Q: When administering first aid oxygen to an injured diver, is there a risk of oxygen toxicity? I’ve heard about “air breaks” — are those necessary when providing first aid oxygen?

A: There are two forms of oxygen toxicity, and they are identified by the area of the body most affected: the central nervous system (CNS toxicity) and the lungs (pulmonary toxicity). Each results from a particular type of exposure to oxygen.

CNS toxicity occurs only in hyperbaric environments (those in which the pressure exceeds sea-level pressure) and can manifest as seizures. The risk of seizure due to CNS toxicity accounts for the generally accepted oxygen partial pressure limit in recreational diving of 1.4 ATA. CNS toxicity risk increases as the partial pressure of oxygen increases.

Within hyperbaric chambers, the maximum oxygen partial pressure allowed is 3 ATA. Most treatment protocols are performed at 2-2.8 ATA of oxygen. Exposure to these levels is appropriate in controlled clinical settings and is not harmful. In the event of acute oxygen toxicity, the controlled, dry environment is not associated with the risks divers face, like drowning. To further reduce the risk of oxygen seizure during hyperbaric treatment, some facilities also provide air breaks, which are thought to reduce oxygen seizure risk. Despite the high oxygen partial pressures experienced in hyperbaric chambers, seizures are very rare.

Pulmonary toxicity, on the other hand, results primarily from prolonged exposures, not just elevated oxygen partial pressures. However, the onset of pulmonary toxicity is accelerated in hyperbaric environments.

Pulmonary oxygen toxicity describes the irritation of lung tissue resulting from excess free radical production. The prolonged use of high concentrations of oxygen can overwhelm our cellular defenses. Symptoms may include substernal (behind the sternum) irritation, coughing, a burning sensation with inspiration and reduced pulmonary function. When breathing 100 percent oxygen at sea level, symptoms may occur after 12-16 hours of exposure. As such, pulmonary toxicity is generally not a concern in open-circuit recreational diving and other prehospital settings, and it does not require special prevention strategies or the use of air breaks.

From time to time, we hear about divers administering oxygen first aid and confusing it with chamber treatment protocols by giving air breaks to the injured diver. Air breaks are unnecessary and inappropriate for a diver breathing 100 percent oxygen at near-surface pressure. Giving air breaks while administering oxygen first aid diminishes the oxygen pressure gradient and reduces the oxygen window by introducing nitrogen into the diver’s breathing gas. This slows the elimination of nitrogen from the diver’s body.

If you participate in prolonged evacuations from a remote location, allowing occasional air breaks is acceptable, although these would happen naturally as the diver eats, drinks and goes to the bathroom. It isn’t necessary to plan these air breaks at regular intervals.

— Nicholas Bird, M.D., DAN CEO and chief medical officer, and Eric Douglas

Q: I’ve been diving for 20 years, and my ears are getting worse for the wear. I hear many people singing the praises of vented earplugs. What is DAN’s opinion of them?

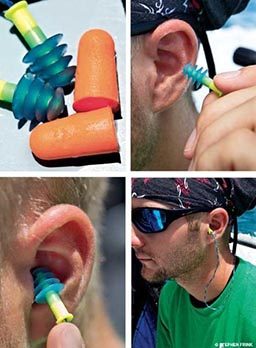

A: In the past 10 years no new information has surfaced to warrant any change in DAN’s recommendations regarding the use of vented earplugs. Although traditional, nonvented earplugs are never appropriate for diving, some divers report improved equalization while using vented earplugs. Others, however, report no improvement. Manufacturers of these products claim they make equalization easier, but since pressures must still be equalized we do not know why that would be the case. Although the ear canals may remain drier, this does not change the fact that the pressure in the middle ears must still equalize to the surrounding water pressure. Originally, vented earplugs were designed to reduce the occurrence of otitis externa (swimmer’s ear). For this purpose the earplugs have demonstrated some value. We know of no consistent evidence, scientific or anecdotal, to confirm significant improvement of equalization.

Longtime DAN consulting physician and ear, nose and throat surgeon, Dr. Cameron Gillespie, recently confirmed that users are not likely to be injured by using vented earplugs while diving. However, Gillespie does have some reservations about their use on the surface. Earplugs inhibit normal hearing and may hinder buddy communication and awareness of crew instructions. If earplugs are worn with the hope of easing the process of equalization, they should not be used in an attempt to compensate for sinus congestion or other major obstacles to equalization, as these obstacles preclude diving. In addition, since the risk of leaking cannot be eliminated completely, diving with a perforated eardrum or pressure-equalization tubes is not recommended at any time — with or without earplugs.

— John U. Lee, MSDT, EMT, CHT, DMT, DAN medical information specialist

Q: I’ve just finished a week of heavy diving, and many in our group have scheduled massages for the afternoon of our last day at the resort. Is it possible a deep-tissue massage could lead to an increased risk of decompression sickness?

A: Massage has not been clearly associated with any cases of decompression sickness (DCS) in which DAN has been involved, and we are not aware of any study done to address this question. The simplest piece of advice is that postdive deep-tissue massage should probably be avoided so the risk of diagnostic confusion is minimized. Deep-tissue massage, like exercise, has the potential to cause soreness in tissues and joints that may be similar to symptoms of DCS. Such diagnostic uncertainty can cause significant anxiety, lead to unnecessary hyperbaric chamber treatment and, most dangerously, result in divers ignoring actual symptoms of DCS, believing them to have resulted from the massage.

A more speculative and purely theoretical concern is the risk of bubble micronuclei development. The nature and action of micronuclei have not been confirmed, but it is believed they are the seeds from which bubbles form. Tissue stimulation could increase blood flow, which may either enhance elimination of gas from tissues or precipitate problematic bubble formation. There is no clear sense of what massage might do, and this effect would likely vary depending on dive profiles and intensity of the massage. Conservative depth/time profiles are the most reliable way to mitigate DCS risk.

— John U. Lee

Q: I am an instructor with a student experiencing some equalization difficulty. He is in his mid 20s and had tubes in his ears as a child. Though he has completed most sessions and dives without a problem, once while in the pool and once after an ocean dive he came to the surface and reported feeling dizzy. Both times I had him rest for a few minutes, and he seemed fine after that. Do you have any ideas about what might be causing this?

A: What you are describing is not at all uncommon. Some people are very sensitive to changes in barometric pressure, and these changes can trigger dizziness. Although the cause of your student’s symptoms is difficult to determine without additional information, it may be related to asymmetrical stimulation of his inner ears.

Whenever we equalize our ears, the middle ear receives small amounts of air through the Eustachian tubes to compensate for the barometric pressure on the outside of the eardrum. The middle-ear space lies adjacent to the inner ear, and changes in middle-ear pressure may influence adjacent inner-ear structures. The inner ear serves not only as an auditory organ, but also provides our brains with information about body position, movement and acceleration. When inner-ear stimuli are asymmetrical between the right and left ears, this can cause dizziness or even vertigo (sensation of spinning). When these symptoms result from a pressure differential between the ears, this is known as alternobaric vertigo.

A medical history of ear tubes is not necessarily a problem for divers, but it is possible your student may need additional time to equalize and may be at a higher risk for ear barotrauma (although his dizziness is not related to this risk).

Advise your student to consult an ear, nose and throat physician (ENT). It is not necessary to seek out a physician trained in dive medicine, as any ENT should be perfectly able to understand the stresses divers undergo. A consultation with an ENT may provide options that make equalization easier and may help prevent injuries. Should the ENT have any dive-specific concerns, encourage him or her to contact DAN.

— Matias Nochetto, M.D., DAN director of operations and outreach, and John U. Lee

© Alert Diver — Q4 Fall 2011