Ask a buddy to name a bucket-list Pacific dive destination, and Canada is unlikely to be the first word out of their mouth — but it should be. For divers lucky enough to live in the Pacific Northwest, the local diving isn’t just decent and convenient but truly phenomenal. It is not only world-class for a coldwater location, but it also has some of the best diving to be done anywhere at any temperature. A visit to God’s Pocket Marine Provincial Park in British Columbia, Canada, is worth experiencing wherever you live, local or not.

Planning a visit there starts with some essential truths. The water temperatures are typically 44°F to 54°F. You will want to be in the water as much as possible, and time will chill you as much as temperature, so it is essential to be an experienced, well-equipped drysuit diver. Marine life fills most of the water, so you need to be perfectly weighted and trimmed because everything you swim around is alive, just as on a coral reef. Strong tides dominate the diving, and a highly experienced local guide is fundamental.

Despite being landlocked on three and a half sides, British Columbia is heavily fjorded. The coastline is packed with islands and inlets, making it more than twice as long as the coasts (including tidal areas) of Washington, Oregon, and California combined. The area has plenty of dive sites, but God’s Pocket is the almost unanimous choice for the top spot.

This marine provincial park shares its name with an off-the-grid dive resort, and locals also use the term to refer to the highly concentrated dive locale around the offshore islands at the northern end of Vancouver Island, near the municipality of Port Hardy. What makes this area stand out among all others in British Columbia are the dozen or more stellar dive sites, each as good as the best you will find elsewhere. Some sites are quite close together yet still highly diverse.

The waters are regularly calm, visibility is decent for temperate diving, and there is little sign of people. The forested coastlines come right to the water, and wildlife abounds. Bald eagles watch from the trees, and you can pass surface intervals marveling at humpback whales, playful sea lions, and adorable sea otters cracking mollusks on their chests.

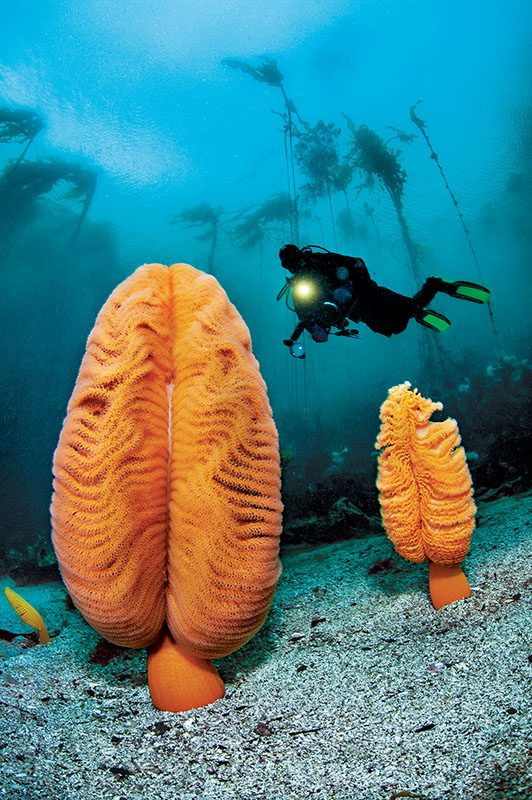

The location reminds me of Indonesia above the surface. The flat sea dotted with forested islets takes my mind to Raja Ampat, while the narrow strait, with dive sites starting beneath overhanging branches, reminds me of Lembeh. The destinations share similar reasons for their undersea richness — the landscapes concentrate the currents, and the rich water provides a never-ending buffet for the packed marine life. A difference, however, is that the nutrients and oxygen in British Columbia’s cold water help the endemic species grow supersized. Giant stalked anemones are as long as your leg, purple starfish are as big as car wheels, and even the bright-orange nudibranchs grow to the size of a shoe.

A major attraction of temperate waters is the usually present seaweed or kelp layer above a more colorful, invertebrate-dominated layer, meaning most spots offer two dives in one. Most dives here usually add another tier. I start most dives deeper, hunting for iconic species such as giant Pacific octopuses and wolf-eels, which typically live below 80 feet, where the terrain flattens out at the base of the walls. Going shallower brings you to the richest and most colorful life on the vertical surfaces — soft corals, sponges, hydroids, anemones, barnacles, and more all squeeze together. Crabs, shrimps, nudibranchs, and many fish species sit on top. Photographers can delight in the pile of subject upon subject without the need to swim to a new location.

When I can’t take any more color, I move shallower into the kelp forest. Large schools of fish gather between the stems, and the sun dances through the blades, revealing their golden hues. This is usually the most beautiful part of the dive when the sun is out.

The area’s most famous site is Browning Wall, a precipitous rockface totally plastered in colorful life, with pinkish-red soft corals, sulfur-yellow sponges, and white anemones. The lower diversity of life than a tropical reef creates more attractive scenery with a simpler primary color palette. The vertical wall prohibits seaweeds, so the gaudy invertebrate carpet begins just below the surface and is fully patterned from 30 feet onward. This living substrate provides a home for many critters, especially decorated crabs, nudibranchs, and small sculpin fish.

My favorite dive site is Seven Tree, named after a rock in the strait that once had seven trees but now has somewhere between two and a dozen, depending on how you classify trees versus bushes. My love for this site stems from it being a perfect dive: Multiple habitats are perfectly paced for a drift clockwise around the site. I start on the outside wall, which is nearly a match for Browning Wall’s technicolor spectacle. Next, I float through the kelp forest amid the fronds that glow golden in the sun and shelter rockfish, greenling, and hundreds of stiletto shrimp. On the backside I explore a shallow, sandy seabed before returning to the island’s small wall, which is thick with bright-red soft corals. I finish my dive back in the kelp.

At Clam Wall, Aquarium, and Snowball, we encounter multiple giant Pacific octopuses, although I inevitably always have a macro lens when they are out and performing. The octopuses vary in size — some can grow huge, but most here are mid-sized, about twice as big as a common reef octopus, although you can occasionally meet a big one. They are known to steal cameras and intimidatingly poke their suckers everywhere, especially any exposed, warm skin on your face.

We saw juvenile wolf-eels on Browning Wall, but the adults are out at Fish Bowl and Fantasy Island. Wolfies are at their most monstrous as adult males. They start as handsome youngsters with an orange and brown honeycomb coloration, but the adults’ old-man faces leave me struggling to think of another species whose youthful beauty deteriorates so much as they age. They are very long, so photos of their faces don’t always give an accurate impression of their dimensions.

Hooded Nudi Bay is another favorite spot, and thousands of Melibe nudibranchs covered the kelp there during my September visit. Hooded nudibranchs are large and feed by holding their hoods into the currents, closing them, and feeding on any particles they capture.

The area is excellent for macro subjects, and I love searching for decorated and mosshead warbonnets. The mossheads, also known as pricklebacks, are somewhat like overgrown blennies adorned with elaborate plumes and cirri above their faces. The sculpins have diversified to fill many of the niches that other species occupy elsewhere in the world. Scalyhead sculpins are like cheeky blennies, longfin sculpins remind me of a triplefin, sailfin sculpins resemble a dragonet, and red Irish lords, a favorite of photographers, are much like scorpionfish.

For me, rockfish are the classic fish of these dives. They are large and often gathered in groups, and many of the species are colorful. Canada’s government has created rockfish conservation areas along the coast to conserve the 37 species of these slow-growing fish living in British Columbia’s waters.

The tides dominate the days here, making different sites good in narrow windows throughout the day when the tidal currents slow, stop, and then reverse at slack water or when a particular current direction creates a lee or reversed eddy. Detailed local knowledge is essential for unlocking the diving potential in terms of spectacle and safety. The resorts also live by the tides and change their wake-up, breakfast, and dive times each day so divers are ready for the ever-changing tidal moments. While this sounds complex, it ensures that the whole group is relaxed and prepared to hit the right spot at precisely the right time.

It can be bizarre to begin kitting up for a dive while watching a fierce current tear at the water’s surface and jellyfish whooshing past the rocks. But as I finish climbing into my gear, the kelp forest pops to the surface as the algae’s buoyant bladders overcome the drag from the diminishing current. When I hit the water, there is just a mild tug from the tide that stops within the first few minutes.

After about 45 minutes of a technicolor marine life assault on the retinas, the tide begins to pull the other way. By now I am shallowing up into the kelp forest’s protection, and I finish the dive sheltered within this three-dimensional wonderland. There is no underestimating the power of this ocean and the spectacle. God’s Pocket isn’t my local diving, but I wish it were.

How to Dive It

Getting there: God’s Pocket is nearly 300 miles from Vancouver, so most locals pack all their gear and travel by car, catching a ferry to Vancouver Island. Visitors from farther away can fly to Vancouver or Seattle and rent a car for the trip. It is possible to fly directly into Port Hardy from Vancouver by light aircraft, but there are baggage restrictions.

Conditions: Good dive conditions do not persist year-round. Winter is too stormy, and summer brings thick plankton blooms, leaving spring and fall as the main seasons. The water is cold (44°F to 54°F), especially considering the repetitive dive schedule. The visibility varies from 30 to 100 feet, mainly depending on plankton blooms and storms. Tidal currents determine the dive schedule and site availability, so planning a trip over neap tides is desirable.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2023