Deep in the silent oblivion of the Adriatic Sea off the coast of the Croatian island of Svetac, Lorenz Marović and his son, Andi, found a series of historical treasures: the remains of two U.S. Army Air Forces planes that foundered during World War II and the wreck of the Greek steamship Michael N. Maris, which sank in 1932.

The divers had persevered for months before ever leaving the dock, studying relevant nautical charts and analyzing reports of local elders. Once ready, they equipped their boat with a powerful towed side-scan sonar and began to conduct hydrographic surveys. The energy emitted by a side-scan sonar sweeps the seafloor directly underneath the “towfish” and laterally more than 300 feet outward in each direction. The strength of the return echoes is continuously recorded, creating an image of the ocean bottom that’s clearly visible on a screen on the boat’s bridge. Local fisherman aided Marović by providing guidance based on their experience working the Adriatic.

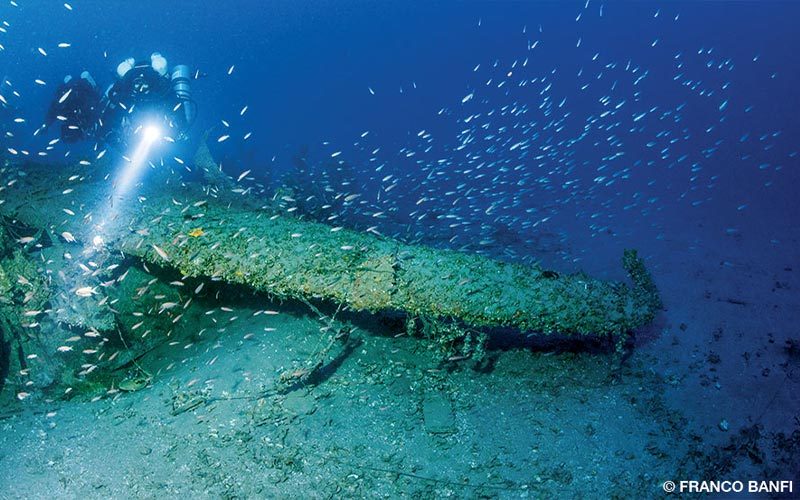

One day the sonar monitor showed something resting on the bottom of the sea. The second part of the expedition thus began, as they planned a series of technical dives to verify what the sonar had shown. I joined their group of professional divers and technicians at this time with the goal of documenting these exciting discoveries.

Tom Baier, three tech divers and I met to plan the dives in detail. We would be using closed-circuit rebreathers and bailout tanks filled with trimix (helium, nitrogen and oxygen) for the deep sites (200–360 feet). This would allow us to safely maximize our time spent at depth so we could collect as much documentation of the wrecks as possible. Thoroughly planning the dives is a key element in ensuring the success of such an expedition. Nothing can be ignored, and redundancy is mandatory — even if it means heavier equipment and more time spent studying best practices and worst-case scenarios.

For the first day of diving in September 2016 we chose a site where we had seen signs of an airplane’s remains resting on the bottom at 310 feet. Looking at the monitor of the sonar, we were excited to see the clear shape of wings and part of a fuselage. We were eager to take the plunge, to go where no one had been before us, and to break the silence of forgetfulness by bringing to the surface knowledge of the events that caused the sinking. We felt the excitement of the discovery, but after a few minutes we had to control our enthusiasm and remain calm.

Taking pictures at 300 feet is not an easy task for the camera gear or the photographer, who must simultaneously leverage extensive knowledge of both technical diving and photography. Working under more than 10 atmospheres of pressure requires all divers to have a clear plan and a goal in mind. Nothing can be improvised; there is no time to experiment with settings to find the right one through trial and error.

Though we had only 25 minutes on the bottom, we spent more than 130 minutes doing decompression stops at various depths for a total dive time of more than 2.5 hours.

In those 25 minutes, however, we photographed in detail a PBY Catalina aircraft that sunk Sept. 12, 1944, during an attempt to rescue five survivors from a very rough sea. The survivors were the crew of the Consolidated B-24H Liberator #41-28762 Tailwind, assigned to the 515th Bomber Squadron of the 376th Heavy Bombardment Group, 15th Air Force in San Pancrazio, Italy. On Sept. 12 the crew participated in a raid on Munich, Germany, that focused on the Allach BMW Engine Works. That day the Allach engine works and the Wasserburg aircraft factory were assaulted by nearly 330 Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberator heavy bombers supported by P-38 and P-51 fighters.

On the return flight to San Pancrazio, the rudder control of this B-24H failed; the plane dropped out of formation and began a slow left turn due to a tail flutter. The crew, ordered to bail out, parachuted into the middle of the Adriatic about 50 miles north of the island of Vis. An intensive rescue mission was launched. Despite high swells and strong winds, the captain of the PBY Catalina succeeded in making an open-sea landing and taking aboard five survivors. But the aircraft could not take off — it began to fill with water and was abandoned. Its crew and the men they had rescued were picked up by a British Landing Craft Infantry (LCI), an amphibious ship, and taken to safety on Vis. Another air rescue saved two additional members of the bomber’s crew, while the remaining four crew members were never found.

The well-preserved remains of the PBY Catalina are now part of the sea. Though the plane’s tail is lost and some of its lower portion is partially buried in the sand, most of its features are easy to recognize even though the aircraft is totally covered by encrusting marine life after 72 years in the Adriatic Sea.

In accordance with Croatian law, the wrecks’ finders declared their discoveries to the appropriate government and military authorities, and it is now forbidden to dive the sites. After the required surveys and recovery, the site will be opened to the public to dive under permits given to dive centers in compliance with Croatian law.

| © Alert Diver — Q1 2017 |