More Than Thresher Sharks

About 7,641 islands in the western Pacific Ocean comprise the archipelagic state of the Philippines. The country’s waters are integral to the Coral Triangle and feature some of the world’s most incredible biodiversity and eclectic dive attractions.

From Anilao’s macro and blackwater subjects to Tubbataha’s vast coral gardens and from whale shark encounters common in Oslob and Bohol to the sardine aggregations off Moalboal, the weird and wonderful abound for those who do their research and know what to expect. (See tinyurl.com/alertdiver-philippines for an overview of the most iconic Philippines dive regions.)

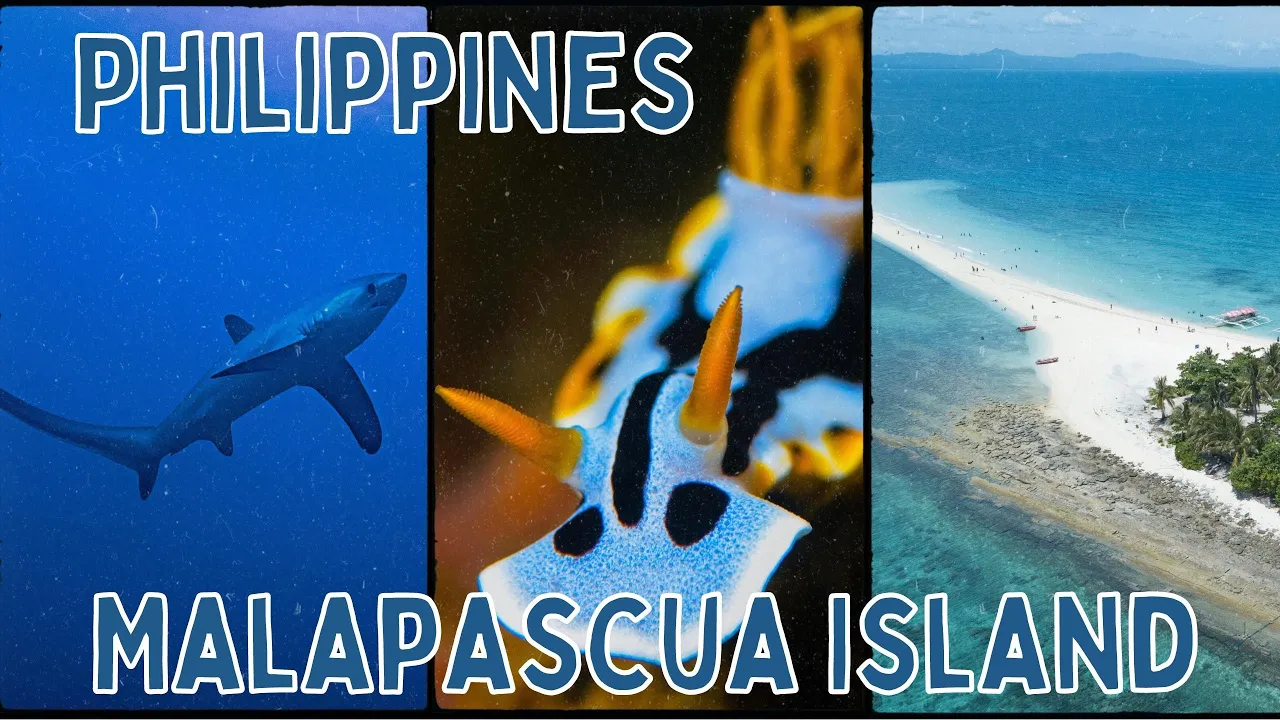

Malapascua is perhaps the most ascendant dive destination of all these locations. The island is synonymous with consistent thresher shark encounters, and while that is reason enough to visit, savvy dive travelers have recognized that Malapascua offers so much more.

Like many wildlife-centric destinations, it benefited from the absence of human activities during the COVID-19 pandemic. The ecosystem and wildlife concentrations flourished without dive pressure, but the consequence was that some marginal dive operations were lost to attrition. The operators that prevailed enhanced the quality of their services, and overall the tourism industry improved. Stakeholders came to understand that their well-being depended on conserving natural resources, and there was a noticeable difference in the diving after the pandemic.

My first trip to this tiny jewel of the Visayas Islands, one of the Philippines’ three major island groups, was in 2007, and it left me underwhelmed. Few subjects attracted my passion or caught my photographic interest. At a friend’s insistence, I returned to the island in 2023, and the changes were profound. The photo opportunities had improved, and so had the services that delivered them. Dive operators also seemed to better understand the region’s natural history. The experience had evolved so significantly that I booked my next trip before leaving the island.

What had happened in those 16 years? The most iconic attractions — the thresher sharks — were there in 2007, but divers would only see them starting at 100 feet (30 meters), dramatically restricting the time you could spend hoping for a close enough interaction for a great photo. Now you can see them in shallow water along with tiger sharks.

It is rare to be able to reliably encounter a thresher shark. There are other places in the world where you might catch a glimpse of one, but Malapascua is unique. Seeing multiple threshers there is a predictable daily occurrence in the morning when they approach known cleaning stations. Threshers are elusive and harmless. You can identify them at a glance from their saucer eyes and long, sweeping scythe-like tails.

The sharks’ behavior and locations changed during the two quiet pandemic years. Before then, they were often at Monad Shoal, a submerged island rising from the seafloor 656 feet (200 m) below and topping out at 66 feet (20 m) from the surface. It may not sound too deep until you are settled near the sandy bottom, watching your no-decompression time slip away while the sharks are maddeningly distant.

When the threshers moved to the nearby but much shallower Kimud Shoal, it was speculated that it was not because the human pressure was absent. Tiger sharks, which are more aggressive predators and several links higher on the food chain, chose to regularly patrol Monad Shoal during the same time. The threshers likely moved away for self-preservation. Kimud has a flat reef top that is much smaller than Monad, but the sharks are at only 33 to 50 feet (12 to 15 m), so you can do longer and safer dives with more ambient light.

Shark Encounters

Wide black eyes and a pointed snout define a thresher’s head, while the side profile is significant for the elongated tail and iridescent silver and streamlined body. I’ve been endlessly fascinated simply observing the slender animal, with its long tail swiping calmly in midwater like a snake on the sand and its sides catching and reflecting the natural light like a mirror. They use their tails for propulsion and to stun prey with a whiplike motion.

Thresher sharks are not easy to approach closely. You must be patient and remain quiet, staying almost stationary and hovering horizontally or on a fin-pivot. Stay disciplined against the desire to follow the mesmerizing tail movement, breathe softly and regularly, and hold your breath when they approach. The sharks eventually become more confident and may come very close.

Thresher shark numbers have increased, thanks in part to divers maintaining a healthy distance from cleaning stations. Divers must respect the sanctity of the cleaning stations. If the reef is in ruins from diver pressure, there will be no habitat for the cleaner wrasses, and without the cleaner wrasses the thresher sharks will leave for other reefs less favorable for Malapascua day trips.

The tiger shark’s vertical stripes along its side ensure you can’t confuse it with any other shark. These animals are strong and dexterous, with blunt, squared heads and glassy, inquisitive eyes. Mature females can reach about 18 feet (5.5 m) long. Monad Shoal is the more productive site for tiger sharks, but encounters there are more random than the virtually guaranteed thresher encounters at Kimud.

Thresher and tiger sharks are typically nocturnal predators, but at Kimud and Monad Shoals you can see them at sunrise and during the early morning hours. Sometimes thresher sharks breach completely out of the water, often when they are hunting sardines. Tail-slapping is an effective strategy for hunting schooling prey, but errant fin strokes sometimes propel the sharks above the surface. These pelagic sharks normally inhabit the deep seas, so it is truly special to encounter them on a reef at recreational depths. You won’t forget the surreal and magical experience, and you won’t get it anywhere else. That’s what makes Malapascua so special.

After the early morning encounters with the sharks, you can spend the rest of the day diving among the nearby sites’ various corals and marine inhabitants, which include gray bamboo sharks, whitetip sharks, snake eels, seahorses, nudibranchs, sea hares, lionfish, mantis shrimp, and all sorts of crabs. Malapascua has dozens of dive sites, including walls, wrecks, and colorful seamounts and pinnacles.

Seamounts are biodiversity hotspots, and the thriving underwater ecosystems off Malapascua are a diver’s dream, where colorful and intricate coral gardens provide a kaleidoscopic backdrop for a wide variety of marine species. It’s best to explore these areas with a skilled guide whose sharp eyes and environmental conservation ethos will enhance your experience. The right guide will prospect among red and yellow sea fans to reveal pygmy seahorses, spider crabs, mantis shrimp, squat lobsters, and harlequin and zebra crabs.

Slightly larger reef creatures, such as puffer fish, juvenile batfish, cuttlefish, banded pipefish, imperial shrimp, orangutan crabs, and flamboyant cuttlefish, are also familiar sights. The diversity of Malapascua’s marine creatures is astonishing.

Mandarinfish — a bucket-list species for many underwater photographers — are present at Lighthouse Reef. Dive to see them around sunset, when their courtship and mating behavior begins, with the male performing to impress the female. Taking a decent picture of these shy fish without disturbing them is challenging. Just as you think you have the rhythm of the encounter locked in, they abruptly stop and hide in the reef until the next night.

Gato Island, nestled in the expansive sea separating Malapascua and Carnaza islands, has at least five unique dive sites, including Whitetip Alley for sleeping whitetip sharks and The Guardhouse for pygmies. The residents at Nudibranch City are likewise evident from the name.

The tiny island is only 1.6 miles (2.6 kilometers) long, with no cars and only bicycles and motorbikes. Pristine sandy beaches offer sunrise and sunset views, and the local bars and restaurants provide a bit of sustenance in this tropical paradise. Above the water, the rocky small islet is home to numerous seabird species; below, it is a protected breeding ground for sea snakes.

I did two dives and was amazed to see sleeping whitetip sharks and frogfishes as numerous and diverse as nudibranchs. My dive guide’s sharp eyes also delivered cuttlefish, seahorses, lobsters, and cleaning shrimp.

Gato is so unique that the municipal government of Daanbantayan funded the construction of an outpost that plays a significant role in protection and conservation by deterring illegal fishing activities and protecting the marine reserves in the area. The Philippine Coast Guard and Bantay Dagat (sea patrol) staff this outpost to prevent unlawful activities at sea and ensure visitors’ safety. Marine biology students are encouraged to conduct biodiversity conservation research on Gato Island.

Dive Developments

The first dive operation to offer the thresher shark dive in Malapascua started in the late 1990s. Monad Shoal became a marine protected area (MPA) in 2002, and in mid-2015 Monad Shoal and Gato Island were designated as the Philippines’ first shark and ray sanctuary. An amendment to Cebu’s Provincial Fisheries and Aquatic Resources Ordinance in 2014 penalizes catching, possessing, and trading all shark and ray species there.

The MPA is 0.7 square miles (1.8 square km) with a 1,640-foot (500-m) buffer zone at the shoal’s outer edges. Visitor fees help fund the installation of mooring buoys and sustain local artisanal fishers. The conservation organization Save Philippines Seas has supported training former fishers as patrollers to enforce fishing regulations. Law enforcement in Malapascua is a community volunteer network that has worked with the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources since the 1970s.

After Typhoon Haiyan (known as Super Typhoon Yolanda in the Philippines) hit in 2013, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) based in Malapascua were founded to protect and conserve the marine ecosystem. They often use a community-based approach by supporting locals in becoming more ecologically and economically resilient. In exchange, these communities play a fundamental role in the NGOs’ research by providing valuable data for their research and analyses. Collaboration with the NGOs helps communities feel involved, better understand the issues, and make decisions accordingly.

Many of the island’s families have cultural, traditional, and emotional links to the ocean. Some make their living from artisanal fishing, while others derive their income from tourism and diving. In both cases, it’s in their interest to protect the ocean and its apex predators, such as sharks.

Thresher sharks are among the most demanded shark species for global fisheries. Their meat is prized for its high quality, their long fins for shark-fin soup, their livers for vitamin extraction, and their hides for leather goods. While there have been local efforts to protect these animals at the regional level within the Philippines, no agreement exists to protect them beyond boundaries, which is concerning because both species follow transboundary migration routes.

The Thresher Shark Research and Conservation Project has endeavored to promote ecotourism. Their comparative cost-benefit analysis, which shows that the value of divers observing live thresher sharks outweighs the sharks’ value in a fish market, has drawn favorable responses from conservation agencies and policymakers alike. Many efforts are underway to preserve the unique encounters that make Malapascua a special place to dive.

How To Dive It

Getting there: Malapascua lies off the northern tip of Cebu. To get there, take a flight to the Manila Ninoy Aquino International Airport, where you can connect to the Mactan-Cebu airport. From there, drive for about four hours (depending on traffic) to the coast, where you will take a 30-minute boat ride from Maya Harbor to Malapascua. When crossing from Cebu to Malapascua, make sure you get to the ferry dock at Maya Harbor well before 5 p.m. to board the last ride of the day. Before leaving Cebu, get some Philippines cash since most ferries, cabs, and local vendors will only take pesos. Several Philippines liveaboards also include Malapascua on their itineraries.

Conditions: You can dive all year in the Philippines, but the best conditions are during the dry season, from November through April. The Visayan Sea is calm during the entire season, but the visibility is best from late February to May. The water temperature does not change much and is typically between 80°F and 82°F (27°C and 29°C) year-round. Currents are generally nonexistent at the sites close to shore, but they can be moderate to strong at the seamounts and offshore islands.

The days are often hot and sunny from June to September, with rainy late afternoons and evenings. Jellyfish season also happens during this time, so a full-length wetsuit is advisable. Typhoons are possible between May and October.

Thresher sharks are present year-round, but the island can get crowded during the busy holiday periods, such as Christmas, Chinese New Year, and Easter.

Explore More

See more of Malapascua in this video.

© Alert Diver – Q1 2025