British Columbia’s backyard fjord

With nearly 16,000 miles of rugged coastline and more than 40,000 islands and islets, British Columbia, Canada’s enviable wealth of ocean real estate, features fantastic marine life and spectacular coldwater scuba adventures. There is more here than you can enjoy in a lifetime.

Most local divers take their first giant strides in Howe Sound. Stretching 27 miles from its narrow head under lofty mountain peaks at Squamish to its wide-mouth opening into the Strait of Georgia just northwest of Vancouver, Howe Sound is North America’s southernmost fjord. This sea-to-sky corridor crafted by glaciers and perfected by time seems tailor-made for subsea exploration — reef and wreck, rec and tech.

Happy Hour at the Signature Site

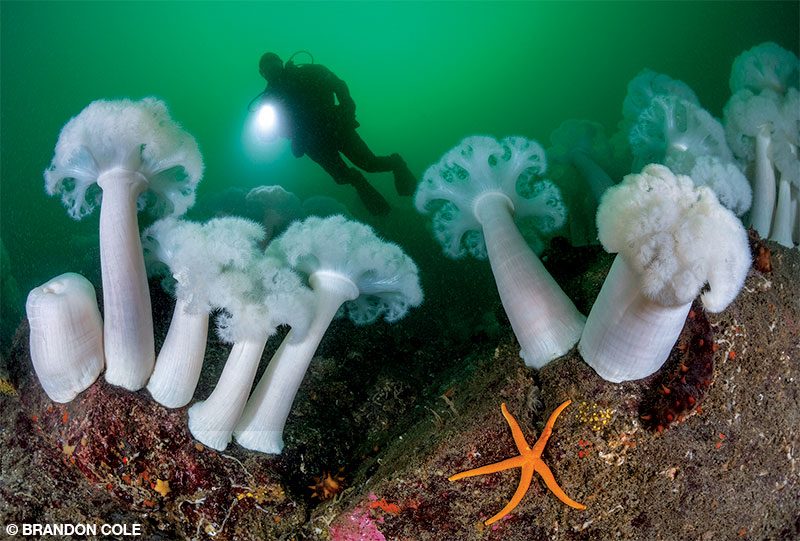

The most popular dive site in the greater Vancouver metro area is Whytecliff Park, where the high-rising fjord wall towers above and mirrors below the waterline. The site’s name is self-evident at 60 feet, where a field of snowy white plumose sea anemones spills over the edge of a wall that plunges 600 feet deep. Velcro-armed feather stars, blood stars, orange sea pens and armor-plated Puget Sound king crabs share space in the Metridium garden. Clusters of cloud sponge begin glowing at 85 feet. From a foot across to as big as a small car, sponge colonies light up the abyss beneath and function as critter condominiums. Tucked among the folds of the ivory- and butter-colored macaroni-like sponge masses are copper and yellowtail rockfish, spiny lithode crabs and squat lobsters.

But it’s not all steep and deep at Whytecliff. Inside the sheltered cove over a sandy bottom 15 to 40 feet deep, kelp and boulders provide habitats for shrimp, bulgy-eyed flatfish and blackeye gobies. Diving after sunset increases the odds of seeing nocturnally active sailfin sculpins, midshipman fish, giant Pacific octopuses and, in winter, stubby squid.

Divers of all stripes flock to Whytecliff Park, which in 1993 became Canada’s first saltwater marine protected area. This perennial favorite is busy year-round. New divers mingle in the shallows for open-water certification classes. Techies tricked out with rebreathers stealthily swim 10 minutes around the point to The Cut or straight out to the Day Marker to drop over the sheer wall. There’s also a third dive at Whyte Islet to the left. Some people swing by the park after work — dedicated divers will drive an hour from the crush of Vancouver city — to celebrate a serene happy hour with the fishes; others make a weekend of it, bringing a six-pack of cylinders. The park has restrooms, free parking, a rinse station and even a café. Air fills and gear are available from the dive shop in the nearby idyllic village of Horseshoe Bay. Whytecliff is shore-entry only. A garden cart is helpful to lug heavy gear between the parking lot and the beach below.

Sea to Sky Highway

Savvy locals also put wheels to work at Kelvin Grove in Lions Bay, schlepping their scuba kits by wagon or hand truck from automobile to ocean. Their reward waits around the point to the right. The top of the wall showcases purple sea stars piled up in a rugby scrum, orange and white sea cucumbers and schools of shiner perch. The middle depths are home to colorful or camouflaged red Irish lords, many kinds of nudibranchs (lemon, frosted, clown), kelp greenlings, buffalo sculpins and grunt sculpins. Reclusive beauties hiding in deeper crevices include the eel-like red brotula and boldly painted tiger rockfish. It pays to move slowly below 100 feet and carefully examine the openings of chimney and cloud sponges for decorated warbonnets or gunnels. This site can be very productive for macro photography.

Driving 8 miles north on Highway 99, the Sea-to-Sky Highway, brings you to Porteau Cove Provincial Park, another staple of Howe Sound shore diving, but with interesting twists. First, no mountain-goating is required; stairs provide quick and easy access to the sea. Second, the reef is steel, wood, rubber and concrete. Porteau is a curated collection of purpose-sunk ships (steel vessels still mostly intact and wooden ones now seriously deteriorated), a tire reef, heaps of concrete blocks and columns, and a jungle gym of metal H-beams.

Huge 75-pound lingcod, regally enthroned atop wreckage, lurk covertly in the shadows. Tunicates, bryozoans and crinoids glom on to the synthetic structures. Gobies and rockfish lounge about, and rumors abound of hidden wolf eel lairs. Surface buoys mark the main attractions, such as the 36-foot-long Centennial III dredge tender and the 92-foot Granthall, a steel tugboat later converted to a herring packer. Under its stern, 3-foot-tall plumose anemones hang like elegant, upside-down Easter lilies or luminous, living chandeliers.

Porteau Cove is an excellent place to practice underwater navigation while moving from feature to feature. Visibility is sometimes low, but modest depths ranging from 25 to 50 feet and the plethora of artificial reef structures deliver extra bottom-time enjoyment. But if the wind is blowing 15 knots or more — especially from the west or north — knowledgeable divers will postpone Porteau until a calmer day.

Heart of the Fjord

A boat is necessary for divers to see all of what Howe Sound offers. Charters out of Horseshoe Bay open access to the heart of the fjord, where dozens of stellar sites among the islands thrust up from the cool, emerald waters of this vast inland seascape. A 20-minute boat ride takes you to Halkett Bay Marine Provincial Park on Gambier Island’s southeast corner. Submerged in the protected bay lies the HMCS Annapolis, a destroyer-class warship intentionally sunk in 2015. The 366-foot-long Annapolis is the eighth addition to the Artificial Reef Society of British Columbia’s world-class ships-to-reefs program, enhancing both the recreational diving opportunities and the marine wildlife habitat. It takes many tanks to explore the mammoth wreck from bow to stern. It rests upright in the sand at 110 feet, but much of its structure is between 50 and 80 feet, with everything meticulously prepared for diver safety. There are no entanglement hazards, the hull and decks have numerous entry and exit holes, and there are three buoyed descent and ascent lines.

The Pinnacle off Bowyer Island’s north side is also a memorable experience top to bottom, but of the rock variety. Also called Wedding Cake, the site offers a range of profiles so divers can choose one appropriate to their skill level. The pinnacle’s tip peaks at only 15 feet below the waves, and deeper tiers fall away below. The layers of life include the usual profusion of anemones plus zoanthids, numerous crab species, giant nudibranchs and fish large and small, from lunker lings and wolf eels to tiny gruntlings. Don’t ignore piles of empty clam shells and crab parts. These messy leftovers hint that a well-fed octopus lives nearby. Bowyer’s East Wall serves up a variety of jellies — fried egg, lion’s mane, moons and more — that drift along its precipitous drop. Canyons, on Bowyer’s south side, earns five-star reviews for its diverse mix of terrain (sheer wall, rocky ridges and sandy gullies) and a smorgasbord of fish and invertebrate species.

Five miles farther into the sound, where the fjord narrows on its northerly snakelike path, Anvil Island has a handful of sites around it that locals and visitors alike rank among Howe Sound’s finest boat dives. Christie Islet offers a choose-your-own adventure from 50 feet to beyond 100 with nooks and crannies packed with creatures. It caters to both biologically minded divers who are keen to flex their marine-life identification skills and photographers who are obsessed with the quixotic pursuit of the perfect picture.

The strong currents that are a trademark of diving in much of British Columbia — and a driving force behind the ecosystem’s abundance — rarely limit underwater activities in Howe Sound. The waters can get moving at Dragon’s Den, but it’s often just a surface current, and sometimes there’s flow at depth. Experienced captains and divemasters assess the conditions and then thoroughly brief divers before opening the back deck. Once submerged, divers should carefully monitor and manage gas supply, time and depth and be ready to adapt to changing conditions. At this sometimes challenging, always exhilarating advanced location, stunning topography is the ticket. The wall angles back on itself, tilting past vertical to create magnificent overhangs with curtains of ghostly plumose anemones. For divers hovering in the shadowy void of these cavernlike recesses loaded with sea life but lacking a bottom, the view is a mindbender not soon forgotten.

Visit Pam Rocks for a change of pace and encounters with charismatic, whiskered megafauna. This cluster of islets south of Anvil Island is a haul-out site for harbor seals. Dozens are in attendance in the summer, luxuriating like flippered couch potatoes on rocky perches just above the waterline. Snorkeling is the best way to interact with the seals. Let them slip into the water and approach you when they are ready; with time, their curiosity will get the better of them.

Keep calm and marvel on. Look down to watch playful seals circling below you in the emerald sea; look up to be gobsmacked by the Coast Mountains soaring to kiss the sky. It’s a peerless view both above and below — the perfect Howe Sound half-in, half-out surface interval before the next dive.

How to Dive It

Conditions: Howe Sound is a year-round dive destination. The inland waters are sheltered from the open Pacific Ocean’s storms and swells, but strong winds can funnel through the fjord. Sea surface conditions vary from flat to rough and white-capped. There is always a protected spot somewhere to dive. Ocean temperatures usually hover in the mid-40°F range at depth and up to 52°F at the surface. Thermoclines and freshwater layers may be present, especially after heavy rains and snowmelt in the interior. Drysuits allow you to customize undergarment thickness to your thermal tolerance.

Water clarity is generally best during late fall and winter, when visibility is usually between 25 and 75 feet. Plankton blooms can reduce visibility in spring and summer, but divers may find better water clarity beneath a murky surface layer. A few sites experience current, and divers should exercise care, preferably diving around high or low tide. In general, however, Howe Sound does not require diving during slack water like many other British Columbia sites. The weather above the waves varies widely, from sunny and warm to cool, rainy and windy.

With a full gamut of dive sites — deep walls, shallow bays, muck dives, shipwrecks, seamounts and pinnacles — there are spots suitable for divers of all skill levels and interests. Many sites have deep water well beyond recreational limits, so proper training, planning and good buoyancy control are essential.

Getting there: Horseshoe Bay, the gateway to diving Howe Sound, is a suburb of West Vancouver and about a three-hour drive from Seattle, Washington, or one hour from the center of Vancouver, British Columbia. Traffic and border crossings can increase transit times.

Explore More

See more of Brandon Cole’s images of Howe Sound in a bonus photo gallery.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021