A destination in disguise

I feel a surge of excitement as our boat approaches Santa Catalina Island (better known simply as Catalina) for a three-day dive trip. I’ve dived here hundreds of times and savored some of the best encounters of my life in these waters. But even as I’m noting the familiar topside crags and crannies that mark some of my favorite dive sites, I’m struck by a realization: This is the first time I’ve joined a multiday charter with Catalina Island as the only objective. I’m not sure why I waited so long.

Californians — and not just divers — know Catalina well. It’s right there off the coast, gleaming just 22 miles in the distance. On clear days we steal glances at its graceful curves as we drive down the highway. Knowing it’s easily within reach, we take it ever-so-slightly for granted. We can hop a ferry over there on any given weekend, so there’s no real sense of urgency to do so right now. Local divers attend the waters around this island on at least a semiregular basis: It’s an easy ride over there, plenty of day trips from the mainland are available, and there’s nearly always a protected site to dive. Still, many of us don’t visit it for more than a quick trip. That acquaintance and proximity ironically seem to get in the way.

Even if you’ve never set foot or scuba tank on Catalina — heck, even if you’ve never visited the West Coast — you’re probably acquainted with this island. It has appeared in hundreds of movies, although in true Hollywood style it’s occasionally dressed up to resemble some very non-California locales. Catalina is featured in its full au naturel glory as the current backdrop image of a certain well-known computer operating system. Sports fanatics may recall that Bill Wrigley once owned both the island and the Chicago Cubs and that the Cubs’ spring training took place on Catalina for nearly 30 years. Even if you’ve picked up an occasional dive magazine and appreciated a photo of a beautiful kelp forest, there’s a good chance you’re admiring a shot captured at one of Catalina’s reefs.

Well, familiarity be damned. For the next three days I’m going to reframe my thoughts and view Catalina as what it is: an incredible destination that just happens to be near my home. After all, I’m visiting a beautiful island that rarely sees rain, where unspoiled nature encompasses huge expanses and which boasts some of the most spectacular dive sites in North America.

Day 1: The Pretty, the Angry and the Exceptionally Large

When the captain anchors at Little Farnsworth, we know we’re in for a treat. One of the highlight dives of Catalina, this offshore pinnacle rises from the seafloor (115 feet at the absolute shallowest) to reach a minimum depth of 55 feet. Although the wide-angle opportunities here can be stellar — with angel sharks in the sand below the pinnacle, gorgonians and anemones encrusting the spire itself, and pelagic invertebrates passing by in the water column — I’m a bigger fan of the macro life, especially the nudibranchs. I’m aware that admitting such partiality can be polarizing (divers seem to be very black or white on sea slugs), but I can’t help it. They’re just so pretty.

I grab my macro rig and hop into the water with my eyes peeled for a glimpse of one of these colorful critters among the Corynactis anemones and zoanthid corals that seem to blanket every surface. It’s not long before I’ve hit the jackpot, finding a cobalt blue, yellow-spotted Felimare californiensis crawling over the reef, looking like a cartoon that has come to life. I spot several more slugs, including some of my most-wanted species — a pink-and-orange confection called Babakina festiva and a pair of bright-pink Okenia rosacea — before it’s time to take my exhilarated (and slightly nerdy) self back to the boat.

When the boat anchors for our next dive at Long Point, the first thing we notice is that a current is running past the site. There’s always a little current running around Long Point, but today we can visualize the water movement from the boat, with telltale ridges marring an otherwise glassy surface. The divemaster briefs us accordingly, reminding us that boat traffic around Catalina can be heavy and encouraging us to carry surface signaling devices as a precaution.

I jump in and kick into a strong current to get around the point into the bounds of one of the island’s marine protected areas. I pass a few small beds of kelp here and there, but the rocky reef is the real draw. Dozens of spiny lobsters boldly peep at me from the ledges, and a school of mackerel swirls overhead. But the garibaldis here steal the show. With nesting season well underway, these bright-orange members of the damselfish family are feisty, rushing my dome port and prompting jokes back on the boat about “the attack of the angry goldfish.”

We next request an unusual dive for a boat trip: Casino Point, which includes the famous Avalon Underwater Park. Abutted by the picturesque Casino building (which encloses a vintage theater and a ballroom but not a gambling establishment), this dive park on the outskirts of Avalon is all about the water. Protected since 1962, the park is a 2.5-acre underwater fantasyland that attracts divers of all shapes, sizes and experience levels, who gather here daily to make the easy shore trek down a wide set of stairs into the ocean. It’s telling that multiple memorial plaques are present within the park’s perimeter (including an imposing one dedicated to Jacques Cousteau), providing tributes to divers who had a meaningful connection to this area.

Scattered rocky reefs hold spiny lobsters, moray eels, abalone and some of Southern California’s most common piscine residents, including garibaldis, sheepshead and kelp bass. For wreck enthusiasts, several sunken structures also lie within easy distance from the shore, although some are so crumbled now that they’re more rubble than recognizable. A small glass-bottom boat and a sailboat lie close to one another near the entry stairs at a depth of approximately 60 feet, and a schooner called the SueJac sits a bit further out at about 60 feet deep at the stern to 90 feet at the bow. If divers are willing to gain permission from the harbormaster and kick a bit further, the remains of the Valiant yacht lie just outside of the park perimeter and offer a more advanced experience with a maximum depth of 110 feet. Given the extra effort and boat traffic, this site is not visited as often but is worthwhile, with a host of invertebrate inhabitants and an easily identifiable bow that rises up from the sand.

Our interest here, however, isn’t wrecks. It’s the kelp bed in the center of the park, which is currently sheltering a crowd of very welcome residents: giant black sea bass. Only a few decades ago, these critically endangered fish were once hunted nearly to extinction, and it seemed like a too-little-too-late proposition when state fisheries officials finally passed a law protecting them in 1982. Against all odds, however, these rare, huge fish (they can weigh more than 500 pounds) have been increasingly easy to view in the Southern Channel Islands, especially during the summer months when they collect en masse for spawning — and doubly so at Catalina since the dive park has been their chosen gathering spot for the past few years.

As the only divers who’ve arrived here by boat, we attract and quickly shake off a few scornful glances from our shore-entry brethren as we gear up. I quickly forget my sheepishness as I come face-to-face with a duo of giant sea bass at 40 feet only minutes after I enter the water. While I hover in front of them with my camera at the ready, one of them utters a loud, threatening croak — a sound I take to mean, “Back off, pipsqueak.” I oblige, leaving them to their courtship, and continue to explore the kelp, counting off maybe eight more sea bass by the time I ascend. Knowing that they have gathered with the express purpose of making new sea bass is a wonderfully optimistic end to our first day.

Day 2: The West Side is the Best Side

We collectively let out a whoop when we see that we’re anchoring next to Ship Rock, a spectacular dive site marked by (predictably) a big rock shaped like a boat’s sail. This is a top choice of many locals even though the lush giant kelp forest that once defined the reef here was severely impacted during the warm-water events several years ago and has shown little sign of regrowth. Kelp or not, the marine life here is still incredible, and we’re lining up to get into the water the moment the briefing ends.

The reef here plummets from the surface to well beyond recreational depths. In the shallows, a few thick tufts of Sargassum horneri (invasive algae that have taken up residence in the area) poke up from between the rocks. Once I drop below 30 feet and head to my planned maximum depth of 100 feet, the rocky reef is increasingly punctuated instead with sponge-covered scallops, red gorgonians and elkhorn kelp. The usual reef denizens — occasional lingcod, moray eels and lobsters — can be spotted here, but the fish life is the standout feature in my opinion. Huge numbers of blacksmiths swarm over the rocks, making it difficult to inspect the deep plateaus for angel sharks and nearly impossible to watch the open water for other sharks and large pelagics.

Back on board the boat, we bypass nearby Bird Rock (although the barks of the boisterous California sea lions that have been increasingly populating the site are an extremely tempting draw) and motor westward toward Johnson’s Rock. The namesake rock here barely breaks the surface, but it’s just enough to aid with easy topside and underwater navigation. I descend through the kelp forest that dots this series of pinnacles and swim from boulder to massive boulder, exploring until I come across a large rock that displays classic California marine life. Large gorgonians (one or two covered with thick zoanthid corals) and colorful sponges encrust the surface, and blacksmiths and sheepshead gather around the perimeter. From between two sea fans, a large red scorpionfish waits patiently but fruitlessly for one of the smaller fish to become careless. While no exciting predation takes place on my watch, it hardly matters with plenty of color and action here to admire.

In the afternoon, the boat continues to move toward the far west end of Catalina, finally anchoring at Eagles Nest. There’s minimal need for the divemaster to announce the site; before we have even anchored, several divers are gathered on the deck, pointing out the eagle cam, a webcam that livestreams a view into the namesake bald eagles’ nest at the top of the cliff (iws.org/livecams.html). I’m watching the large, graceful birds circle overhead when something in the water catches my eye: A small harbor seal is checking out our group from a nearby kelp bed. Almost as soon as I get my hopes up, I begin to feel greedy. This site has gifted me with some of my most memorable encounters over the years — a frantic market squid run, close interactions with giant sea bass, bat ray flybys and even a swarm of brightly colored jellyfish. It seems too much to hope for that I’d have yet another spectacular interaction.

I kick slowly through the kelp forest, stopping to flutter my feet into the water column every so often (a seal-attracting trick I learned from a veteran British photographer). When I see one or two other divers watching my antics, I feel somewhat ridiculous — until the harbor seal tugs on my left fin. I manage to closely admire him and get a picture or two before he swims away, presumably to look for something tastier than my beat-up fins. For the rest of the day we admire the healthy giant kelp that dominates this site, observe the schools of mackerel and surfperches that weave past, search for topsnails and kelpfish among the leaves and watch the light rays glint through the canopy until they begin to dim.

Day 3: Rounding a Corner

It’s our last day, and a glum mood hangs over the galley (everyone knows that “last day” is synonymous with “abbreviated number of dives”). Typical for the departure day of any trip, the weather is perfect, and the water is calm, so eerily calm that the captain comes into the galley to discuss matters with us. “Here’s the deal, guys,” he says, “Normally we’d try to stay closer to home so you could get in more dives. But I haven’t seen it so flat in a very long time. If there’s ever been a day to visit the backside of the island, it’s today, even if we have to lose a dive to get there.” This is a no-brainer for our group, most of whom recognize that a placid dive day on the exposed side of Catalina is a rare and magnificent thing. The vote is unanimous: Quality beats the heck out of quantity. We motor across a glassy surface, marveling at the absence of waves on the shore as we pass the northwest corner of the island and head toward Farnsworth Banks.

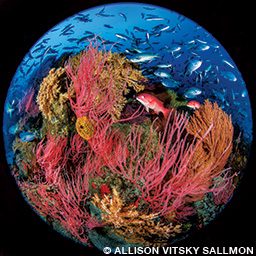

The uniqueness of Farnsworth can’t be overstated. A series of pinnacles that rise from deep water, this site is exposed to intense currents and bathed in rich nutrients. As such, it carries the attendant expectation of you-can-see-anything encounters. Jellyfish and other invertebrates are a given, and in past years I’ve witnessed some truly incredible stuff such as a huge school of barracudas, the switch of a retreating thresher shark’s tail or torpedo rays hunting in a dense swarm of blacksmiths. But that isn’t what makes this place unique. The singular, standout characteristic of Farnsworth is the thick cover of purple hydrocoral (Stylaster californicus), a lavender-hued lace coral that imparts a distinctly tropical atmosphere and coincidentally provides a gorgeous backdrop for photographs.

I descend through the disarmingly clear water, passing through a loose mishmash of pelagic invertebrates to reach the highest point of the pinnacle. Palm kelp sways gently over the shallowest point at around 50 feet, revealing layers of Corynactis anemones and bryozoans (and the occasional stealthy scorpionfish or two-spot octopus). As you drop over the edge of the pinnacle, there it is: a mass of purple hydrocoral. Other than a short stretch of wall covered by yellow zoanthid corals (tellingly dubbed the “Yellow Wall”), it’s a riot of lilac as far as the eye can see. The barest glance reveals spectacular finds among the hydrocoral: red and golden gorgonians along with cabezon, lingcod, moray eels, topsnails and nudibranchs. All too soon the morning of diving ends, and although we know it’s nearly time to head home, our group pulls together and clamors for just one more dive.

The captain rolls his eyes at us as he grins and agrees. He drops the hook next to Eagle Rock, a small, craggy peak that juts from the water, and we tumble in to explore the adjacent reef that spans from the rock to the western tip of Catalina. The dropoffs here are extremely fishy and covered with gorgonians, so most of our crew heads off to the deeper water. I hang back — the shallow rocky reef here is a personal favorite; divers don’t commonly visit it, which seems to make it a hotspot for local marine life.

In the past I’ve had great sea lion, guitarfish and torpedo ray interactions here, but today seems to be a horn shark day. These small sharks usually hide in the kelp detritus along the seafloor, but it doesn’t take long for me to spot one and then another swimming in midwater, turning away the second they detect me. With only a few minutes of diving left, I’m able to hold my breath until a shark gets to within a foot of me, and I simultaneously pull the shutter and exhale at once, sending one very startled creature back into the forest before I surface.

Now that the diving is over, I pack my gear as I admire Catalina Island’s retreating hills, and I know without a doubt that my next visit to this conveniently located site will be for more than a single day. That’s as it should be. Catalina, after all, is an incredible island destination: a beautiful, unspoiled place where precipitation is rare, pristine nature dominates and some of the most outstanding dive sites in North America are just offshore.

Interview with Dr. Bill: Catalina Island’s Resident Marine Biologist

You’d be hard-pressed to find a diver who knows Catalina better than Bill Bushing, Ph.D. The marine biologist, diver and underwater videographer commonly known as “Dr. Bill” has been an island resident since 1969. A frequent visitor to the dive park, he often provides detailed local dive reports and marine life observations to local social media outlets and produces regular newspaper and blog columns, peer-reviewed scientific papers and educational videos.

His influence goes far beyond the local dive community. He has provided critical expertise to numerous projects led by Jean-Michel Cousteau (including aiding Ocean Futures Foundation efforts and providing film support for Secret Ocean 3D). Dr. Bill is a lot like Catalina Island itself: Even if you haven’t met him, you’re likely familiar with some aspect of his work. I couldn’t think of a better person to speak with about the island he calls home.

Why Catalina? How long have you lived on Catalina Island, and what is your professional history there?

I arrived a little more than 50 years ago to teach marine biology at the former Catalina Island School (at Toyon Bay) for 10 years. Later I was a consultant to the Catalina Island Company and wrote many manuals for their tours. After receiving my Ph.D., I became vice president of the Catalina Island Conservancy.

What are the most impactful changes you’ve seen on the island, both topside and underwater?

There have been positive and negative changes. Topside, the creation of the Catalina Island Conservancy, which several of us suggested to the Wrigley family back in 1971, was a hugely positive step. In the marine world, positives include the recovery of giant black sea bass, white sea bass and California sea lions. On the negative side, I’ve witnessed the disastrous impact of the highly invasive Sargassum horneri (invasive algae) and the local near-extinction of blue sharks.

What is your one piece of advice for future stewards of Catalina’s ocean environments?

My dream future would be for them to find a way to eradicate Sargassum. Future stewards, however, should continue educating the general public about the kelp forests and other marine habitats so they will come to understand current ecological issues.

What is the oddest or most incredible marine life encounter you’ve had while diving the waters around Catalina?

There have been many, including working with Jean-Michel Cousteau to film the wonders of Catalina both topside and underwater. The incredible squid run we filmed in 2013-14 would probably be a major highlight.

You do hundreds of Catalina dives a year, in water that definitely requires exposure protection — and you’re known locally as someone whose wetsuit will almost be falling apart before it gets replaced. What is the longest-lived wetsuit you’ve had?

I have a wetsuit from the 1970s that’s still wearable when the water is warm enough. Some people think the reason I can bear the cold is that I don’t have a nervous system.

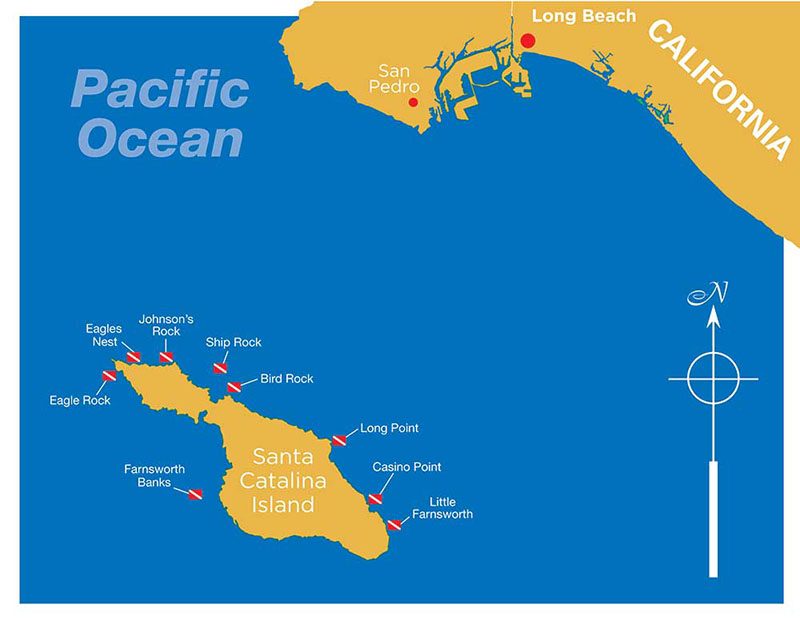

How to Dive It

Getting there: For those who want to pursue a land-based visit, ferries operate regularly out of San Pedro, Long Beach, Newport Beach and Dana Point. Gear rentals, guided dives and boat diving are available in Avalon and Two Harbors. A gear and tank rental facility is located directly adjacent to Casino Point. Single- and multiday dive trips to Catalina are widely available from coastal Southern California, with operators running from as far south as San Diego to as far north as Santa Barbara.

Conditions: Catalina is almost always accessible for diving, but optimal conditions are from late summer into early winter. Water temperatures vary from around 52°F below the thermocline in the winter to about 70°F at the surface during the summer; wear either a drysuit or 7 mm wetsuit with a hood and gloves depending upon individual dive plans. Visibility can range from 30 feet in the spring to more than 80 feet in the autumn and winter. Some of Catalina’s dive sites are appropriate for newer divers, and others are better suited for advanced divers. It’s best to disclose your certifications, experience and comfort level when booking to ensure an enjoyable trip. The presence of an in-water dive guide or divemaster is uncommon for many operations in California; if you prefer one, specify your request upon booking. A recompression chamber is present on the island.

Marine protection: In addition to the underwater park at Casino Point, eight other marine protected areas with varying levels of protection exist around Catalina Island. A detailed map that outlines specific restrictions is available at californiampas.org.

Topside: Tearing yourself away from the incredible diving here will be a challenge, but it’s certainly worthwhile. Catalina has a fascinating history, and the Catalina Island Conservancy protects approximately 88 percent of the island, including the longest undeveloped stretch of shoreline in Southern California. Topside activities are numerous and varied, ranging from camping, hiking, off-road tours and ziplining to spa treatments and high-end dining. For more information on lodging, activities and transportation around the island, visit catalinaconservancy.org and catalinachamber.com.

© Alert Diver — Q2 2020