The deep ocean and outer space: Comparisons of these two realms verge on cliché but are undeniably apt. Both environments are vast and largely unexplored, and both require special technology and skills for humans to visit — even remotely. But unlike space, where the prospect of life remains a tantalizing conjecture, the oceans teem with creatures as alien in appearance as any that we might imagine exist beyond the confines of our blue planet.

Most of the sea’s creatures live in the shallowest 660 feet — the epipelagic or euphotic zone — where penetration of light is sufficient to support a food web based on photosynthetic algae. By some estimates, 90 percent of all marine life lives in this region, feasting (directly or indirectly) on the bounty harvested from the sun.

Below that threshold, light effectively vanishes — the first of many game-changing transitions. As ocean habitat deepens, it becomes more extreme. Pressure increases rapidly, while temperature plummets. As for the availability of food, meals can be few and far between in the dark, snagged on the fly during a chance encounter or scavenged from fallen remains of the abundance above.

It’s not an environment that fosters colors, shapes or habits like those of the marine animals we know well. In deep-water species, hues tend toward the muted, mouths to the toothy and shapes to the long and serpentine. Many of the deep’s inhabitants carry onboard lighting in the form of bioluminescent patches or spots called photophores that help them hide from predators or find meals or mates. In short, plenty of the characters we meet as we plunge into the mesopelagic (660 to 3,300 feet) and bathypelagic (3,300 to 13,124 feet) layers are creepy and cool — in a word, scarismatic.

Evolutionary Relics

The spotted ratfish (Hydrolagus colliei) belongs to the chimaeridae family, a mysterious group that arrived on scene when dinosaurs were a saurian twinkle in some early tetrapod’s eye. Like their more evolved relatives the sharks, members of family chimaeridae have cartilaginous skeletons, claspers (appendages that help the male hold the female during mating) and leathery egg cases. While most of these living fossils shun the shallows, in the icy, green waters of the Pacific Northwest spotted ratfish appear within recreational diving limits, which qualifies them as dual-depth residents. With fetching emerald eyes, ratfish are arguably cute, but they do boast a few quirks, including a venomous spine near the dorsal fin, traces of a third pair of appendages and an oversized, oily liver that helps the fish stay neutrally buoyant anywhere in the water column.

Alternative Lifestyles

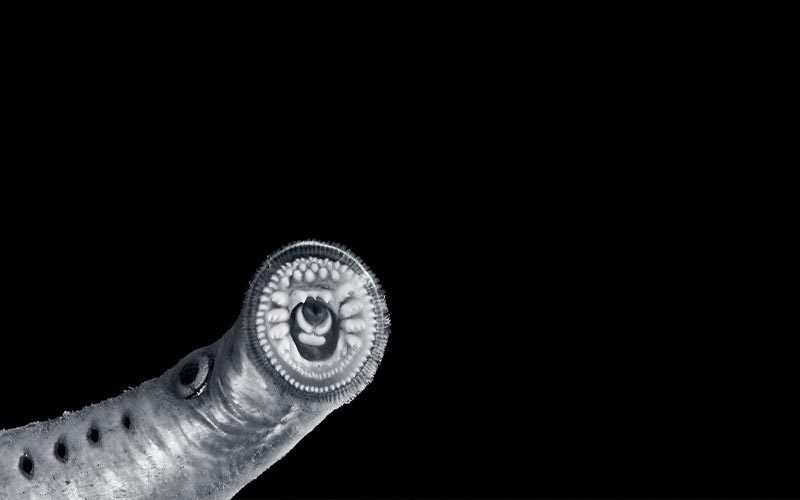

Another odd limb on the tree of life is the sea lamprey. Like salmon, these homely eels begin life in freshwater streams, migrate to the ocean as adults and then leave salt water to head upriver, where they spawn and die — an unusual lifestyle known as anadromy. Here, however, the resemblance ends. The lamprey is a member of an ancient lineage of jawless fish many times removed from its lifestyle doppelganger. That distance is visible in the lamprey’s lack of fins or bones and its distinctive downturned, jawless mouth, which is perfect for clinging and sucking. In oceanic adulthood, the lamprey parasitizes a large passerby, fastening its circular, tooth-lined mouth to the unlucky host, which it doses with an anticoagulant before slurping a meal of blood and tissue. Come spawning time, that same funnel-shaped orifice will affix to a series of river rocks as the lamprey battles its way upstream.

Scarisma: Dragons, Vipers, Daggers and More

While the lamprey exemplifies how weird even the visitors to the deep can be, many full-time residents are truly fearsome to behold. The Pacific blackdragon (Idiacanthus antrostomus), which lives in depths from about 330 to 3,300 feet, is one of the most bioluminescent fish in the ocean, replete with glowing photophores. These light organs run along its back and belly, shine under the eyes and dangle alluringly at the end of a long chin barbel, which the females use to attract prey. Males and females differ to a frightening degree. The 3-inch he-dragon seems a sad echo of the formidable female. Living only long enough to mate, males lack chin barbels, teeth and even stomachs — features the 2-foot she-dragons have aplenty.

Voracious predators, the females have enormous sharp teeth and multiple distensible stomachs that allow them to snag and gulp huge meals — handy traits where food is rare and stockpiling necessary. Big gulps get an assist from yet another exotic adaptation: a head that can bend completely backward to allow the mouth to open unusually wide. An odd bit of developmental biology makes this feat possible. Called the occipito-vertebral gap, it’s a bit of flexible notochord left over after the rest of the structure has ossified (turned to bone) from tail to head. In other fishes, backbones harden from the head downward.

A dragonfish relative, the viperfish (Chauliodus sloani) is a member of the same family (Stomiidae) and a sometime snack of its cousins. But for sheer wickedness of appearance, most bets are on the viperfish, with its outsized overbite and lower fangs that protrude from the mouth and curve back toward the eyes. Where the dragonfish backbone sports a gap, the first vertebra behind the viperfish’s head serves as a bumper to absorb the high-speed impacts of collisions with the prey it chases down. Like the dragonfish, Chauliodus also fishes with bioluminescent bait, but the viperfish lure glows at the tip of an elongated dorsal fin, drawing an unwary victim directly into the path of the transparent but deadly fangs.

Bioluminescence is handy in other ways, too. Several photophores run along each of a viperfish’s sides to help it hide from hungry mouths that lurk below. This common form of camouflage is known as counterillumination and works by disrupting whatever silhouette — no matter how faint — a creature might cast in the weak rain of photons filtering down from above. Counterillumination also helps hatchetfish (Sternoptyx diaphana) live another day (or night) as they make their way up and down the water column, traveling at night into the more productive upper layers to feed. This behavior, known as vertical migration, is common among deep-water fishes.

The fangtooth (Anoplogaster cornuta) vertically migrates as well. Found in most of the world’s oceans, often at spectacular depths of 16,000 feet or more, this oddball forsakes bioluminescence. Tiny eyes sit atop a head that is freakishly large, accounting for nearly a third of the animal’s 6-inch-long body. Muscular compared to most other deep-water predators (whose bodies were designed for lurking), the fangtooth is thought to be an aggressive pack-hunter with keen chemical and electrical receptors that “smell” and feel the vibrations of anything edible close by. While short on vision, the fangtooth bite packs a wallop. Anoplogaster sports the largest teeth — relative to body size — of any fish in the ocean. The teeth in the upper jaw are large enough to prevent the fish from completely closing its mouth, while the lower fangs, when not in action, are holstered in special sockets inside the roof of the mouth extending upward on either side of — and protecting — the brain.

More Beautiful Than Beastly

Not all of the fauna that flourish in the deep ocean are fierce in appearance; some are actually ethereally beautiful. Snipe eels (Avocettina bowersii) are long, thin stunners whose slender jaws taper and curve outward like the beak of an avocet, a shorebird also known as a snipe. Feeding mainly on small shrimplike crustaceans, adult snipe eels contrast dramatically with their larval young. The thin, leaf-shaped juveniles are transparent and spend their youth in shallow water. With a global distribution, both young and old snipe eels are snacked upon by a host of large ocean predators.

Strangely Familiar

In the dark depths, appearances can be deceptive. One creature that sports some truly alien biology looks surprisingly familiar. Galatheid crabs (which are actually lobsters) are scavengers — dumpster divers of the deep. Sometimes called “pinch bugs” or “squat lobsters,” galatheids favor diets that are unconventional even for gleaners. They dine on fallen trees, coconuts and other woody plant debris that falls to the ocean floor, creating small oases of food. One pale member of this group of crustaceans shared headlines with strange giant tubeworms when hydrothermal vents were first found a few decades ago. Ghostly white galatheids swarm in abundance around the vents, feeding on dead animals and chemosynthetic bacteria.

At the base of this food chain, our story comes full circle in a community of life that is dense, diverse and dynamic — in that respect not unlike the shallow world we visit while scuba diving. Like the experiences and excursions of a dedicated diver, there is much more to the story. The deep sea is a world ripe for exploration, and we are fortunate to live in a time when technology allows us to glimpse it.

Skimming the Surface

The whole story of these ambassadors from below could never be told in the space of a few pages. Several research organizations, including the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute and Moss Landing Marine Lab, collaborated with photographer Jason Bradley to make these images possible.

© Alert Diver — Q3 Summer 2013