DAN medical information specialists and researchers answer your dive medicine questions.

I recently took DAN’s online Basic Life Support: CPR and First Aid and Emergency Oxygen for Scuba Diving Injuries courses. I’ve heard it is best to put an injured diver in the recovery position on their left side because of the possibility of a patent foramen ovale (PFO). Is this true, and what would be the benefit?

A PFO is undoubtedly a concern with diving because about 25 percent of the population has one. The recovery position supports and maintains an open airway in an unconscious person or injured diver. The left-side preference was based on anatomy, not PFO concern. Blood from the venous system returns to the right atrium via the superior and inferior vena cava, so the idea of putting a diver on the left side was to alleviate unnecessary weight that might compress these large vessels and impede circulation.

Recent studies and recommendations from the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation (ILCOR), however, suggest there is no benefit to placing someone on their left side instead of their right side when using the recovery position. In the case of suspected decompression sickness (DCS), place the injured diver in a position of comfort, or if they are unconscious, one that allows you to monitor them as necessary.

PFO concern is not a factor in this case. If the diver is symptomatic and you are rendering care, then you need to treat the symptoms. Give them the highest concentration of oxygen available, and get them to definitive health care and treatment. Remember that many conditions show symptoms that may mimic DCS. Just because someone was diving does not mean they have a dive-related illness. When creating your emergency action plan, note the location of the nearest emergency room or where and how to access local emergency services.

— Robert Soncini, NR-P, DMT

Can someone be certified to dive if they were born with “little ear” — where the ear wasn’t fully formed in the womb and the canal didn’t open?

It seems like you are referencing both microtia and aural atresia. Microtia ranges from minor changes in the outer-ear shape to a very small external ear, possibly with no external canal or eardrum. Anotia is the complete lack of any ear structure, and aural atresia is the absence of an ear canal.

Your physician may not necessarily restrict diving. The concern would be making sure your anatomy allows for proper equalization of your Eustachian tube and any potentially remaining gas in a vestigial middle ear. If equalization is impaired with gas still in the ear, you could risk barotrauma (a pressure injury) on your functional internal ear. If this is not an issue, then the risk would be severe barotrauma on the other fully functional ear, which could cause deafness in rare cases.

A physician might suggest you avoid diving if your hearing is already unilateral, since a dive injury to the functional ear could result in bilateral hearing loss. Consult with your ear, nose and throat specialist to discuss your ear anatomy and determine if diving is possible.

— Brandi Nicholson, MS, EMT-P

My doctor said that my blood cells (white, red and platelets) are immature, and at times I have very high counts, although they are currently within the normal range. Will this condition impact my body’s ability to get oxygen to my cells and eliminate nitrogen? Will I have a higher risk of DCS or bubbles forming in my blood?

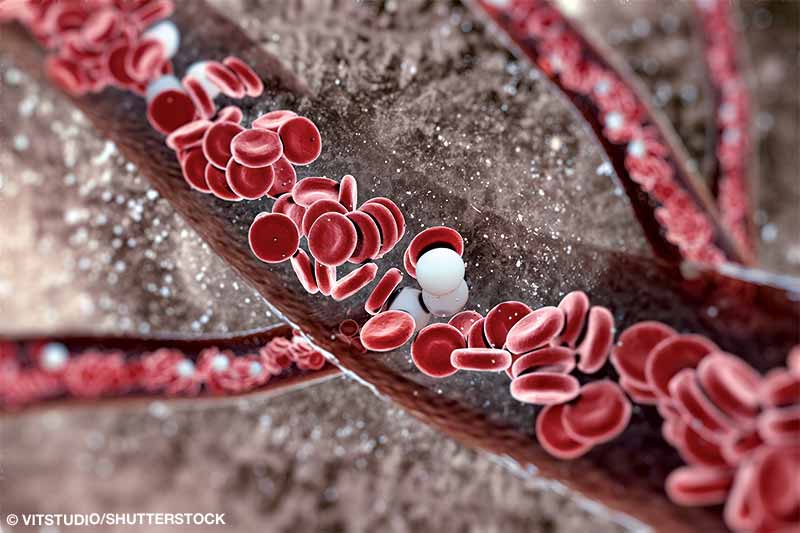

The condition you are referencing can be a type of myelodysplasia. The body’s long bones, including the sternum, humerus and femur, produce new blood cells. A disruption in the bone marrow can release immature blood cells into the body.

The World Health Organization classifies myelodysplasias into subtypes based on the types of cells involved. If two or three cell types are abnormal, it is a multilineage dysplasia. In this condition blood cells will die in the bloodstream soon after being released or while still in the bone marrow. Over time, there will be more immature cells than healthy ones. Complications can include opportunistic infections, fatigue and abnormal or uncontrolled bleeding.

Platelets are components within our blood responsible for beginning clotting. Decreased platelets will inhibit clotting, which may lead to uncontrolled bleeding. If you have bleeding from blunt or penetrating trauma, barotrauma from difficulty equalizing, or DCS, you may have uncontrolled bleeding that could go undetected for some time.

Diving exposes you to bacteria and other microorganisms in the water. White blood cells are the body’s natural defense mechanism against these contaminants. Immature or inadequate white blood cells may lead to opportunistic infection or, if your immune system is compromised, a serious illness.

Red blood cells carry oxygen and other nutrients throughout the body. Immature red blood cells are unable to meet the body’s oxygen demands while diving. This lack of oxygen may lead to fatigue, the possibility of passing out and potentially drowning.

Diving often takes place in a remote location, and access to immediate or definitive health care may be difficult. When planning a dive trip, ask the dive operator or resort about access to health care and their emergency action plan for caring for an ill or injured diver. Some locations may have more limited medical care than others, especially if an air evacuation is involved.

— Robert Soncini, NR-P, DMT

I have a history of atrial fibrillation (AFib) and had a cardiac ablation to restore my heart’s normal rhythm. My recovery went well with no complications, and I have returned to normal activity. Is it safe for me to dive now?

Opinions vary in the dive medicine community about AFib and medical fitness for diving. Some physicians completely recommend against diving, while others are more permissive. Respected dive medicine cardiologist Dr. Douglas Ebersole believes that AFib alone, with an otherwise structurally sound heart (confirmed through treadmill stress testing and an echocardiogram), should not prevent diving. As long as you control your AFib with medication and have proper exercise tolerance, you should be able to dive.

Your successful ablation has resolved the dysrhythmia issue of AFib, but it raises another concern. The ablation procedure may have required a transseptal puncture to get the catheter from the right atrium into the left atrium. This puncture results in an atrial septal defect, which will generally heal without any intervention over time. Unfortunately, there is no clinical definition of how long that time is. Although the hole is typically small, depending on the exact procedure (some catheters are larger than others), you would be at risk for bubbles shunting from the right to left atrium until the hole has completely closed.

The best recommendation is to wait for confirmation from your cardiologist that the hole is closed before you return to diving. An echocardiogram with a bubble study is usually the procedure to determine the hole closure.

— Lana P. Sorrell, MBA, EMT, DMT

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2021