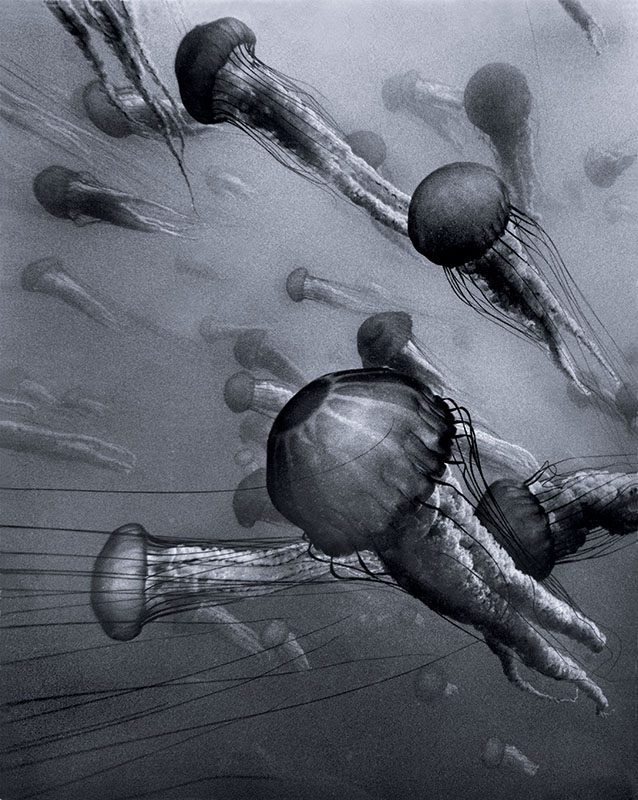

I knew Chuck Davis’ photography long before I met the man, so interviewing him revealed a wealth of fascinating information. One of the most surprising things I learned is that Chuck shot on film all the black-and-white images featured here and processed and printed them in his darkroom.

He is famous as a master of underwater black-and-white photography, but I assumed he shot digital and converted his files to black and white in Lightroom or Photoshop. Digital tools have become standard, even for legacy enthusiasts (like me) who began with fingers yellowed from fixer and the smell of Dektol paper developer lingering in our noses. Davis is an ardent traditionalist, which is different from being a Luddite, as he is quick to point out.

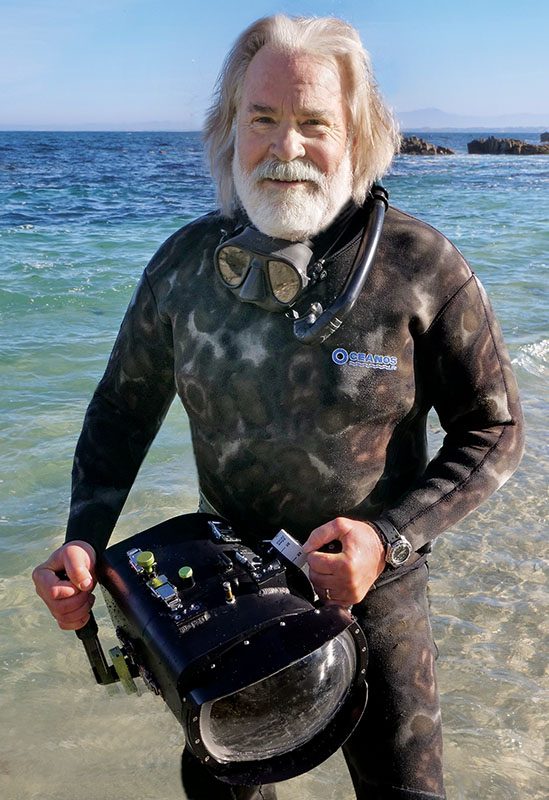

Davis shoots with a medium-format Contax 645 and a Zeiss 35mm wide-angle lens. He devised a custom housing that his contacts in the motion picture industry in California designed and manufactured. Shooting the 645 format allows him 16 exposures on a roll of 120 film and 32 on a roll of 220. Having only 32 exposures per dive requires a different imaging philosophy from the virtually unlimited capacity we have with digital. He sees his photographic opportunities differently and by necessity is more circumspect and disciplined about each click of the shutter.

His film of choice is Kodak T-Max, which he processes according to the range of light from the day of the shoot. He might be shooting in a kelp forest, for example, where the shadow detail is important and usable highlights seem in control. Knowing that he can control the contrast in development, Davis makes sure to give adequate exposure to the deep shadow areas. He may process it differently if he decides to shoot an upward angle with a sunburst dominating the composition.

After processing the negative, he loads the film carrier into his Ilford enlarger, which has a compensating head designed specifically for black and white. His paper of choice is Ilford variable contrast fiber paper; he chooses the contrast grade that will best complement the subject. Sometimes he’ll use exotic techniques such as split printing, in which he renders shadows and highlights separately.

Davis recycles his chemicals to reduce his carbon footprint and no longer uses running water when printing. Instead, he employs a special rinse aid before bathing his prints in his archival washer, significantly reducing wash time and conserving resources. He says of his darkroom, “It is my happy place. As long as they keep making film, I’ll keep using it.”

Born in 1954 in Bangor, Maine, Davis became an island boy at age 5, when his father became principal of Martha’s Vineyard Regional High School in Massachusetts. His mother was a nurse at Martha’s Vineyard Hospital. The island was very rural then, and Davis grew up with the smell of salt air rolling in from the North Atlantic. The ocean was a living thing that he experienced through freediving and spearfishing. He had a paper route that funded occasional purchases of dive gear, such as blue Voit fins to match those Mike Nelson wore in Sea Hunt, although they looked gray in a black-and-white television show.

An interview on Rfotofolio.org documents those early years, including his early photographic inspiration: “[A] year or so after learning to scuba dive … [I] took up underwater photography very seriously. I was motivated by the amazing images I had viewed on TV via Lloyd Bridges’ Sea Hunt and the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau and still photos I had seen in Cousteau’s books such as The Silent World and World Without Sun — and the wonderful images I had seen in a book called Camera Below by Paul Tzimoulis and Hank Frey … and of course the photographs I would see each month in Skin Diver magazine.”

Davis’ first underwater camera was a Nikonos II with a 35mm lens, which he purchased in 1968 for $160. With rolls of Tri-X film and a Sekonic light meter, he shot using available light and learned by trial and error. His high school had a darkroom, and he learned the complexities of the Zone System, developing the skills to manipulate the negative and the print. He went to the Boston Sea Rovers annual shows and absorbed all he could from the underwater photography workshops.

By college age he was using Kodachrome film and a strobe and wanted to go to the Brooks Institute of Photography, the nation’s premier photo education facility. His dad contended that he needed a real job to fall back on, so he attended the University of Massachusetts Amherst and earned a bachelor’s degree in fisheries biology. His fisheries department advisor asked him what he wanted to do now that he had his degree, and his answer was to go to the Brooks Institute and be an underwater photographer.

With his worldly goods loaded into his Volkswagen Super Beetle, Davis headed west. He met Ernie Brooks soon after enrolling. Brooks’ dad had founded the school, and Ernie had already gained acclaim for his underwater black-and-white photography. Their first collaboration was a documentary film spanning a year of going out on Brooks’ boat with cinematographer Louis Prezelin. It was an amazing apprenticeship, and Davis also met Mal Wolfe during that time. Wolfe brought him into the world of IMAX cinematography just as Prezelin had provided the early introduction that led him to his work with the Cousteau Society.

Davis started as a volunteer cameraman with the Cousteaus. Davis was only loading cameras and pulling focus, but he was working with Jacques Cousteau and his son Jean-Michel. While it didn’t last forever, he stayed in touch over the next five years, hoping they would hire him. Meanwhile, he joined the special effects industry in Hollywood, where he learned new skills and banked some money. When the Cousteaus launched their expedition ship Alcyone, they invited Davis to join their 13-person crew. Sometimes he would work on the Calypso as well. Davis still remembers his time with Jacques at the helm as his dream job. For the next 20 years Davis freelanced for the Cousteau Society and Jean-Michel’s Ocean Futures Society.

For all his cinematography work, stills — particularly black and white — remained his personal passion. It is logical that someone immersed in the art of black-and-white photography would be familiar with the images and words of Ansel Adams. Davis paraphrases Adams describing two kinds of photographic work in a documentary: assignments from without and assignments from within. The former are for-hire assignments to pay the bills, and the latter are self-assignments to satisfy your inner desire.

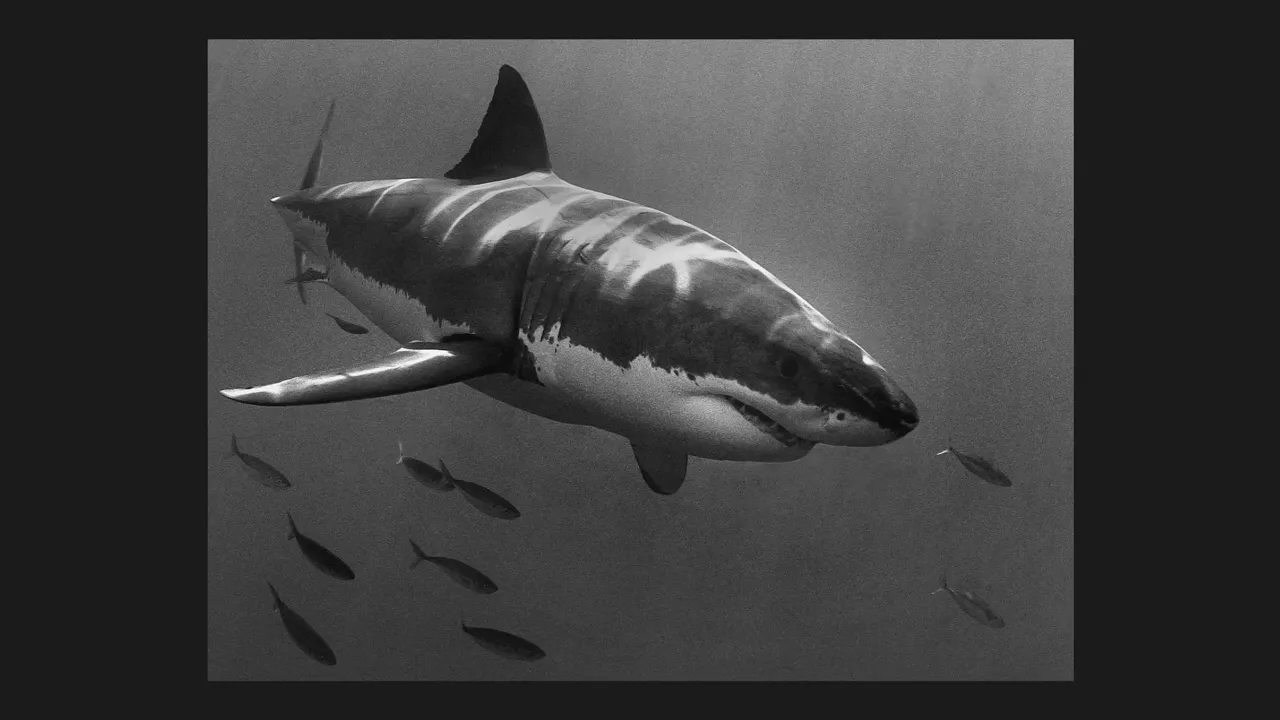

Davis has done plenty of self-assigned work, much of it on California’s central coast. He agrees with scientists who consider the West Coast the “Serengeti of the Eastern Pacific.” The stretch from his backyard — Monterey Bay to Carmel Bay, points south such as Point Lobos, and the northern reaches of Big Sur — provide constant inspiration. He will venture as far south as Baja California and considers this whole stretch of reef and its adjacent pelagic environment as one interconnected, living organism.

Davis spends most of his time on any given dive just looking and absorbing the range of light. He doesn’t swim around a lot but finds nice backdrops and waits for a subject to appear, whether it’s a jellyfish or a harbor seal in the kelp. He’s fortunate to live in an area where traditional darkrooms still abound. There seems to be a renaissance of interest in darkroom techniques, and schools are teaching them again. A jazz music aficionado, Davis will spend hours alone in the darkroom with Miles Davis piping through the speakers and only a GraLab timer to measure the passage of time. It is the antithesis of a frenetic digital workflow, and the discipline, craftsmanship, and vision are evident in every print.

His fine art prints have been in special exhibitions by the Ansel Adams Gallery, the Christopher Bell Collection Gallery, the Center for Photographic Art, and the Brooks Institute. His work is also included in the Mariners’ Museum, and he is the author and photographer of California Reefs published by Chronicle Books. His motion picture credits include filming on several IMAX films, including Ring of Fire (underwater lava scenes), Whales: An Unforgettable Journey, The Greatest Places, Amazing Journeys, and Search for the Great Sharks, and two Academy Award-nominated IMAX films, Alaska: Spirit of the Wild and The Living Sea (underwater/marine scenes of Monterey Bay). You can see Davis’ work at tidalflatsphoto.com.

Explore More

Learn more about Chuck Davis and his work in these videos.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2023