I rarely know as little about a destination before embarking on a liveaboard charter as I knew about Borneo. I had been to Borneo before, but it was after a dive trip to Malaysia, and I only spent time topside to photograph orangutans.

I didn’t know that Borneo is the world’s third-largest island; only Greenland and New Guinea are larger than Borneo’s 288,869 square miles (748,168 square kilometers). Indonesia governs most of the island, calling it Kalimantan, but Malaysia and Brunei share ownership. The island is squarely situated in Indonesia’s Coral Triangle, so I decided to give it a try, and I’m glad I did.

Liveaboards in Indonesia tend to follow seasonal patterns for their destinations. There’s an ideal time to be in Raja Ampat, which won’t necessarily be the same time you might choose to cruise the Forgotten Islands, Triton Bay, or Komodo. Indonesia is a vast country: It’s the world’s largest archipelago, with 17,000 islands spread across 735,000 square miles (1,904,000 sq km).

My research showed that May through September is the best time for a dive cruise in Borneo from the gateway port in Tarakan and that the water temperature in late August would be 84°F (29°C). We carved out an itinerary that included a few days in Bali to acclimate to the time zone and do a little topside touring. A domestic flight took us from there to Tarakan via Surabaya.

I had imagined Tarakan as a sleepy tropical village, but I discovered that it is actually a bustling city and an island. Located in the province of North Kalimantan, Tarakan has a modern airport and a population exceeding 250,000. While it is not a dive destination, it is a springboard to numerous dive sites scattered throughout the Derawan Archipelago and East Borneo. You can dive from land-based resorts throughout the islands, but we chose to experience Borneo by liveaboard.

We arrived at the port in the early evening and looked out at a wide variety of pleasure yachts and freighters dotting the horizon. Only our boat had the look of a liveaboard, which is quite different from other Indonesian ports such as Sorong, where more than a dozen dive vessels might be in port and as many as 50 operating throughout Raja Ampat during the high season. Komodo likewise will have 50 or more liveaboards plying those waters. We never saw another liveaboard or even a day dive boat during our week at sea. That alone is a significant differentiator for the Borneo experience.

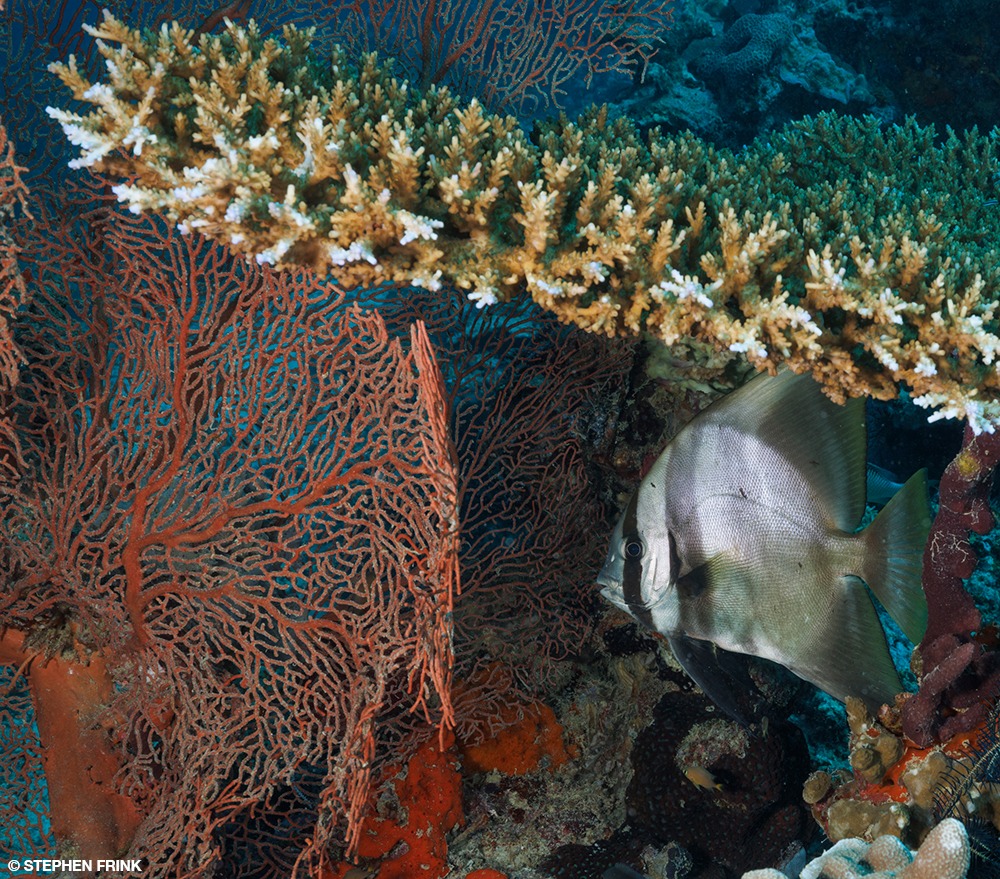

Coral was the other differentiator. Vast fields of staghorn and other species of antler coral were prolific on many of the reefs we visited. That sight is not entirely uncommon throughout Indonesia and places such as Tubbataha in the Philippines, but the density and diversity of the coral cover along the Borneo shallow reef is unique. It is a special privilege to see such pristine coral forests, especially when we have lost coral in so many places around the world due to global warming and stony coral tissue loss disease. Knowing what we have lost makes me especially appreciate what remains, and each dive in Borneo was inspirational in that regard.

We began the trip with a somewhat underwhelming dive following the overnight crossing to Sangalaki. Coral Highway was a little disappointing, mostly because I was shooting wide-angle, and the only significant subject was a cooperative broadclub cuttlefish. Those who chose macro raved about their fire dartfish, emperor shrimp, and whip coral shrimp.

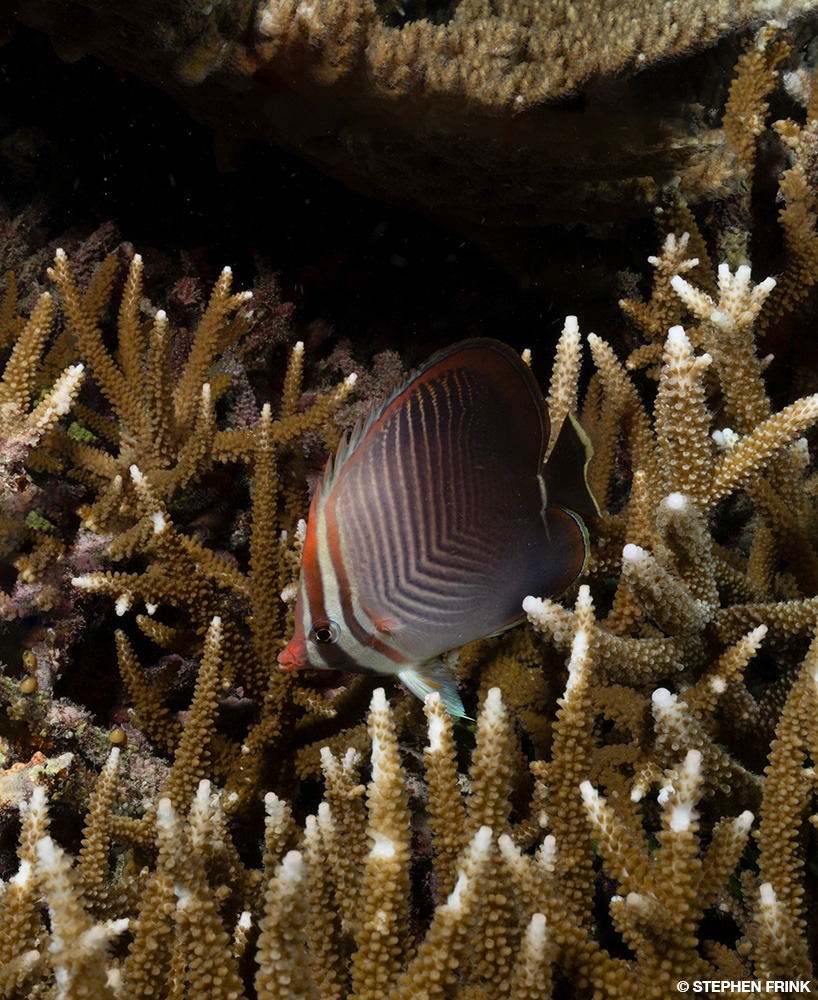

That dichotomy — wide-angle versus macro — held throughout the trip. It was like being on totally separate reefs, depending on the lens. The wide-angle imaging was so compelling that I mounted my 100mm macro lens only twice: once on a night dive and the other at the end of the trip, allowing me to concentrate on the myriad small angelfish and butterflyfish that are specially adapted to feeding in the hard corals.

I collaborated with my friend Jan Andrews, who handled the macro shooting and shared a few of her photos for this article. Her vision of Borneo through a 100mm lens was decidedly different from mine through a 15-35mm or 8-15mm fisheye lens. While Jan realized she would miss the wide-angle pelagics, schooling fish, and coral vistas, she maintained her devotion to hunting and photographing small critters.

“The corals were pristine with impressive specimens of staghorn and lettuce corals covering many sites,” Jan said. “Sometimes the sheer density of coral cover made macro difficult because you have to be diligent with your buoyancy to avoid bumping into fragile coral. But with a careful approach camouflaged amid this exciting substrate is a thriving world of macro species.

“It was essential to build a rapport with the guides, who with their expertise enthusiastically helped me in my critter-finding efforts,” she explained. “At most sites we were able to spot a diversity of macro life, including colorful nudibranchs, crabs, coral shrimps, blennies, and gobies. In the shallows hiding amid the coral colonies we found a variety of interesting small reef fish, including juveniles. While Borneo may not be the ideal location for an exclusively macro quest or as famous as other muck locations throughout Indonesia and the Philippines, the diversity was impressive and the frequent photo opportunities certainly did not disappoint.”

Our dives at Sangalaki would have been more productive if I had concentrated on critters. The list that my buddies came home with from Sangalaki Slope and Sangalaki North included yellow maskangelfish, pinnate batfish, fusiliers, schools of pyramid butterflyfish, bluespotted ribbontail rays, and turtles. Turtles became a Borneo staple for us. One dive later in the week had as many as 20 turtle sightings. While I had a good time, my fellow critter hunters were more richly rewarded.

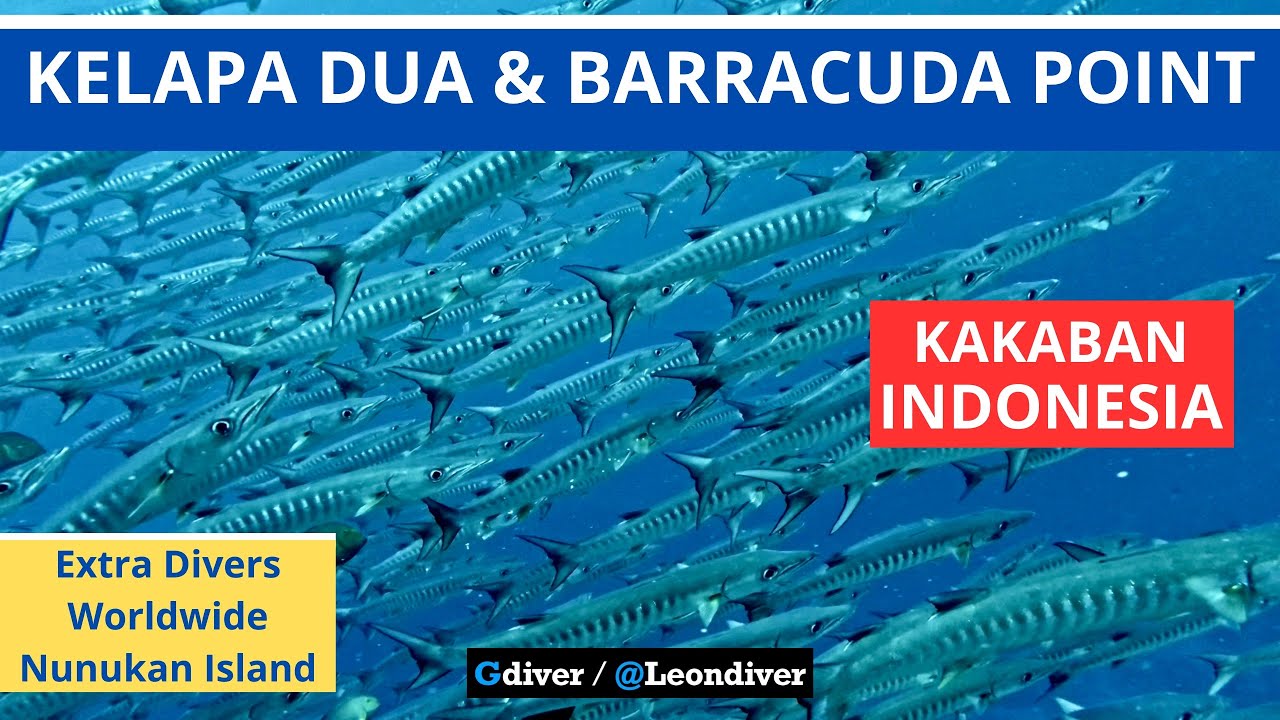

My first extraordinarily productive day came the next morning as we dived Kelapa Dua. This coral garden will go down in my memory card as one of the best of the best. It helped that it was a slick, calm day, so the water’s surface became a mirror reflecting the immense fields of staghorn corals just below the surface. One of the cruise directors agreed to dive with me that morning, swapping off duties as dive model, snorkel model, and behind-the-scenes photo documentarian.

One time she even saved me from stranding. I was working along a very shallow zone of coral punctuated by a single barren rocky plateau. I could float above the rock to work on some over/under views, insulating me from the possibility of bumping into living coral. In the 15 minutes I was in place, however, the tide receded enough so it would be difficult to leave the same way I swam in.

She relieved me from the burden of carrying my camera, and I was able to find a navigable escape route that would not impact coral. Another 15 minutes later that path would have been gone as well. The difference between high tide and low tide can be as much as 6.5 feet (2 meters), leaving many of these corals exposed at low tide.

Like several other dive sites during the week, the deeper portions of the reef were intriguing. We found larger reef denizens, such as bluefin trevallies, dogtooth tunas, and hawksbill and green sea turtles, while our macro enthusiasts concentrated on two-tone dartfish and crinoid shrimp. We rarely dived deeper than 80 feet (24 m) and spent the last 30 minutes of most dives above 30 feet (9 m), making these very safe multilevel dives. It is best to use caution to try to prevent any dive injuries because Borneo is indeed remote.

The second day at Kelapa Dua we dived an excellent vertical drop-off at Mataha Wall. Borneo is curiously short on soft corals, but I found a few nicely decorated clusters of Dendronephthya hemprichi along the wall. Black coral and large sea fans were common, especially as we dropped below 60 feet (18 m), but these are not the colorfully festooned reefs of Fiji or Raja Ampat.

They are not as rich with clownfish either. I found some anemone clusters duking it out with the staghorn for a foothold on the substrate, but the plethora of balled-up anemones like those that dot the reef off Kimbe Island in Papua New Guinea eluded us. Borneo is more about lettuce corals and Acropora. The highlights that will percolate through your memory from diving Borneo will likely be the shallow hard coral reefs.

Night divers came back raving about their immersion at the Dark Side. Like all the night dives our trip offered, this was a shallow reef resplendent with macro creatures. Although a mobula ray and a green turtle swam tantalizingly close, the reef minutiae — juvenile bobtail squids, orangutan crabs, free-swimming flatworms, tiger mantis shrimp, and Chromodoris annae nudibranchs — were the popular dinner conversation topics.

Our third morning offered the option of reef diving or interacting with whale sharks. We opted for the whale sharks, especially when the crew told us that we had a 95% probability of encountering them. There is a reason for the high percentage: A floating fishing platform with big nets strung beneath, called a bagan, has tiny bits of fish constantly floating in the water column below. These morsels are perfect for the filter-feeding whale sharks, so a chain of commerce evolved. The bagan attracts the whale sharks, the whale sharks attract the divers, and everyone gets paid a little something — everyone except for the tiny fish that get caught in the nets each night, but that would happen with or without the divers.

The whale sharks weren’t going anywhere while the fishers were scooping ladles of tiny fish from above, so we didn’t have to hurry. There were typically two or three whale sharks hoovering through fish soup below the bagan, totally oblivious to our presence, whether we were on scuba or snorkel. One accommodation we made was to use strobes only at very low power to avoid disturbing the whale sharks. Given the suboptimal water clarity, proximity would yield the best encounters anyway, so minimal strobe output was the best practical and environmental approach.

Traditionally there is an afternoon nondiving option at this point in the itinerary. A brackish lake in the middle of Kakaban Island in the Derawan Archipelago is populated by stingless jellyfish. This location’s popularity has grown steadily over the decades to the point that the sunscreen that tourist hordes slather on has killed many of the jellyfish and diminished the encounter’s significance. We had a better option: turtle hatchlings.

A turtle sanctuary on Sangalaki Island, which lies within the Derawan Marine Protected Area, is famous for its sea turtle conservation efforts and opportunities to interact with hatchling turtles. This area has Southeast Asia’s largest nesting population of green sea turtles, with 20 to 30 nesting each night and more than 7,000 during the year. Boat landings are difficult during the wet season, so the dry season from April to September is the best time for visitor access.

In an extraordinary bit of turtle husbandry, the baby turtles are curated from the eggs that mother turtles lay in the soft sand beach and relocated to the hatchery for safety. After the eggs hatch, the baby turtles are kept in a pool for a maximum of 24 hours to protect them from land predators and ensure they are strong enough before being released. By timing our visit near dusk, we were able to observe the entire process of releasing several hundred turtles into the sea. We were allowed to observe, photograph, and even assist in the process, provided we stayed outside the established lanes along the beach that the turtles would follow according to their instinctual behavior.

The week progressed with a dive profile that rewarded wide-angle enthusiasts with large sea fans, black coral, and whip gorgonians in the 60- to 80-foot (18- to 24-m) range, while macro shooters found longnose hawkfish, schooling fusiliers, and pyramid butterflyfish in the same environments.

We frequently encountered crocodilefish, green turtles, spotted sweetlips, regal angelfish, bigeye trevallies, and even bumphead parrotfish in the shallows. The bumpheads remained more skittish than I’ve seen them in Palau or Sipadan, so my photos won’t prove it, but they were among the usual suspects. Lighthouse North and Small Fish Country wereamong the more productive of these sites. Small Fish Country was so superb that popular demand made it the final dive of the trip.

Several land-based resorts with small jetties are along Derawan Island. Judging from the boat traffic, which was primarily dinghies towing banana boats, I gathered that most tourists were fun-in-the-sun revelers. Just as we saw no other dive boats out at sea, we saw no shore divers in the water. There are land-based dive shops on the island, and a simple online search reveals multiple options.

Despite the availability for divers, we were alone in the water at Darma Point, surrounded by dozens of cornetfish, batfish at cleaning stations, dwarf cuttlefish, twinspot lionfish, and even a bamboo shark, which I regrettably did not see. I found a pair of stonefish snuggled up to one another on the seafloor, and their proximity allowed me to get both of them in the same frame with my 100mm macro lens.

We reached our final day of diving too soon. I had a 6:30 a.m. flight the next day, so I opted to do only the first dive at Fonsi Point. While I could have done the second dive shallower than 30 feet (9 m), I wanted to be abundantly cautious.

I needed some subject discipline for this dive, as I had spent the week celebrating the hard corals and devoted too little time to the creatures that populate the shallow reef. This final dive would be all with my 100mm macro lens so I could capture the long-snout butterflyfish, regal angelfish, and dozens of other species of small Indo-Pacific butterflyfish I couldn’t name without a fish identification book.

The divers who went on the second dive told me about the 20 hawksbill and green sea turtles they saw. I can’t say the turtles’ presence is a direct result of the sanctuary’s conservation efforts, but their work clearly doesn’t hurt.

Now that I know more about Indonesian Borneo, compared with the little I knew before the visit, the only change I would likely make is to book a 10-day trip instead of a seven-day excursion. When it came time to leave, I definitely wasn’t ready to go home.

How to Dive It

Getting there: Tarakan is the gateway to Indonesian Borneo and is accessible directly from Jakarta or via connecting flights from Bali or other Indonesian international hubs. The most practical options we found were from Bali, connecting through Surabaya on Lion Air, although we had a long layover. Going through Jakarta on Batik Air is a more direct route and has a noon departure rather than 6:30 a.m. Another option is from Singapore via Balikpapan.

Conditions: The ideal window for diving is during the dry season, which runs from April to October. You can expect water temperatures in the 80s°F (27°C to 32°C). Semporna and Kota Kinabalu in Malaysia have the nearest chamber facilities, but Jakarta is the closest for divers staying in Indonesia. After a hospital evaluation, medical staff will consider the diver’s condition and determine if evacuation is necessary and where to send the diver. The dive profiles should not be challenging for most divers, but there is always the potential of increasing decompression risk by doing too many deep or repetitive dives, having an underlying condition such as a patent foramen ovale (PFO), or simply being dehydrated. Even though Borneo is remote, DAN can help arrange any necessary medical care.

Currency: If you bring U.S. currency, ensure that you have new, clean, large-denomination bills. Banks or foreign exchange offices might not accept old, torn, or marked bills, and the exchange rate for smaller denominations is not as favorable. Most places accept Visa and Mastercard, but they may not take American Express. It’s a good idea to carry some Indonesian rupiah for excess luggage charges at the airport. You can withdraw the currency from most ATMs using your international debit or credit card.

Visas and customs: Residents of most countries, including the U.S., can obtain a 30-dayvisa on arrival. You can apply online in advance at evisa.imigrasi.go.id or at Indonesian international airports. You will need a passport that is valid for at least six months from your arrival date and a return ticket or a ticket to your next destination. The online customs declaration form is at ecd.beacukai.go.id/cdonline.html. It requires your flight number and date, and you can only complete it a few days before your trip.

Explore More

Find more about Borneo in this bonus video and photo gallery.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025