Legendary researcher and champion of dive safety

A U.S. Navy SEAL, a respected researcher of decompression theory and an expert in hyperbaric and dive medicine, Richard D. “Dick” Vann (1941–2020) had an extensive career spanning more than 60 years. His work contributed to the implementation of safer pressure-exposure protocols in diving, mountaineering and space exploration.

After graduating from Columbia University in 1965 with bachelor’s degrees in liberal arts and mechanical engineering, Vann worked as a dive engineer at Ocean Systems Inc., where he developed his passion for dive physiology and safety as he learned about decompression sickness (DCS), decompression tables and the engineering of decompression procedures. An enthusiastic scientist, he volunteered in his own experiments, including experimental chamber dives to 650 feet.

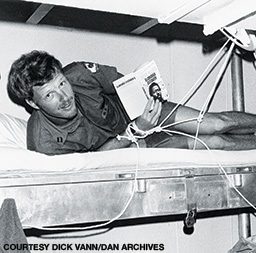

In 1967 Vann began service in the U.S. Navy, completing Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training and serving as a platoon commander and dive officer for Underwater Demolition Team 12. After four years of active duty he remained in the Navy Reserve, leading research and naval special warfare units until retiring as a captain in 1997.

His scientific interest in diving, space and high-altitude physiology led Vann to earn a doctorate in biomedical engineering at Duke University in 1976. He was an assistant professor in the Department of Anesthesiology at Duke Medical Center from 1976 to 2010 and spent much of his career at the Duke Center for Hyperbaric Medicine and Environmental Physiology’s F.G. Hall Environmental Laboratory, where he served as engineering safety officer, chairman of the Operations and Safety Committee, and later as director of applied research.

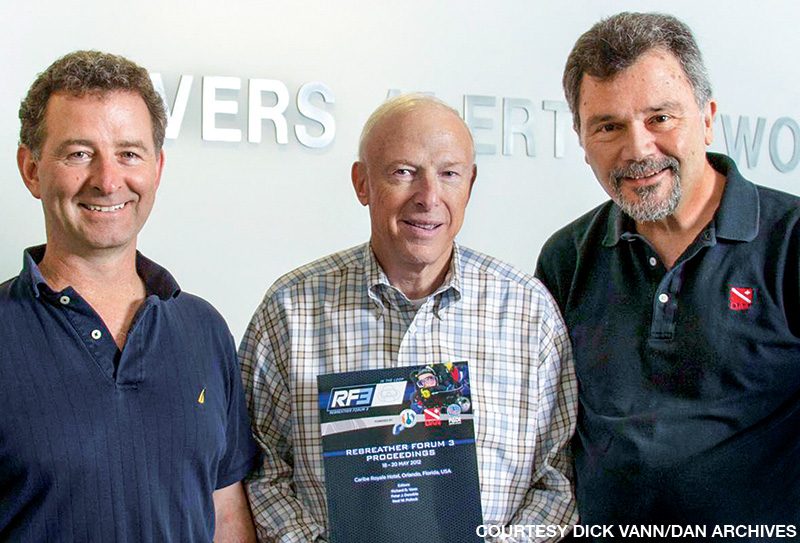

In 1990, as interest in recreational diving was increasing, Vann started working with Divers Alert Network® (DAN®) and founded the organization’s research department. As a director and later as vice president of research, he led studies of dive safety and injury prevention for more than 20 years.

Extreme Environments

“Significant events in history do not occur at random. They occur because individuals confront problems and have the ingenuity and motivation to find solutions,” Vann wrote in his 2004 article about scuba, rebreather and operational physiology pioneer Christian Lambertsen. When Vann joined the field of diving and environmental physiology in the early 1970s, researchers had already established the scientific foundation of safe dive operations. Coming from an operational background, however, he identified possible problems, confronted them with ingenuity and persevered until their resolution.

Combining his dive experience with his training in engineering and environmental physiology, he explored various aspects of safety in extreme environments at the F.G. Hall Environmental Laboratory, a large hypo/hyperbaric complex with a history of studying human limits. Influenced by his time in the Navy SEALs, who can be exposed to extreme exposures such as hypoxia (too little oxygen) and hyperoxia (too much oxygen), Vann studied the effects of breathing hyperbaric oxygen on cerebral blood flow, cerebral oxygenation, cognitive performance and central nervous system oxygen toxicity as well as the effects of elevated oxygen partial pressure on narcosis caused by carbon dioxide (CO2). On the other extreme, he studied the effect of hypercapnia (too much CO2) on arterial oxygen saturation and cerebral oxygenation during hypoxia.

He also studied respiratory functions in hypobaric and hyperbaric conditions combined with hypoxia and elevated CO2 in animals and humans, with interest in optimizing oxygen-delivery equipment for diving, sea-level and altitude activities. His breath-hold studies included the dynamics of oxygen and CO2 changes in breath-hold diving and the effects of hyperventilation and oxygen prebreathing on freediving.

Vann’s decompression research drew upon his experience in deep diving as well as his engineering drive to quantify each phenomenon he studied: bubble location, underlying mechanisms, physical conditions leading to bubble occurrence, and the amount of inert gas that dissolves in the body during dives. He also was involved with the development of decompression tables, advanced modeling of decompression disease risk and prophylactic procedures to mitigate DCS risk while providing the necessary time for efficient operations.

To develop safe decompression procedures Vann acknowledged the necessity of direct human experiments with a possible outcome of DCS. These studies included deep saturation diving with heliox, saturation diving with nitrox, use of surface interval oxygen breathing to enhance repetitive diving capabilities, safe postdive surface intervals before flying, special forces operations involving flying after diving and parachuting from high altitude, and safe decompression mitigation for space walks through exercise.

Vann was also interested in closed-circuit breathing apparatuses for diving and for normobaric first aid oxygen delivery. His numerous laboratory and field studies greatly contributed to the safety of closed-circuit rebreather diving.

“I have never met a mind as good as his; I have never met anyone as active and engaged in the research as Dick was,” said Carl F. Pieper, associate professor of biostatistics and bioinformatics at Duke. “He wanted to not only understand the structure of the research but also try it out and even add to it. In the end he often challenged me — in my area of expertise! He was the model of curiosity and learning.”

DAN Research

Vann had a huge influence on DAN’s early success and impact in research. He initiated complex dive safety studies such as Flying after Diving and Project Dive Exploration and conducted early analyses of dive injuries and fatalities, which led to DAN’s ongoing Annual Diving Report. He mentored other researchers such as Donna Uguccioni, whose study under his guidance introduced the optional safety stop for dives within the no-decompression curve.

An early DAN field study showed that the venous gas emboli (VGE) count is highest after the first day of diving and decreases with successive days of diving. Despite great variability of postdive VGE, it appeared that older divers generate more bubbles. The risk of DCS appeared low, however, and no participants experienced DCS. Due to the low incidence of DCS and high variability among recreational divers, researchers concluded that any field-based DCS safety study would require a large number of dives, which led to Project Dive Exploration (PDE) in 1998.

By initiating the DAN Summer Research Internship program, Vann engaged young people in dive science and invited them to assist with data collection for PDE. The program welcomed its 100th intern in 2019.

Project Dive Exploration. In general, recreational divers are older, less fit and more likely to have chronic illnesses than the U.S. Navy subjects who volunteered for experiments leading to the development and testing of Navy decompression tables. The availability of dive computers with recording capability allowed for a real-life study to test concerns that Navy-based decompression procedures may not be suitable for recreational divers.

In this observational study of dive exposure and outcomes in recreational diving, DAN collected dive profiles and physiological parameters of almost 200,000 dives over 13 years. The PDE study determined the risk for DCS is 3.4 per 10,000 dives, despite variables between different groups of divers and diving environments. It also showed that Navy decompression models overestimated DCS risk in most recreational diving — more so in leisurely diving and less in more arduous coldwater, deep-wreck diving.

Flying After Diving. To establish evidence-based guidelines for the waiting period before flying after diving, Vann and his colleagues started a first trial in which they were also test subjects. They began with a short preflight surface interval that was the Navy standard at that time and after a 60-foot dive decompressed themselves to the flight cabin pressure equivalent to 8,000 feet. No one developed DCS, so they exposed volunteers to a flight six hours after diving, hoping to repeat the experiment enough times for a statistical confirmation of safety. The first experiments with a six-hour interval, however, resulted in one subject getting mild DCS that resolved completely upon recompression.

Vann and his colleagues designed a new series of experiments that included repetitive dives and started with long surface intervals and strict criteria that had to be met before the experiment could proceed with shorter intervals. After 812 subject exposures and more than 20 cases of DCS, this experiment provided evidence-based guidelines for flying after diving that Navy and recreational divers use today.

Additional studies for the Navy indicated that reducing the dive time or depth could drastically shorten the wait time after a single dive. These were dry (chamber) and resting dives, however, so the results were not directly translated into a practical guideline.

Dive Accident Monitoring. DAN is the only entity that collects and monitors dive incidents and fatalities worldwide, and Vann furthered this effort. Submitted voluntarily by divers (anonymously if preferred), the reports are a large part of the Annual Diving Report and provide an opportunity to learn from the mistakes of others, to determine equipment issues that occur and to derive preventive strategies for future dives. This huge endeavor eventually led to the creation of DAN’s Department of Injury Monitoring and Prevention.

A few months before Vann died in April 2020, he communicated his thoughts about a new research project following the roots of PDE but including newer technology to capture larger and more precise datasets on physiological as well as epidemiological aspects within the dive community. Such forward thinking garnered Vann much respect among his peers. Friends and colleagues remember him as an excellent lecturer, he was published in numerous publications, and he mentored many young people toward successful scientific careers.

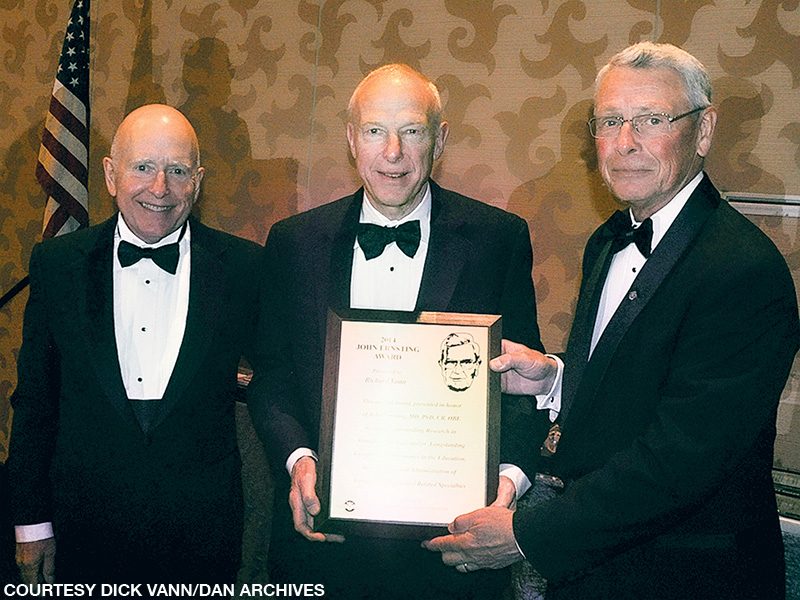

His many awards and honors include a U.S. Navy Commendation Medal; the Oceaneering International Award (now Excellence in Commercial Diving Award) from the Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society (UHMS) in 1992; the UHMS Excellence in Diving Medicine Award in 2003; the Beneath the Sea Diver of the Year for Science award in 2007; Johnson Space Center’s Group Achievement Award from NASA in 2011; the UHMS Albert R. Behnke Award in 2012; the Aerospace Medical Association’s John Ernsting Award, the Academy of Underwater Arts and Sciences NOGI Award for Science and a EUROTEK Media Award in 2014; and the Reaching Out Award for Science and Research from the Diving Equipment and Marketing Association (DEMA) in 2015.

Vann’s colleagues will remember his friendly and kind personality, his endurance in both research and exercise, and, according to Petar Denoble, M.D., D.Sc., DAN vice president of research, “his willingness to put his body where he asked others to take risks.”

“Dr. Vann was a distinguished mentor and role model,” Denoble said. “He was also an exceptionally kind man with a big heart. His contributions to dive safety are truly unmatched, and I am grateful I had the opportunity to work alongside him for so many years.”

“I will be forever thankful for the wisdom Dr. Vann imparted to me,” said Matías Nochetto, M.D., DAN director of medical services, “and I am humbled to have also witnessed his humility, generosity and perennial smile. He will be fondly remembered by all of us who knew him at DAN, and his contribution to science will continue to inspire generations.”

Explore More

Dick Vann received DEMA’s Reaching Out Award in 2015 and was honored with this video.

© Alert Diver — Q3/Q4 2020