Helping marine biologists push for larger MPAs

“Every scrap of biological diversity is priceless, to be learned and cherished, never to be surrendered without a struggle.”

E.O. Wilson

I first attempted to place an acoustic tracking tag onto a passing shark in December 2016. My buddy and I rolled backward off our skiff into the gray-blue Costa Rican water and descended along the submerged rock wall. Halfway down I spotted a 10-foot tiger shark 50 feet below and dived to intercept it as it patrolled the sandy shelf at the wall’s base.

As I closed to within 5 feet, the shark turned to face me — this was my first close look at its dark, round eye, broad head and saw-shaped teeth. I felt a wave of adrenaline despite knowing that sharks rarely bite people. The shark paused, seemingly pondering whether to fight or flee. I had no idea what it would do when I stuck it with a spear tip. The shark turned, swept its long tail side to side and glided out of range.

The next day I tried again, descending 110 feet to the same sandy shelf, where I stretched two surgical tubing bands to load my speargun. My buddy, Elpis, got my attention as three tiger sharks passed nearby. Kicking hard to catch the last shark in the line, I aimed the speargun from 2 feet away and pulled the trigger. The spear tip pierced the shark’s thick, striped skin just below the dorsal fin. Startled, the apex predator shimmied off with its tracking tag secure. Acoustic receivers planted around Cocos Island’s waters detected this shark for about two weeks before the signal disappeared.

Background

My journey to help scientists began one year earlier when a friend introduced me to marine biologist Randall Arauz, winner of a Goldman Environmental Prize for his work exposing the brutal shark-finning practices in Costa Rica. Arauz had an extra spot on a research expedition to Cocos Island in four weeks and invited me to join him. I had no prior experience in shark science but was comfortable with a speargun, had taught research diving at the University of California, Berkeley, and had logged thousands of dives worldwide. Happy to contribute to conservation efforts, I took the spot.

Arauz and researchers from the MigraMar consortium take volunteer divers on citizen science expeditions to tag and track pelagic sharks as they migrate through the Eastern Pacific. Scientists use the data to advocate for larger marine protected areas (MPAs) to protect sharks from overfishing. Volunteers pay typical liveaboard prices to help researchers defray the high cost of these expeditions, and in return they get to see shark science and conservation up close.

For years longline fishers have cast miles-long fishing lines with baited hooks near Cocos and the Galápagos. They haul aboard live sharks, slice off their fins and kick the finless animals back into the ocean to drown or be eaten. Shark finning is illegal in many countries but challenging to prevent.

Killing sharks causes a domino effect that decimates other species since apex predators are critical in balancing local food webs. When sharks disappeared off North Carolina in the early 2000s, local populations of rays dramatically increased, devouring shellfish and destroying the local shellfish industry. It is a global problem, as exemplified by the recent discovery of a large fleet of Chinese fishing vessels at the edge of the Galapágos Islands catching squid, sharks, tuna and billfish. The International Union for Conservation of Nature classifies numerous shark species, including tiger and scalloped hammerhead, as near threatened, endangered or critically endangered. Many shark populations are rapidly heading toward extinction, so better protection is crucial for their survival.

Cocos Island

Inspired by what I saw on my first two trips to Cocos, I returned to the Pacific islands of Cocos, the Galápagos and Mexico’s Revillagigedo Archipelago seven times over four years. On my latest trip to Cocos Island, just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, biologists and volunteers boarded the Argo for a 36-hour ride to the volcanic island shrouded in a lush tropical forest. In darkness each morning, we boarded a skiff with biologists Lisa Hoopes and Kady Lyons of the Georgia Aquarium and Alex Hearn of Universidad San Francisco de Quito in Ecuador to pull sharks boat-side to take blood and tissue samples and attach tracking tags. The samples will determine if pelagic sharks have absorbed large amounts of microplastics.

Just after sunrise, with the boat-side work complete, we returned to the Argo for breakfast and full days of diving on nitrox to tag sharks underwater. We dived at Manuelita, an islet where Galápagos, tiger and scalloped hammerhead sharks regularly patrol. Hammerheads glide into cleaning stations filled with barberfish, while divers hide behind rocks, wait for the sharks to approach and then lunge forward to tag the shy creatures.

Revillagigedo

On another citizen science trip just before the pandemic, I traveled with cinematographer Mikael Gustafson of Sea Stand Productions to the Revillagigedo Archipelago to film Mauricio Hoyos tagging and tracking sharks. We boarded Quino el Guardian in Cabo San Lucas, loading dive and camera gear for the 24-hour ride to our first stop, San Benedicto Island. Hoyos inspired the Quino’s owner, Dora Sandoval, to run these trips, enabling divers to learn about shark science and contribute to research efforts. He teaches volunteers from around the world about local sharks and rays and encourages them to spread the word about looming extinctions caused by shark finning.

At night, Hoyos brought sharks onto the rear deck, where volunteers installed hoses in the sharks’ mouths to circulate seawater across their gills. They covered the sharks’ eyes with rags to calm them and then measured the sharks before Hoyos surgically installed acoustic tracking tags in the animals’ bellies and released them. We spent a week rising at daybreak to film Hoyos tagging sharks and taking tissue samples from passing mantas at three of the four Revillagigedos islands.

We also filmed playful bottlenose dolphins and giant oceanic manta rays along with silvertip, silky, whitetip, scalloped hammerhead, tiger, Galápagos and whale sharks. The abundance of creatures inspires divers and researchers to visit, supporting scientific discovery and a tourist economy that sustains rather than kills marine life. As a photographer, I enjoyed taking photo IDs of the distinct patterns on mantas’ bellies to help biologists estimate local population sizes. We watched these intelligent giants glide overhead and arch their 20-foot wingspans to feel our rising bubbles tickle their bellies.

“On a trip like this, you can have up-close and personal encounters with manta rays and sharks,” said Madeline Wewer, a marine geologist and divemaster. “It’s becoming more and more important to know about our oceans and the marine life in them and to understand more about humans’ impact on them and the environment.”

“When people come to these places and see these animals face-to-face, they change completely,” said Hoyos, who also leads trips to see great white sharks at Mexico’s Guadalupe Island. “Instead of being afraid of sharks, they want to protect them.”

Success in Mexico

In a significant win for ocean conservation, research by Hoyos and colleagues helped influence the Mexican government to establish an MPA of almost 58,000 square miles (150,000 square kilometers) around Revillagigedo in 2017. The Revillagigedo Archipelago National Park is the largest MPA in continental North America. The study, which was backed by work from citizen scientists, proved that silvertip sharks traverse the islands to mate, feed and hunt at one tiny island pinnacle (Roca Partida) and birth their pups at others (San Benedicto and Socorro, 70 miles away). Protection of the waters around the four islands has stopped fishers from killing sharks before they have a chance to mate or birth their pups.

Ongoing Battle in Costa Rica and Ecuador

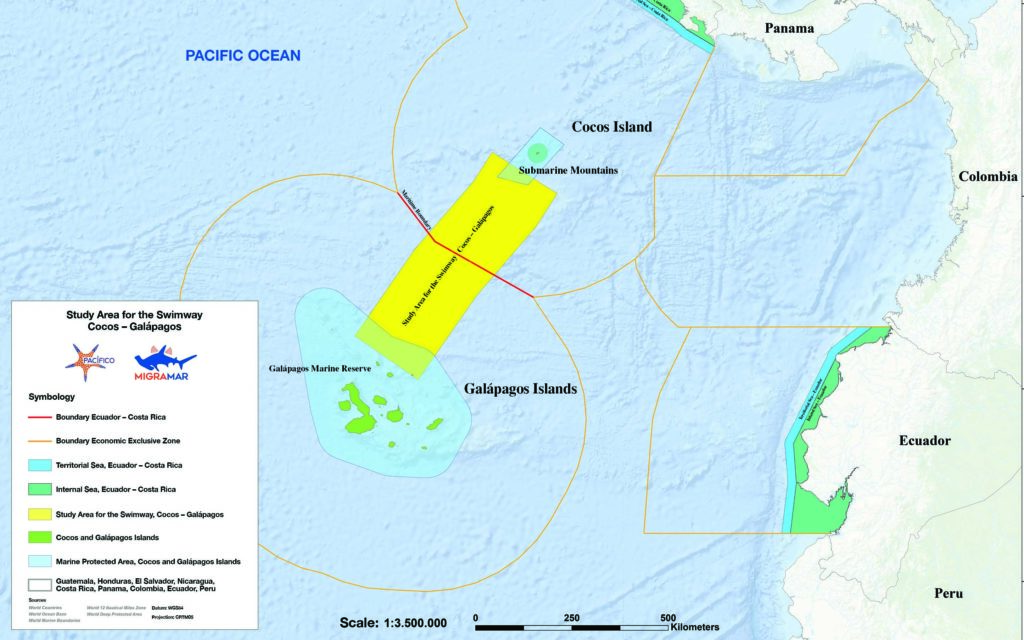

In Costa Rica and Ecuador, the battle to expand MPAs continues. Energized by the recent naming of the Cocos–Galápagos Swimway as a Hope Spot by Sylvia Earle’s Mission Blue, MigraMar biologists are fighting to get Costa Rica and Ecuador to establish a 400-mile-long protected swimway connecting the two smaller MPAs around Cocos Island and the Galápagos Islands.

Biologists face ongoing challenges in funding expensive fieldwork and influencing politicians. Recruiting citizen scientists helps solve the funding problem and helps influence public opinion when divers tell their stories.

“We need to feed information to the public so we can create a massive movement,” Arauz said. “It starts as a trickle, but then we can turn it into a cascade, a tidal wave. And to do this, we need everybody to be involved.”

A United Nations report projects that 1 million species will go extinct in the coming decades. Citizen science can help raise public awareness to advocate for the creation and enforcement of larger safe havens for wildlife on land and at sea.

All research was conducted under permit with governments of the respective countries.

Explore More

Watch a video of a citizen science trip aboard the Quino el Guardian.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021