Q: While checking out the safety gear available on a dive boat, I noticed an automated external defibrillator (AED) among the first-aid equipment. Is it safe to use an AED around water? How about on a metal boat deck?

A: Early defibrillation and aggressive CPR are the two actions proven to increase the likelihood of survival of a victim of cardiac arrest. CPR circulates blood to vital organs, but it cannot restore a patient’s heart to a healthy rhythm. The definitive survival treatment for someone experiencing cardiac arrest is defibrillation — a shock. To be most effective, defibrillation must occur as soon as possible after the onset of cardiac arrest. According to the American Heart Association (AHA), each minute of delay before defibrillation reduces the chance of survival by 10 percent. Published studies have asserted that early defibrillation can save up to 74 percent of victims.

While AEDs have been used for many years in airports, shopping malls, gyms and senior citizens centers, divers and boat captains may be reluctant to bring them into wet environments or onto metal-hulled boats out of concern that bystanders may be endangered by potential electricity conduction. Current research, however, indicates that AEDs are safe to use around water and on metal surfaces.

The best information is available from the AED manufacturers themselves, who document minimal conduction of electricity to bystanders during defibrillation with AEDs. As long as the rescuer does not have actual contact with the victim’s chest (i.e., touching the chest to administer CPR), he or she is not at risk for significant electrical shock. Also, the longer the distance between the defibrillation pads and the bystanders, the less electricity will be transmitted. Those in a boat or on a conductive surface (metal or water) may feel, at most, a tingle.

In a statement from the AHA and other resuscitation agencies: “Always check with the manufacturer, but most AEDs, because they are self-grounded, can be safely used in wet environments and on metal surfaces with no risk to the victim or rescuer.”

— Frances Smith, EMT-P, DMT

Q: Why do the effects of decompression sickness (DCS) last longer than the 12 to 18 hours it takes to offgas? Do the bubbles that cause DCS lead to other problems in the body that last longer? If that’s the case, why are chamber dives effective in easing the symptoms of DCS even after a day or more has passed and the level of inert gas in the body is no longer elevated?

A: DCS can manifest in many ways, and the signs and symptoms depend on the body system or systems being affected. DCS usually involves large numbers of small bubbles, and their effects include mechanical tissue damage and the interruption of blood flow to some areas of the body. Irritation can occur in the endothelium (the cells lining blood vessels), which leads to inflammatory responses that may cause platelets to initiate clotting and white blood cells to accumulate. The inflammation and tissue damage take a while to heal, which is why DCS lasts longer than the time it takes to eliminate inert gas.

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) can be effective for days or even a week or more following a dive because HBOT has significant anti-inflammatory properties and oxygenates injured tissues, thereby promoting healing. HBOT is frequently administered after the tissue damage, inflammation and other injuries have occurred and no inert gas remains; in these cases its purpose is only to promote healing. However, HBOT administered very soon after the injury also promotes the washout of inert gas.

— Scott Smith, EMT-P, DMT

Q: I recently had a stapedectomy. Can I dive? What are the risks?

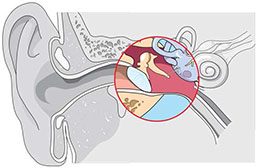

A: Ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeons trained in dive medicine differ in their opinions regarding the wisdom of diving after a stapedectomy, which is a surgery to treat hearing loss by replacing the stapes bone in the middle ear with a prosthesis. This controversy extends to diving with any ear condition that increases the risk of permanent injury. All of us who dive place our hearing at risk, and barotrauma (pressure injury) of the middle and/or inner ear increases the risk of hearing loss. While some ENT experts absolutely recommend against diving for individuals with existing ear issues, others opine that patients who understand and accept the potential risks may dive.

Limited studies have described small numbers of people diving after stapedectomies. The results from these samples indicate that the subjects are not at increased risk of injury when compared with the control groups of divers — provided they can safely equalize their ears and sinuses with the changes in ambient pressure. With that said, the consequences of failure to equalize can be greater for those who have undergone stapedectomy procedures. The inability to equalize the middle-ear space effectively or an attempt to do so too forcefully may dislocate the prosthetic stapes. Dislocation can be corrected only in surgery and may result in permanent hearing loss.

Diving after a stapedectomy also carries the risk that dislocation of the prosthesis may damage the round or oval window of the cochlea. Such an injury can permanently affect both hearing and balance. Again, it is not that the risk of injury is necessarily greater than that faced by other divers, it’s that there are greater consequences in the event of an injury.

Before deciding to pursue or return to diving, it is clearly in your best interest to candidly review your fitness to dive with a doctor and make a brutally honest risk/benefit analysis based on the information available. Contact DAN if you would like more information.

— Marty McCafferty, EMT-P, DMT

Q: I’m a beginner diver, and I have difficulty equalizing my ears. I have heard that I shouldn’t dive if I use nasal decongestants, but is it safe to dive if I use nasal steroids?

A: It is very common for new divers to experience difficulty equalizing their middle-ear spaces. As you gain experience and learn the techniques that work best for you, you will find equalization easier in general. There is little scientific data regarding any specific medication and diving, but based on the known side effects of steroid nasal sprays, there is little reason to suspect they would be problematic for divers.

Even though the fast-acting nature of decongestants can be appealing, there are several reasons why steroids may provide a safer option. Swelling and inflammation of the cells lining the Eustachian tubes, middle-ear space and sinuses may lead to occlusion and barotrauma. The mucous membranes lining these structures are vascularized, and decongestants provide a short-term solution to congestion by constricting the blood vessels in the mucous membranes, which decreases swelling. When the decongestants wear off, however, the blood vessels are no longer constricted. The aftereffect is that the blood vessels will swell and may become more engorged with blood than before, which is known as the rebound effect. Unlike decongestants, steroids do not act as vasoconstrictors, so there is no rebound.

Another disadvantage of decongestants is that they are only intended for short-term use and may lose effectiveness with habitual use. The steroid fluticasone propionate and similar medications, on the other hand, are intended to be used over substantially longer periods of time than decongestants. If you plan to use a nasal steroid, it is important to start using the medication at least a week before your dive, because it takes about this amount of time for the drug to reach maximum effectiveness. In general, nasal steroids are considered safe to use when taken as directed and may be quite effective at preventing ear barotrauma for those who have difficulty equalizing.

— Marty McCafferty, EMT-P, DMT

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2014