Keeping America’s Promise

Hometown: Seattle, Washington

Age: 50

Years Diving: 24

Why I’m a DAN Member: Having DAN membership comforts me and my family. Knowing I am taken care of in far-off places gives me one less thing to worry about.

Derek Abbey served for 23 years in the U.S. Marine Corps. As a Weapons Systems Officer, he holds more combat hours in the F/A-18 Hornet than hours in peaceful skies. He left flight operations to become an original member of the Marine Corps Special Operations Command. During his time in the Marine Raiders, he served as a Forward Air Controller, Special Operations JTAC, and Executive Officer.

In 2004, between back-to-back combat deployments to the Middle East, Abbey became a team member with Project Recover, a collaborative effort to use current science and technology to find and repatriate Americans missing in action since World War II. On his first mission with Project Recover, he helped locate an aircraft whose pilot had been in his same fighter squadron nearly 60 years earlier.

After retiring from the Marines, Abbey began a successful career assisting military-connected students with attaining their higher education goals. He earned a PhD in leadership studies at the University of San Diego and currently serves as Project Recover’s president and CEO.

How did you become interested in diving?

I started diving while I was in flight school in Pensacola, Florida. One day I thought, “I’m right by the water. I’ll go try it out.” I got certified and found that flying and diving share a lot of similarities. I approach a dive the same way I would a flight: attending the briefing, reviewing the checklist, executing the dive, and assessing it afterward for what worked, what went wrong, and how to improve on any concerns or safety issues.

Like flying an aircraft, you can get task overload when you are new to diving. You get inundated with information and have to learn how to focus on what is most important in the moment. When I was introduced to Project Recover years later, the organization provided me with a valuable use for diving. It is a strong tool that advances our mission, and I’ve now done more mission-based dives than recreational ones.

Tell us more about Project Recover.

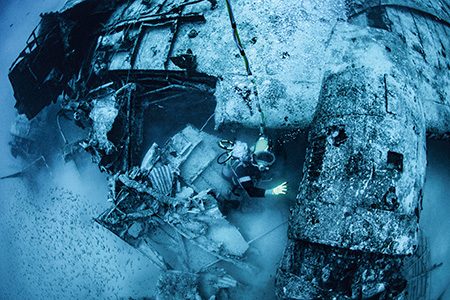

The goal of Project Recover is to provide recognition and closure for families and the nation. It started as individuals taking it upon themselves to find fallen service members, funding the operations to research and find these missing veterans out of their own pockets. The diving started on scuba using rudimentary techniques and following search patterns on the ocean floor.

We’d traverse through the jungle with machetes and eyeballs, forming search lines to look for evidence of aircraft. Reading field reports in the national archives helped us determine where to look. After all the searching, locating, and documenting, we would send our information to the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) and then wait. The DOD created the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency in 2015, which had the capacity for public–private partnerships that allowed us to become an official partner.

We still do the research, searching, and documentation, but we’ve added aquatic and terrestrial recovery. The only thing we don’t do is the official identification of the remains, which is the responsibility of the U.S. government.

What are some important considerations of mission planning?

We are looking for people, not aircraft or shipwrecks. The most challenging work begins once we discover or confirm a site. Science drives our work, and safety is foundational to each recovery mission.

We make sure that all divers are proficient with their fundamental skills so they can be safe with advanced activities such as operating tools or executing recovery techniques. We constantly seek improvements to our contingency and emergency action planning. Skilled divers from the U.S. Navy and dive medical officers from around the world have helped us develop sound protocols to safely execute our dive operations.

Each year we do multiple missions all over the world, performing the vast majority of work overseas and in coordination with the host nation. Americans were not the only people lost and killed in these environments. We might locate former allies, former enemies, or locals, and we are always mindful of encountering these remains. Any time we find a site like that, we document it, turn it over to the host nation, and then communicate it through the State Department so the host nation can take any action they desire.

What is the biggest challenge of these missions?

There is no shortage of missing Americans. We have a database with hundreds of cases and thousands of missing Americans. We assess the database each year to determine which missions we will execute on land and water, based on available time and resources. The biggest challenge is securing the resources we need, particularly financial support.

We’ve significantly scaled up our operation and expanded our technology, including the use of underwater vehicles, drones, and side-scan sonar to help our divers through working with our partners at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, University of Delaware, and Legion Undersea Services.

Most people are not familiar with what we do and don’t realize that 80,000 veterans are still missing from previous conflicts. That translates to millions of people impacted by the loss of family members. People across the country are waiting for answers about what happened and for the remains of their loved ones to be returned.

If someone has been missing for 80 years, does it still affect the surviving family? The answer is indisputably yes. The void associated with loss not only is held by the ones who knew them but also is passed from generation to generation.

The grieving process and opportunity to heal is interrupted, restarted, and continues to be passed on. Those who gave the ultimate sacrifice in defense of our nation are not forgotten. Project Recover is about keeping America’s promise to bring them home, and there is no expiration on that promise.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2024