Bountiful biodiversity

While we were hiking in Denali, our guide scattered several small string ringlets across the tundra. For the next five minutes our task was to tally as many distinct flora as we could identify. I was astounded to have counted 28 plants in my tiny region of tundra. The density of life we could observe when pausing for closer inspection was overwhelming.

Our explorations of Belize’s equally biodiverse jungles and reef systems some 4,000 miles (6,437 kilometers) south repeatedly reminded me of that endless summer afternoon in Alaska.

With an area of 8,867 square miles (22,966 square kilometers), Belize is slightly larger than New Jersey. While the land is steeped in ancient Mayan civilization, Belize is a relatively new country. Known as British Honduras until 1973, it declared its independence from Great Britain in 1981 after 119 years under the crown.

This young, small nation has taken up a tremendous mission to protect its rich biodiversity on both land and sea. The barrier reef off Belize’s coasts is the largest in the northern hemisphere and is managed by seven connected marine protected areas that comprise the Belize Barrier Reef Reserve System, which became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

Belize is also home to three atolls, which are rings of coral surrounding a lagoon. Lighthouse Reef Atoll, for example, is the location of the famous Great Blue Hole. The coral ring is typically formed when a volcano rises above the water’s surface, and a coral reef develops around the volcanic island. When the volcano recedes, the atoll remains.

Outer Reefs

We set sail to see what these atolls and reef systems had to offer. Our first stop was Zipline in Turneffe Atoll Marine Reserve, where friendly nurse sharks swam so close you could easily see the black, white, and brown speckled patterns adorning their skin.

The sandy fields surrounding the coral were abundant with burrowing creatures. Populations of garden eels emerged, awaiting the daily arrival of zooplankton for nourishment, but they retreated into their sandy dwellings as we finned closer. Yellowhead jawfish danced above their homes, ducking in when we first approached. We gave them space and a little bit of time and were delighted when they emerged again.

We even caught a glimpse of a scaly-tailed mantis shrimp at its stoop, keeping a keen compound eye on us. Mantis shrimp have up to 16 photoreceptors compared to our mere four, meaning that these shrimp see the reefs in a way that we cannot even imagine — with the addition of ultraviolet and polarized light.

Back on the boat, we sat on the upper decks en route to Long Caye and sped past palm-tree-laden land masses as a playful pod of bottlenose dolphins leaped in the yacht’s wake. Towers of white clouds hinted at afternoon showers as the winds picked up.

Our afternoon mooring was Long Caye Ridge. The dive deck dropped us onto coral heads at 25 feet (7.6 meters), leading to fingers of sand stretching out over a drop-off. Caribbean reef sharks greeted us at the wall, while large triggerfish and schools of midnight parrotfish patrolled the coral above.

As day shifted to night, giant basket stars unfurled in an intricate lace designed to capture and consume unfortunate creatures that drift too close in the dark. Our friend’s camera lights drew in schools of synchronously swimming Caribbean squids dancing to a symphony only they knew. Tarpon lurked just offstage, opportunistically hoping to catch a squid off guard upon its exit.

Over the next few days we alternated moorings between Long Caye and Half Moon Caye, visiting Chain Wall, Quebrada, Julie’s Jungle, Long Caye Wall, Angelfish Wall, and my favorite, the Aquarium.

Chain Wall is named for the breaks in the wall that resemble chain links and create natural alcoves to explore. Strong currents pushed us toward the south wall, where Caribbean reef sharks and groupers weaved through our group. As we reached the southern drop-off, a spotted eagle ray glided by, soaring into the depths with an effortless flap of its wings.

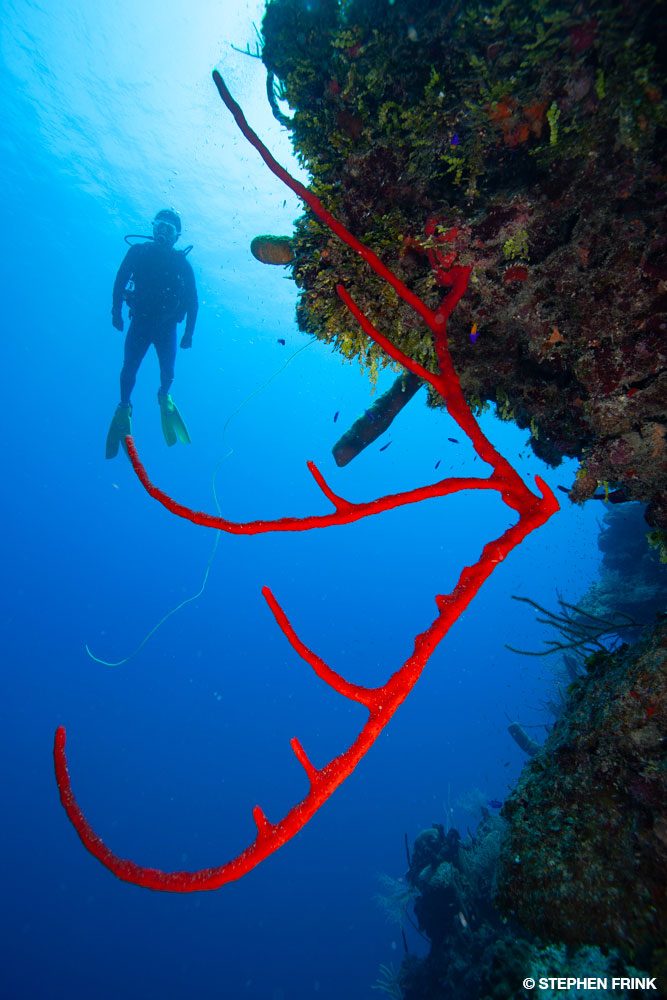

Cresting over the ridge, we emerged through one of the chain links into a shallow coral forest. Belize’s reef system is home to more than 70 species of hard corals and 36 soft corals. We closely inspected some hard corals and spied blennies peeking out from tiny holes as electric yellow and blue queen angelfish meandered through nearby sea whips.

A seemingly perturbed Caribbean reef shark was swimming in large circles toward the wall’s edge. A persistent fish chased the shark, rubbing up against the predator’s sandpaper-like skin from its tail toward its head. Researchers are still exploring this behavior, known as chafing, but it seems prevalent across multiple species of fish and sharks. Chafing appears to be another way that fish remove parasites from their skin in more of an exfoliating approach to skin care than a typical cleaning station.

As we made our way back to the boat, we were treated to sightings of all three of Belize’s common turtles: green, hawksbill, and loggerhead. Colossal schools of horse-eye jacks, grunts, and sergeant majors surrounded us beneath the boat.

Nocturnal Encounters

Our afternoon and night dives took us to Quebrada. Upon our descent into the darkness, the nightlife was ready to put on a show. A 3-foot baby nurse shark swam by as I waited for my buddy on the bottom at 35 feet (10.7 meters). We trailed after the juvenile toward the drop-off, where my light fell on a whitespotted toadfish sitting outside its rocky retreat. We were told to look for this particular fish that’s native to Belize’s offshore atolls. You typically listen for its distinctive croaking sounds or search for a glimpse of its beard beneath the rock. But tonight was special because I observed the elusive toadfish in all its glory, with its flattened head, tendrils, and spots.

As we finned away from the toadfish, a juvenile arrow squid caught my attention from about 15 feet (4.6 meters) away. I raised my light, and the small cephalopod followed the narrow beam down to my hand, giving me an intimate display of the red, gold, and black spots adorning its translucent, glassy body. After our enchanting interaction, it continued off into the darkness, and we turned our attention to a black and white spotted moray hunting a stoplight parrotfish.

When it was time to return to the surface, we switched off our lights to avoid attracting the sea wasps that like to hang out in the top 20 feet (6.1 meters) of the water column at night.

Free-Range Aquarium

Our dive at the Aquarium on Long Caye’s northwestern edge began at 30 feet (9.1 meters) with a deep drop-off to the north. Each time my eyes drifted toward the deep, it seemed I was seeing another reef shark or spotted eagle ray as I swam along the edge. One eagle ray, with markings reminiscent of cave drawings bespeckling its back and a cleaner fish latched onto its tail, took an interest in our group, looping back to swim with us for a while.

Black feather corals swayed gently like pine trees on a breezy day. Various gorgonians and giant sponges gave the reef brilliant color. Pederson cleaner shrimp and banded coral shrimp staffed cleaning stations oscillating their tentacles to advertise parasite removal and detailed mouth and gill cleanings to the passing clientele of local grunts and groupers.

Midnight parrotfish commuted past, and endless linear schools of creole wrasses that looked as though they emerged from a Vincent van Gogh painting streamed along the drop-offs in the late afternoon. These dives became even more spectacular when we spotted a large green moray eel swimming in the open and a green sea turtle sleeping soundly in the reef. It truly felt as though we had visited a meticulously curated aquarium tank containing all our favorite creatures.

The Great Blue Hole

We were uncertain whether we would be able to dive the legendary Great Blue Hole — parking a boat of our size in the 984-foot-wide (300-meter) center of Lighthouse Reef Atoll requires specific wind conditions — but thankfully the weather cooperated.

At 134 feet, our boat is nearly the size of Jacques Cousteau’s Calypso, which ventured through this same tricky terrain of coral heads in shallow waters during his famed expedition. Cousteau came to the Great Blue Hole to better understand the changes in sea levels over the past millennia. His team excavated a fallen stalactite from the site’s floor to aid that research.

We made our way to the hole’s edge and began our descent as a group into the deep blue cavern at the center of the azure waters. The Great Blue Hole is 410 feet (125 meters) deep, but we limited our depth to 135 feet (41 meters), just past the recreational dive limit.

The stalactites along the cavern walls define this profile. Our total dive time would be 30 minutes, with a quick descent to our maximum depth, where we would spend no more than eight minutes. Then we would begin a gradual ascent to 60 feet (18.3 meters), where we would continue to explore the walls for a two-minute deep stop followed by a safety stop in the shallows.

We plunged along the wall of the collapsed cave lined with green aquatic hanging vines as waterfalls of disturbed sand cascaded downward. The deeper we dived, the clearer the visibility became because of the limestone walls that comprise the structure around 90 feet (27.4 meters). At 110 feet (33.5 meters), gigantic stalactites more than 20 feet (6.1 meters) long came into view, revealing just how massive this cave must have been before it collapsed and sea levels rose.

We curved around the final stalactite at our maximum depth and began our ascent, scanning the walls for tiny bits of life residing in this famous and oft-visited dive site. After spotting some small reef fish and a lobster in a recess around 60 feet (18.3 meters), we continued up the wall and crested the lip of the hole into a field of seagrass teeming with life.

Many divers report Caribbean reef sharks and occasionally hammerheads looming in the Great Blue Hole’s hazy visibility, but unfortunately we didn’t see any sharks patrolling the waters during our brief visit there.

The most remote of Belize’s atolls, Lighthouse Reef features abundant shallow reefs, ledges, and massive drop-offs that are home to about 200 fish species. I spent my safety stop watching crabs scuttle across the sands and butterflyfish and angelfish weaving through abundant staghorn and elkhorn corals. Soon we were back on the boat, sharing stories of our experiences at this famed site.

Half Moon Caye

Next we took a shoreside visit to Half Moon Caye Natural Monument, home to a rare littoral forest crawling with hermit crabs. If you stand still, you will see the ground moving slowly and in shells.

One reason for the protection status is the large nesting colony of the rare white-phase red-footed booby that resides in the ziricote trees. A short trail from shore leads to a bird tower, where researchers can observe and study the island’s booby populations as well as see magnificent frigate birds soaring above. The island is also a turtle nesting ground and home to the historic lighthouse from which Lighthouse Atoll takes its name.

The reef wall that borders Half Moon Caye features an astounding 3,000-foot (914-meter) drop-off. We explored Angelfish Wall, named for the gray angelfish living along the site. This dive features a variety of terrain with a deep, south-facing drop-off, a shallow reef bed at 35 feet (10.7 meters), and turtle grasses to the north.

The seagrass features a surprising abundance of life. Several mounds of white sand begged to be overlooked, but we couldn’t ignore the eyes that followed us and the steady opening and closing of gills with each breath. We then paused to watch southern stingrays flit their wings and take flight from the seafloor.

Venturing farther into the seagrass, we found queen conchs mating and laying eggs. The 2- to 3-inch (5- to 7.6-centimeter) sticky secretions the females deposit can contain up to half a million eggs. The sand beneath the seagrass binds to the sticky egg deposits and camouflages them from predators. Near the conchs in the meadows, we found large queen triggerfish and hogfish, which are conch predators.

Returning to Port

Our final dives took us back to Turneffe Caye, where we explored Amberhead South. We set out for a double dip in the early morning and watched as the reef started to awaken. A sleepy porcupinefish emerged from a boulder coral, rubbing its eyes and wondering why I was disturbing its slumber. I followed it for a few minutes as it dawdled around the reef.

Distracted by queen and gray angelfish sightings, we continued while pushing against a strong current. We spotted a massive free-swimming remora off in the blue and scanned the surroundings to see if it had recently been paired with a host. We continued along the site, enjoying the rich variety of corals as we exhaled our final breaths beneath the Caribbean Sea.

Belize has more than 400 islands and cayes. If you are not diving from a liveaboard, you can access many of the sites mentioned here with day boats from Caye Caulker and Ambergris Caye. From these cayes you can also easily visit the Hol Chan Marine Reserve, which has been a protected area since 1987 and is Belize’s oldest marine reserve. It is divided into four zones: the reef, seagrass beds, mangroves, and Shark Ray Alley. The reef and Shark Ray Alley are popular dive areas with excellent visibility and abundant life.

Surface Interval

From birding tours, cave tubing, and jungle ventures to historical Mayan sites, Belize has much to offer for topside exploration. During one surface interval we visited Caracol deep in the Chiquibul Forest Reserve. The largest Mayan site in Belize, covering more than 77 square miles (200 square kilometers), the Caracol area was occupied from as early as 1200 B.C.E. until 950 C.E. It was once home to more than 100,000 Mayans — larger than the current population of Belize City. For perspective, the famed Incan site of Machu Picchu is estimated to have supported 750 people at most.

Excavations unveiled massive pyramids, monuments, tombs, a ball court for ritual games, and an astronomical observatory called the Temple of the Wooden Lintel. From the top of the main temple, Canaa, you can see the dense jungle that spans the former city and neighboring Guatemala. To cool off after a hot afternoon in the jungle, stop at one of the many waterfalls and pools, such as Rio on the River or Big Rock Falls.

You can combine caving and watersports with cave tubing tours about an hour from Belize City. A short hike through the jungle leads you to Nohoch Che’en Cave, where you can explore a cave system from the comfort of a floating tube.

How To Dive It

Getting there: Fly into the Philip Goldson International Airport in Belize City. U.S. citizens are not required to have a visa for stays of 30 days or less. You can pay marine park fees through your tour operator.

Conditions: Water temperatures are fairly consistent year-round, usually ranging from 78°F to 82°F (25.5°C to 27.8°C). Belize is a subtropical climate with air temperatures ranging from the mid-70s°F to the mid-80s°F (about 24°C to 29°C) on average. Visibility ranges from 45 feet (13.7 meters) to more than 100 feet (30 meters). The dry season is from December to May, and the rainy season is from June to November.

Explore More

See more of Belize in this photo gallery and video.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2024