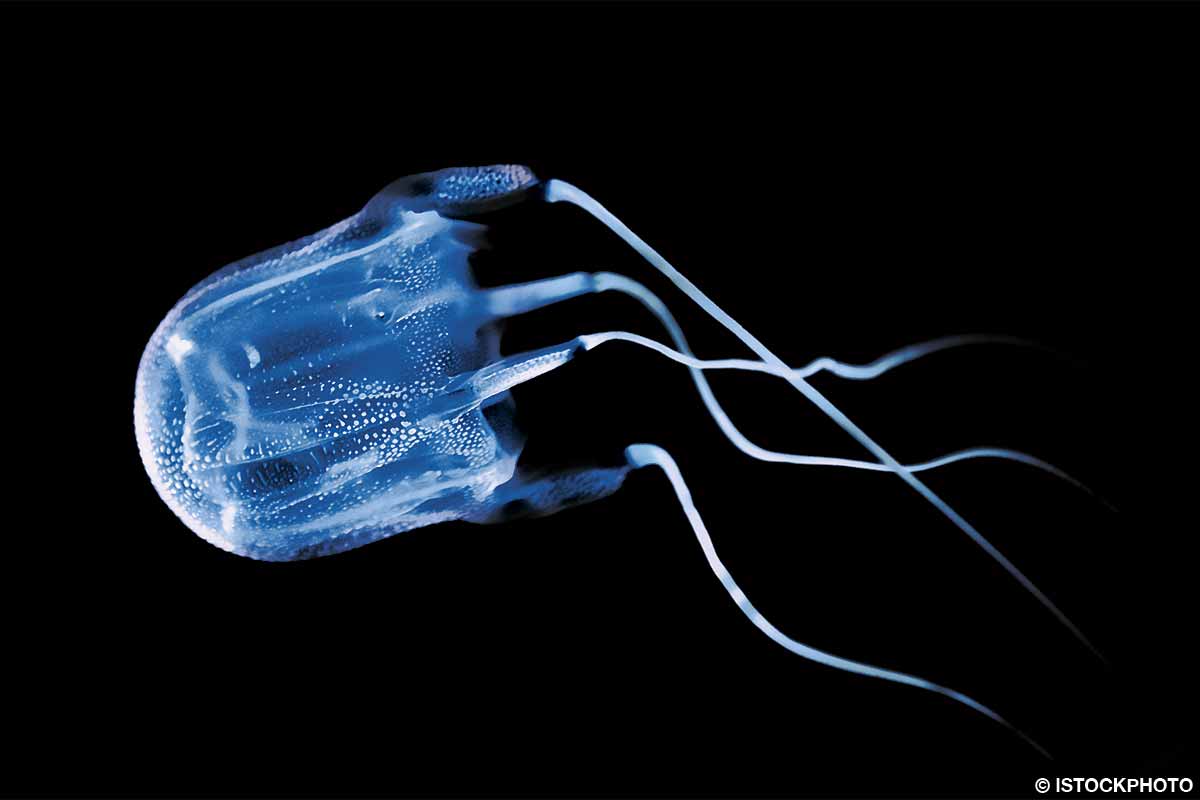

Nitrogen narcosis can lead to deadly consequences. Understanding the risk factors and ensuring that you and your dive buddies have discussed how to mitigate risk can potentially save lives. If you are stung by a jellyfish, watch for symptoms associated with Irukandji syndrome. If symptoms develop, know that it is a potentially deadly condition that doctors can help treat. Pay attention to local marine life bulletins and announcements. The best ways to mitigate jellyfish envenomation risk are to wear full exposure suits and avoid jellyfish when they are prevalent in the water.

During medical school Peter Lindholm joined a laboratory researching aviation, space and underwater physiology, where he developed a passion for breath-hold dive physiology, about which he wrote his doctoral thesis. As one of the physicians for the Swedish Sports Diving Federation (SSDF), he was involved in developing breath-hold dive protocols and training the first instructors of competitive breath-hold diving. After clinical training as a radiologist, Lindholm moved to San Diego, California, where he leads a research group focused on dive physiology and dive medicine.

The first step in ensuring the safety of staff, divers and the public is to develop a detailed awareness of the real risks present in all operations performed by dive businesses and professionals. DAN® has produced a brief guide for anyone responsible for safety. The guide offers an introduction to identifying and understanding 17 of the most common areas of concern. These potential incident sources highlight the kinds of considerations that need attention and help operators to better understand how they might apply this knowledge to their businesses.

Pulmonary barotrauma can occur in a shallow swimming pool if a diver holds their breath during ascent or inadvertently floats to the surface while holding their breath. Most dive-related pulmonary barotraumas occur in compressed-gas diving due to pulmonary overinflation during a breath-hold ascent. Pulmonary barotrauma can occur even with normal breathing if there is an obstruction in the bronchial tree that prevents one lung segment’s normal ventilation.