The power and importance of America’s marine sanctuaries

The seas saved me. It started with a dive trip in 2015 when I was an unhappy lawyer. I found myself on the bow of a boat in a refuge so pristine and wild that it shook me to my core. The ocean stripped me bare and brought me back to life. I returned from that trip motivated to protect the water and all the life in it.

This journey eventually led me to reef restoration work with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary. In that turquoise sea, I connected with ancient corals and the people working to save them. Impressed by their courage and stubborn optimism, I realized again that oceanic sanctuaries revive more than marine life.

The U.S. currently has 14 national marine sanctuaries and two marine national monuments. Just like the people who live, work and play within them, they are all unique and special. In these wondrous places, one storyline remains the same: If we protect the place, it will give back tenfold.

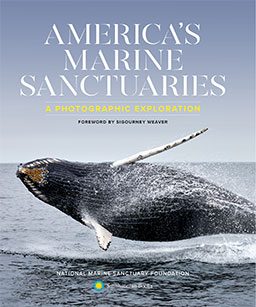

America’s Marine Sanctuaries: A Photographic Exploration, a new book by the National Marine Sanctuary Foundation (NMSF) and published by Smithsonian Books, highlights the sanctuaries and the resources they safeguard. The book anticipates the 50th anniversary of the 1972 National Marine Sanctuary Act, which kickstarted the national effort to defend our oceans and the Great Lakes. Through exquisite photographs and intimate details, the project celebrates the nuances of each sanctuary and monument and makes a case for why these places matter.

“For a long time, we forgot about the ocean,” said Kristen Sarri, president and CEO of NMSF, the nonprofit partner of the National Marine Sanctuary System. “Now we understand we won’t have a healthy planet or healthy communities without a healthy ocean.” Believing that photos help people “see beneath the waves” to understand what’s there and why it’s worth protecting, she enlisted the help of photographers living and working in these sanctuaries to tell the story.

“When done right, photography has a wonderful ability to connect people to something,” explained contributor Keith Ellenbogen, an underwater photographer with a conservation focus. “Images can convey a sense of wanting to go to a place, a connection to an animal or what makes something special.” Ellenbogen said his cover shot of a breaching humpback whale in Massachusetts’ Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary is his most spectacular because it showcases the animal’s relationship with the ocean. It evokes a sense of anticipation for diving down into the water and sets the stage for the book, he added.

Douglas Croft, whose image of a gray whale mother and calf in Big Sur, California, appears in the book, described the annual migration and its effect on him: “I sit on the cliffs in Big Sur in late April or early May, when the gray whale moms with calves keep close to the shore to avoid killer whales. Watching them swim by beneath me is a beautiful, spiritual thing. It brings me to tears.”

The curious calves love to play in the kelp and sometimes stop in a nearby cove to nurse before passing his vantage point. As he waits, Croft thinks about the protected areas in Mexico where the little ones are born and Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary, through which they migrate as they pass his camera lens. “The whales are now protected from whaling,” he said. “It’s such a testament to what happens when we decide to protect something instead of destroying it. We see new life coming in.”

Croft remembers when Monterey Bay was not abundant and healthy. The sardines were overfished, the otters were killed for their pelts, and the waters essentially became a desert, he said. After the sanctuary was established, the ecosystem recovered and continues to thrive under its strong protection.

It’s also an open fishery for crabs and anchovies and one of the world’s top markets for market squid. “Regulation ensures that resources won’t be overfished again,” Croft said. “It’s so vibrant now.”

As a deckhand on a local whale-watching boat, Croft still gets excited every time he’s on the water. No matter if it’s his first or 50th time seeing a whale breach, the phenomenon always takes his breath away. The experience changes people, he explained, because you can’t unsee it, and you can’t stop feeling what it does to you.

John Armor, director of the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries (ONMS), echoed that sanctuaries are much more than environmental strongholds; they also serve as economic and social catalysts, preservation tools and living laboratories for science. These national treasures have served the communities around them in multiple, important ways since time immemorial, he added. The National Marine Sanctuary System’s mandate is to defend these ecological, historical and cultural resources while promoting compatible and sustainable uses. To that end, specifically tailored, location-based conservation models ground each sanctuary.

“If people want to keep scuba diving on reefs, we need healthy reefs. If people want to dive on shipwrecks, the wrecks need to be preserved and managed,” ONMS chief economist Danielle Schwarzmann said. “The sanctuaries provide the infrastructure to do all that.”

This is precisely the case in the Flower Garden Banks National Marine Sanctuary (FGBNMS) off the Texas coast. Critical habitats underpin the local economy, so fishers take an active role in their preservation. “Accountability reduces waste” in the sanctuary program, said Scott Hickman, a Galveston-based hunting and fishing guide and chair of the FGBNMS Advisory Council.

Hickman innovated a win-win-win mechanism that operates in the sanctuary, simultaneously promoting fishing, supporting conservation and creating new ecotourism opportunities. Outdoor enthusiasts join commercial boats for free to have fun while helping fill orders from fish houses and learning how to protect the sanctuary’s rich biodiversity. The smaller boats avoid fishing techniques that damage the unique coral reefs and fish nurseries that sustain the entire ecosystem. The catch is harvested without labor costs. Overall, the “marketable experience” produces a higher-quality fish product for both local restaurants and ecotourists, and the entire program prevents overfishing — the problem that originally inspired Hickman.

“I ran charters for more than 30 years and got sick of throwing back dead fish that weren’t being utilized,” he said. “Now we keep what we catch, and we stop when we get enough for the order. I developed these programs for conservation, and their implementation helped bring back these fisheries and habitats.”

Sanctuaries build a culture of American pride in caring for something special, and knowing that places such as Flower Garden Banks will be taken care of and persist for a long time means something, Hickman said. Sanctuaries can also engage and enrich the communities around them. Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary (TBNMS) in Michigan is a prime example of the convergence of conservation, social dynamics and economics. The sanctuary’s designation 20 years ago preserved hundreds of historical shipwrecks, which arguably represent the greatest collection of shipwrecks in the world, said Stephen Kroll, a former Great Lakes dive operator and chair of the TBNMS Advisory Council.

It also reinvigorated nearby Alpena, Michigan, by creating a new business and tourism hub around the flourishing dive, snorkel and kayak industries. Much like how species naturally spill over from marine protected areas (MPAs) to nearby fishing spots, business boomed as economic spillover from protecting the historical resources. “That’s the heart of what sanctuaries do — bring together communities to thrive,” Sarri noted.

“In Alpena, the community now is the sanctuary, and the sanctuary is the community,” Armor echoed. “Protection and conservation are not exclusive from economic and community well-being. They are linked together.”

This synergy within the sanctuaries is a motivating factor for Armor, who pushes all people to understand that they are stakeholders in the system. “If we do our job right,” he said, “it’s not just future generations that can enjoy these places and historical resources, but current communities and generations also benefit.”

For many indigenous and native communities, this past, present and future connection to the environment is foundational to their culture and identity. “The traditional way of life relies upon a healthy ocean,” said Kalani Quiocho, Native Hawaiian Program Specialist at Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in Hawai‘i. “We are an extension of our place; if the place is healthy, we are healthy, and vice versa. Similarly, if we take care of the ocean, the ocean will take care of us.”

The sanctuary incorporates these viewpoints into its management. Quiocho works with management agencies to “figure out how culture can exist in some in-between spaces” and enhance the work the sanctuary does. Papahānaumokuākea, one of the world’s largest MPAs, has species Quiocho doesn’t see on the main islands and large predators that his ancestors knew and worshipped. More than that, it protects the cultural role that the reef has played in native creation stories and that it still plays in present-day culture. It’s important to sustain these ties to heritage and place. Quiocho described the first time he stepped foot on Nihoa (an island within Papahānaumokuākea), chanting the words of his forefathers while experiencing the same things they did when they accessed the island — the smell of guano, the hot sun on his skin, millions of birds and the sea spray. The familiarity of this “ancestral experience” transformed him, Quiocho admitted.

“It felt like this is where we came from, our roots, when we were still close with the sharks,” Quiocho added. “We talk about endangered species and essential habitats. I feel like Papahānaumokuākea is that for native Hawaiians — a place where we can be Hawaiian at the core, to our bones.”

The protected area serves as a portal for Hawaiian communities, ensuring that they remember its importance and allowing it to inform their decisions, he said. Protecting and connecting with such a sacred place allows Quiocho and others working within the sanctuary program to manage the waters in ways that restore both culture and nature.

Each protected area has its own unique story and incredible strength, Sarri said. In preserving these irreplaceable resources, the sanctuaries protect who we are at our base — our soul as a nation. They reaffirm us and connect us to our incredible heritage. They revive us and fill us up.

“Sanctuaries are like food for our soul,” Armor said, quoting Rear Admiral Tim Gallaudet, deputy administrator for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). “There are the things we talk about — ecological, historical, economic, the measurable things that point to a sanctuary — but what you can’t measure is the impact of these places on your soul. I have felt it, and it has changed me.”

Sanctuary protections also have a ripple effect on ocean conservation in general, with ideas from the program, such as permanent mooring buoys and community advisory councils, gaining traction globally. Indeed, America’s marine sanctuaries can serve as sentinels for the wider seas, showcasing how we can move toward protecting enough habitat to ensure the ocean’s future and our own.

Many invisible forces threaten our waters. From climate change and water quality to accessibility issues and popular relevance, the challenges are numerous. They are of our own creation, which means that they are also ours to mend, Sarri said. It is our responsibility to act as stewards to protect the beauty and resources that lie within our oceans, Great Lakes and beyond.

These wonders belong to all of us and connect us to the seas, Sarri concluded in the book. The ONMS holds these special places in trust for current and future generations, ensuring that they — and we — can and will endure.

Explore More

Watch this video to learn more about the U.S. National Marine Sanctuary System and its upcoming 50th anniversary.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2021