When did you start diving?

I got certified in 1992 on the Great Barrier Reef in Queensland, Australia. For the next five years I dived in Turkey, Thailand, and on the shipwrecks of Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, Scotland — all over the place. In 1997 I completed instructor training at Bass Lake in South Africa and then started teaching in Wales, where I lived. My wife and I moved to Western Australia in 1999, and I opened a diver training facility at the local boat dealership. Life was pretty good for a few years, and I issued more than 500 certifications from basic open-water diver to technical decompression diving.

It was quiet in the winter there, so I went back to university and earned a bachelor’s degree in training and development. After that, I spent another two years researching dive injuries while earning my master’s degree in public health. I then closed the dive business to focus on dive research, and around that time I took up cave diving.

Where did you complete your doctorate?

In 2005 I asked the late Richard Vann, Ph.D., if I could work on my doctorate with him, but I wanted to stay at the University of Western Australia (UWA). After some discussion, he decided that splitting my program between two universities would not work, so in 2006 I started at UWA. In 2007 Vann invited me to apply for a DAN internship. My application was successful, and he collected me from the airport in late May.

There were quite a few of us interns that year, and we all trained to collect data for Project Dive Exploration (PDE). After a week, the others flew to various dive destinations, and I remained at DAN with Erin from South Carolina and Alex from Colorado. We worked on projects at the DAN office or Duke University during the week and went diving on the weekend. Alex and I did 135 dives in six states that summer. Our first observational study showed that the no-decompression limits in dive computer user manuals were not a reliable guide for how conservative the computers were likely to be for diving in lakes at high altitudes.

What did you do after the internship ended?

I returned to Western Australia and continued collecting data for PDE — more than 1,500 dive profiles in all. Meanwhile, I dived, usually in caves, and then I finished my doctorate and presented my findings at the European Underwater and Baromedical Society meeting in Istanbul, Turkey. The Norwegian professor and dive researcher Alf Brubakk, M.D., Ph.D., was one of my examiners, and he chaired the morning session before I presented my results. I was nervous, but a month later I learned that he passed my thesis with only minor corrections.

By then I was certified to dive trimix with low oxygen levels (hypoxic trimix), which I used for diving very deep caves. I spent the next couple of years diving mines in Sweden, sump diving in Polish caves, and exploring the giant, water-filled caves 300 feet (91 meters) under the Nullarbor Plain, an immense limestone plateau on the southern coast of Central Australia. That is where I currently dive.

How did you end up in Europe?

After finishing my doctorate, I was wondering what to do next when I received an email inviting me to apply for a two-year postdoctoral fellowship in decompression research as part of the Physiopathology of Decompression (PHYPODE) Project at the Université de Bretagne Occidentale in France. On Christmas Day 2012, my wife and I arrived in Brest, France. The university did not reopen until January 4, which gave us a couple of weeks to explore.

On my first day, I walked to work carrying a small French-English pocket dictionary, counting my steps along the way. “Une, deux, trois.” By the time I got to work, I could count in French.

What were you doing there?

The work was fascinating, and François Guerrero, Ph.D., was a delight to work for and very demanding. He would encourage us to aim higher, submit our results to better journals, and make the most of every opportunity that came our way. I mentored three doctoral students — one researching cultured cells, one decompressing rats, and one using human subjects. In addition to helping them, I looked at population-level epidemiological data. This time in my career was highly productive, and I made some dear friends with whom I still work.

I cave dived all over France and northern Italy on weekends and holidays. Other trips took me to lakes in Germany, shipwrecks in Croatia, flooded buildings underneath Budapest, and mines in Belgium, Slovakia, and a few other countries. I even won a research grant to visit Brubakk’s lab in Norway. While there, I flew to Rana, Norway, and dived in the arctic Plura Cave.

Between all this diving, we worked on our interests in decompression sickness’s genetic determinants. We imagined what it would be like if we had a test that could tell us if someone’s genes were upregulated and they were peaking in terms of protection right before a big dive. We designed a selective breeding program and bred a strain of rat that was highly resistant to decompression, and this work continues.

What did you do next?

As this wonderful time ended, Petar Denoble, M.D., D.Sc., offered me a position at DAN. My wife and I sold our home and moved to North Carolina. It was fantastic — I published a lot of dive research over the next few years and made a lot of dives spanning 20 states. DAN sent me to give talks at dive shows and dive clubs, which I really enjoyed. I gave 32 presentations in my last year at DAN. The dive clubs were the best. I’d give a talk to a packed room, and then we’d go for dinner somewhere. I’d end up at a table with people who had been diving all their lives. There could be 150 years of dive experience at the table, and the plentiful dive stories came out fast, especially if you mentioned the “old days.”

Meanwhile, I was the DAN Annual Diving Report editor, and I was running the DAN Internship program. I had come full circle. During my time at DAN, I published a few epidemiology papers I still consider among my best work. I worked on estimating the risk of dive injuries in recreational divers, which is still my focus. Everyone else — military divers, dive scientists, etc. — has someone closely looking after them, but recreational divers are a fascinating bunch.

Where are you now?

In July 2018, after three and a half years at DAN, I accepted an offer at Curtin University in Perth, Western Australia. Now I am the director of graduate research, which means I help all the master’s and doctoral students stay on track. I also teach one unit, applied paramedic bioscience, which I really enjoy. The rest of my time I spend on my own research, by which I mean my doctoral students’ research.

I still collaborate with researchers outside my university. Last year I won the DAN/Alfred Bove Research Grant, which I am using to establish a wet lab in our new hyperbaric chamber facility. We have doctoral student researchers studying bubbles and cardiac function in recreational divers and plan to add a third to look at nitrogen narcosis. The grant is an excellent opportunity to grow a new generation of dive scientists.

What’s left that you want to discover?

There is one big question I haven’t yet answered but would like to: Does diving add to our life expectancy or reduce it? I’m also interested in whether deep vein thrombosis in commercial airline passengers is a form of decompression sickness and how we can identify recreational divers who are prone to bubbles after diving. I can’t pin it down for you — there is too much in the world that holds my interest. There just aren’t enough hours in the day.

I never looked back — I still do both kinds of work. I get to switch from basic science in the lab one day to being an attending physician in the emergency department the next, and I’m delighted with how things have worked out.

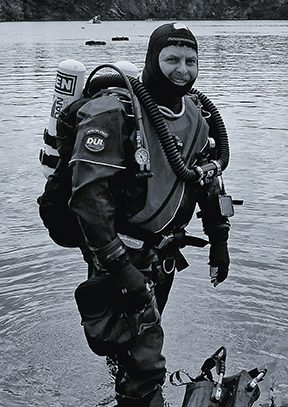

Photo: Courtesy of Peter Buzzacott

© Alert Diver — Q2 2022