Have you ever seen an anchored sailboat with wetsuits and regulators hanging from the rigging and wondered what it was like for those divers? While there are benefits of living aboard and diving from your own boat, there are challenges as well.

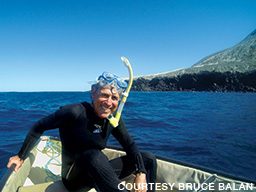

Today we are anchored at San Benedicto in the Islas Revillagigedo — one of the premier dive locations in the world, especially if you love friendly oceanic mantas. A couple of dive boats are anchored nearby after arriving from Baja California 300 miles to the north, each with a load of 15 to 25 divers. But some days we are alone. Diving in a group is much different from enjoying the quiet serenity when it is just you, your buddy and the big blue, which are the times we cherish.

Migration, our 46-foot trimaran, has been our only home for more than 15 years. We’ve sailed 60,000 nautical miles and visited 26 countries, and we feel truly fortunate to live this life despite the challenges. Just like being on a liveaboard, we must be completely self-sufficient. The two of us are responsible for everything, including ensuring we have adequate food, fuel, electricity and water to sustain our living and diving needs.

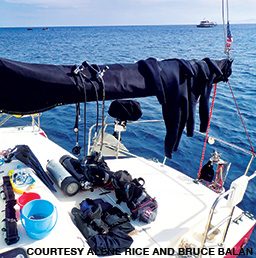

While many sailboats carry compressors, Migration does not because of the expense, maintenance, space and weight it would require. We usually have four tanks but had eight for our time at Revillagigedos, where the commercial dive boats were very kind about filling them for us. We usually get our fills from a shore dive shop or trade meals for fills with other sailboats. We also carry a DAN Dual Rescue Pak Extended Care oxygen unit as well as plenty of spare dive and boat gear.

We don’t need huge quantities of fuel, so we can go where few other boats do. We love anchoring for weeks at an uninhabited island to discover unknown dive spots and get to know the local fish. Sometimes we can dive right from our boat, but it may take hours to find a safe place to anchor. If drift diving is the only option, we tow our dinghy on a 100-foot rope so it will be available when we surface. The dinghy is equipped with a VHF radio, flares and water, even though the nearest person may be hundreds of miles away.

We must always create backup plans in case things go awry. There’s no Zodiac on the surface to rescue us if the current sweeps us away. We dive conservatively, constantly monitor our situation, and use our compass and underwater features to stay aware of where we are and the location of our boat.

Is it worth it? There are times we wish for a crew to grab our gear, fill our tanks and cook our meals. We limit our dives to once or twice a day, both for safety and because it takes a long time to rig, clean and break down our gear — especially with a limited water supply. There’s no hot tub or long showers. And there’s the ever-present uncertainty of being alone should something go wrong. We acknowledge that a severe dive accident will most likely be fatal.

Every adventure has risks. That’s one of the reasons it’s an adventure. But we can wake up in our own bed, don our gear at sunrise and slip into the sea to spend an hour alone underwater with mantas, sharks and dolphins — it’s worth it.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2020