IT HAD BEEN A BUSY WEEK for the fish surveyors aboard the Avalon ll, and things were just beginning to wind down. The Reef Environmental Education Foundation (REEF) team of 16 volunteer research divers had recorded population estimates for 246 fish species on 26 reef, seagrass, mangrove, and ironshore sites within the benevolent boundaries of Cuba’s Parque Nacional Jardines de la Reina.

The Jardines de la Reina (Gardens of the Queen) archipelago, the park’s namesake, was first declared off-limits to commercial fishing by fiat of Fidel Castro in the 1970s and was later granted no-take marine reserve status in 1996 before becoming a national park in 2010. Besides safeguarding the fish-rich waters of the archipelago, the park also protects 840 square miles (2,176 square kilometers) of prime inshore habitat stretching along 93 miles (150 kilometers) of the country’s southeastern coastline. Cuba’s multidecade efforts have fashioned one of the largest and oldest no-take coral reef marine reserves in the Western Hemisphere. What a joy to explore a fish haven spared the horror of hooks, spears, traps, longliners, and trawlers — a place where fish have a chance to mature into large, prolific breeders. It is just the sort of sanctuary the ocean needs more of.

The story began in 2000, when a few specimens turned up at a tropical-fish-collecting station near Trinidad, Cuba …

Even though we were aware of the park’s abundance and diversity, the moment Anna and I were offered the opportunity to join the Cuba Field Survey, the image of a single little golden fish popped to mind. And oh my, what an interesting bit of fishdom the golden fairy basslet is, considered by fish fanciers far and wide to be the most exciting scientifically described fish from the Caribbean in decades. Most important to us, it is found exclusively on the towering fortress of coral pinnacles skirting the southern coast of Cuba. Without a second thought, we signed on the dotted line.

Months later, we backrolled into the warm waters of the Gardens of the Queen, made a beeline for a series of overhangs paralleling a sandy 65-foot-deep (20-meter) seafloor, and began peering beneath ledges one after another. We didn’t find any golden fairy basslets, but fairy basslets (Gramma loreto, also known as royal gramma), their similar-appearing and closely related sister species, flitted beneath the overhangs in greater numbers than we had ever seen.

Fairy basslet (Gramma loreto)

Hybrid fairy basslet (Gramma sp.)

… the taxonomists’ 2010 descriptive paper pronounced the basslet a new species: Gramma dejongi.

We shared what we knew about the new basslet with shipmates that evening. The story began in 2000, when a few specimens turned up at a tropical-fish-collecting station near Trinidad, Cuba, just west of where our boat was moored. When the shipment arrived in Europe, Ari Dejong, proprietor of a major aquarium wholesaler, immediately realized he had a prize — a beautifully detailed basslet he had never seen or heard of that happened to bear an uncanny resemblance to the royal gramma, a mainstay of the aquarium trade. Sometime later, Dejong shipped three specimens to a pair of prominent fish taxonomists. Even though the new basslet had genetic and morphological markers corresponding to the royal gramma, the taxonomists’ 2010 descriptive paper pronounced the basslet a new species: Gramma dejongi. Could the new fish be an example of recent speciation, as the paper proposed, or a local color variant, as the authors also mentioned? Any way you look at it, the golden fairy basslet is a nifty little fish that pushes the limits of our understanding of evolution.

Sharing a boat with accomplished fish finders certainly made our hunt for basslets easier. They had pointed out three of the golden-scaled beauties by the end of the following day’s dives. I must have kneeled next to a shallow undercut for more than 20 minutes while watching my first dream fish of the trip fin-dance around, often upside down, not an arm’s length away. Like the dozen other golden fairy basslets we observed, it was the lone representative of its species living among robust fairy basslet aggregations below 50 feet (15 meters). Things became even more intriguing when the surveyors began reporting randomly patterned hybrids, offspring of the two sister species.

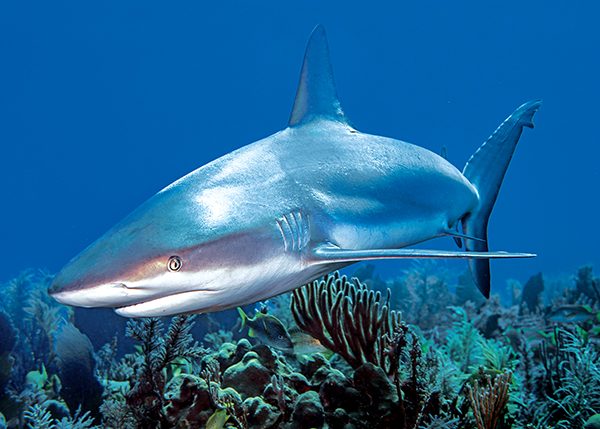

Reef shark (Carcharhinus perezii)

After scrutinizing basslets to our hearts’ content, we began concentrating on the discoveries the surveyors constantly chattered about at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Big fish are an acknowledged staple of the park, and the surveyors had seen a lot. We got a kick out of studying each reef’s squadron of reef sharks — big, sleek, forever graceful, and a joy to be close to as they escorted us around, politely checking out each of us in hopes of handouts. On top of the reef, black groupers roamed freely, and Nassau groupers always seemed to be nosing around. Jacks reigned above as schools of grunts cloaked the reef flats with color below. Goliath groupers and nurse sharks occasionally stole the show. Among all this rich tapestry lived the more than 200 fish species — some large, some small — that the surveyors recorded, including the golden basslet, a terrific addition to everyone’s life list. AD

© Alert Diver — Q3 2022