My wife, Teresa, and I left for Tahiti on June 5, 2018, for 11 days of sailing through French Polynesia. This trip was an extended version of a seven-day trip that we had thoroughly enjoyed several years before. While in the marina, we looked forward to taking advantage of the dive excursions from inflatables off the ship’s stern. On June 9, we prepared for our first two-tank dive in Bora Bora.

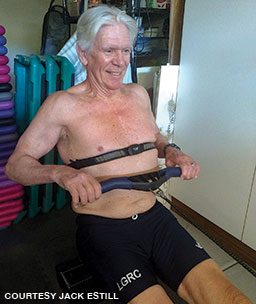

I was 71 years old at the time, and Teresa was 62. We exercise regularly, are in good health with no medical conditions and take no medications. I am a competitive rower, and Teresa teaches exercise classes. We are experienced recreational divers with hundreds of dives worldwide during the past 30 years. For these dives we were using nitrox and our own computers. Since we had not been diving for almost a year, we refamiliarized ourselves at modest depths — 80 feet on the first dive and 60 feet on the second — with three- to five-minute rest stops at 15 feet, ensuring our tanks had at least 500 psi in reserve. Both of us felt good during the dives and had no trouble with buoyancy, fatigue or situational awareness.

After an appropriate surface interval and some rehydration, we jumped back in at another beautiful dive site, followed the same routine and felt fine after the dive. About a minute after returning to the ship, however, I coughed up a tablespoon of foamy, red blood. I felt normal with no other symptoms, so I went to my cabin and took a quick shower, during which I coughed up more foamy blood, this time orange rather than red. Recalling an article about immersion pulmonary edema I had recently read in Alert Diver, I realized this symptom was unusual and potentially dangerous. After talking with Teresa about it, I decided to call DAN.

The DAN medical professional who answered the 24-hour emergency hotline suggested that I go to a hospital for an X-ray and thorough checkup. With the only open hospital a helicopter ride away, I let DAN know I would first consult with the ship’s doctor. After learning about my symptoms and alerting the captain that I might need an emergency evacuation, the doctor took my history and performed a complete evaluation.

My lungs sounded clear, and there did not seem to be any immediate emergency, so the doctor told me to relax for the rest of the day and check in the next morning. I updated the DAN medics, who preferred that I get an X-ray and physical, but they understood the situation and told me they were available for further assistance, particularly if my condition worsened. While I had no further problems, and my morning checkup was clear, the ship’s doctor ruled out any further diving and advised me to see my regular physician when we returned home.

After finishing the trip, I called my doctor and explained what had happened. He was puzzled and wanted to see me right away. After listening to my heart, he put his stethoscope to my ears. Instead of hearing bump bump, I heard bump swish. He referred me to a cardiologist, who performed a battery of tests, including an echocardiogram, and diagnosed me with exercise-induced mitral valve prolapse, an uncommon but known injury.

The damage likely occurred a week before the Tahiti trip, when I was in a competitive eight-man shell for an early morning row after sleeping poorly due to some business stress. Instead of a nice recreational row, the crew wanted to do a practice race. I did not pay enough attention to how I felt and overstressed my heart, tearing two of the chordae that control the mitral valve, causing the valve to leak. I felt uncomfortable after the row but did not engage in any additional vigorous exercise before the dive trip. The mitral valve damage caused some blood to recirculate to my lungs with each heart compression; with the added pressure from diving, some blood leaked through the lung blood vessel walls and into my alveoli.

Under the circumstances, I was glad we had planned easy dive profiles for our first outing. Fortunately, I had read about pulmonary edema, which spurred me to ask questions and stop diving in a situation where additional dives could have had much worse outcomes. Open-heart surgery can completely repair this type of mitral valve injury with no limitations or medication after proper rehabilitation. The surgery was daunting, but I was motivated to recover; in consultation with my cardiologist, I returned to easy rowing within six weeks and competitive rowing as well as diving within a year.

I learned several lessons from my experience. First, divers should continue to educate themselves. There is no substitute for more knowledge, and DAN is an excellent source for up-to-date information about dive-related risks, opportunities and research.

Second, I will never go without DAN membership. Around-the-clock access to professionals with knowledge of dive medicine if an emergency occurs anywhere in the world can be tremendously reassuring and potentially lifesaving. DAN’s dive accident and travel insurance plans provide additional coverage.

Third, if you have been away from the water for any length of time, treat each return dive like a chance to catch up with an old friend. Go slowly, and enjoy it.

Fourth, no matter how fit you are, accidents can happen. Be prepared, and practice for emergencies. Practice can prevent panic and create confidence. If you engage in vigorous exercise, learn to use a heart monitor. Get to know your maximum heart rate and recovery patterns. Unless you wake up rested at your normal resting heart rate, adjust your workout to match how you feel. Exercise is great, but know your limits.

Always stay informed. DAN is the go-to resource for current dive-related information.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021