It’s easy to recognize French Polynesia’s softness: the fragrant leis, the gentle strumming of ukuleles, the coos of loved-up couples and the curved sheen of bewitching black pearls. But it’s important to look past these things if you really want to get to know this South Pacific paradise, which is defined far more by its contrasts, such as the craggy corners of coral atolls, the tattooed graphics that adorn the limbs of the locals, the juxtapositions of every conceivable blue hue where the lagoons meet the open ocean — and the angular fins and toothy smiles of the three tiger sharks that are lazily circling us in the sapphire-colored distance.

Tahiti

Our guide has pulled out the big guns for our first dive, White Valley, and he seems quite pleased with himself. “It’s all about the sharks,” he informed us as we moored at this site, a reef that slopes to a rubbled channel at 65 feet and then sharply drops off into the blue. Instructions are simple: Hunker down next to the channel, and wait for sharks to show up.

Almost immediately, expectant gray reef and lemon sharks began swimming past us; minutes later the big guys show up. Their conditioning around divers is a remnant of the regular feeding that occurred here before recent local regulations banned the practice. The piscine politics are clear, with smaller sharks slowing deferentially whenever a tiger shark passes overhead, which is often. I glance over at the guide, who points enthusiastically toward the smallest of the tiger sharks, a male I estimate to be 12 feet long. He flashes me an animated, extended OK sign, so I smile weakly and signal OK back to him, quickly turning my attention back to a particularly large gray reef shark who seems overly interested in her reflection in my dome port. After 40 minutes or so of controlled chaos, the tigers depart one by one.

Our ascent from White Valley presents a wind-whipped surface, a bouncing dive deck and a captain eager to find some calm inside the lagoon. The Spring fortunately offers a placid, protected haven despite the wind’s antics. Cold, fresh spring water feeds this series of coral-covered, anemone-topped pinnacles, creating a thermocline — and a shimmering silver visual effect — in areas of outflow. The extra boost of nutrients has led to lush sponge cover, making this the preferred hangout for the local turtles, which can be seen napping atop the coral, making a meal out of the pinnacle itself or ascending to the surface for a quick breath of air. At the surface we’re treated to a view of the surf breaking at the edge of the barrier reef with the neighboring island of Moorea in the distance.

Moorea

As our ferry travels through the coral pass into a glistening aquamarine lagoon, I involuntarily sigh, awestruck by Moorea’s topside beauty. Low clouds hang over the jagged green precipices that arise between Cook and Opunohu bays and then stretch into the distance. It’s no wonder this romantic island, which regularly appears on lists of the world’s most exquisite destinations, attracts countless honeymooners. I’m tempted to forego diving and laze on a hammock all afternoon with a gushy novel, but I reconsider as soon as we begin unpacking our gear while looking out at the spectacular ocean. If it’s this lovely topside, it has to be incredible under the waves.

We find a boat that will take us to the Sandbar, a popular snorkeling site inside the lagoon that we’ve heard can attract crowds. Fortunately, at this hour of the afternoon we’re joined by only a few paddleboarders weaving around the area. After donning our snorkels and hopping in, we’re soon swarmed by friendly stingrays and tiny blacktip sharks accustomed to being fed by visitors on local tour boats. It’s an experience better than any umbrella drink, and it helps to get us amped up for the next morning, when we’ll explore Eden Park (also known as Opunohu Canyons), a lemon shark hotspot.

After arriving the next day, we descend past an eager tangle of blacktip reef sharks at the surface while on our way to photograph the local celebrities. A trio shows up shortly thereafter; two large females and a smaller male pass low over the reef, with their prominent choppers giving them a fearsome appearance that doesn’t quite jibe with their graceful, cautious passes. Nearby Coral Wall (part of the reef that encloses the lagoon) is less sharky but every bit as exciting. We descend through swirls of surgeonfish and barracuda to discover a meandering series of nooks and crannies covered with hard coral. Two Napoleon wrasses show up almost immediately and follow us from a distance throughout our dive, but the highlight is the ample turtle population, with greens and hawksbills slowly passing us every few minutes.

The mellow pace suits us just fine, because we know we’ll soon be headed to Fakarava and Rangiroa, where mellow is simply not an option.

Fakarava

“The lagoon is full,” our divemaster tells us as we motor toward Garuae Pass, the 5,200-foot-wide channel that encompasses North Fakarava’s best-known dive sites. He explains that high surf south of the atoll has been pushing so much water into the lagoon that they’ve not had an incoming tide for days. Outgoing currents have been strong and present on almost every dive.

This atypical condition is bad news. Diving in French Polynesia’s passes, the channels that connect the lagoons to the open ocean, is wholly dependent on tide. Although it’s nearly always possible to dive one of the bordering reefs regardless of the direction of water flow, venturing into the heart of the passes themselves — home to ripping currents, high-octane drift dives and the legendary “walls of sharks” — is done only on incoming tides. Incoming tides bring blue ocean water and extraordinary visibility and allow divers to finish in a safe, calm lagoon rather than in the open ocean.

We have only two days to explore this world-famous atoll, and we’d been hoping against hope (and apparently nature) that the tides would line up well for us. The divemaster sees our dismay and promptly shifts into damage-control mode. “Don’t worry,” he said. “We’ll just stick to the reef. There were mantas and lots of fish there yesterday.”

We drop in at Central Park, descending to the edge of the wall and staring cautiously at the misty cyan water rushing past. Venturing even a few feet over the reef’s edge demonstrates a good reason for trepidation — the downcurrent pulling over the wall is formidable, and the outgoing current is also incredibly powerful. Any diver unfortunate enough to be caught in this kind of flow could be transported either over the wall into the depths or into the open ocean at speeds that would make recovery very challenging. We stick close to the reef, which is well-attended by blacktip, gray reef and even occasional silvertip sharks (though not stacked end-to-end as we’d hoped). Minutes later we spot a graceful pair of mantas taking turns getting touch-ups at a deep cleaning station. We ease our way up the reef, finding not a wall of sharks but certainly walls of fish. Our cameras stay busy as huge schools of surgeonfish swarm over the reef, interrupted only by the occasional cluster of trevally.

On our last day, the swell to the south begins to abate, and at last we’re able to experience a single dive at South Fakarava’s famous Tumakohua Pass. The incoming tide is predicted to be extremely brief, so we hurriedly gear up and hop in. Minutes later, we’re tucked into one of three gravelly crevices that act as viewing galleries. We soon spot a small group of gray reef sharks. Our dive guide had said that swimming into the blue will disrupt the action here, so we resist the temptation to swim toward them and instead stay low and minimize our bubbles. Our discipline is rewarded minutes later. We watch in awe as gray reef sharks, stacked as far as the eye can see, bend gracefully in the azure-tinged water.

Truly, this is what all divers envision when they think of French Polynesia and especially the Tuamotus. Our time ticks down too quickly, and before long we’re in the shallows, surrounded by schools of snapper. Elation swells through me, soon to be replaced by disbelief that we’re able to experience only a single dive at this amazing site. As an eagle ray buzzes past, I adjust my attitude. Now that I know what’s here, I have every reason — and solid plans — to return.

Rangiroa

The tally is dolphins 5, us 0, and I’m feeling down. We’ve spent more than five hours in, around and whizzing with the current through Tiputa Pass, the narrow channel famous for close interactions with a playful pod of bottlenose dolphins. To be more specific, that’s five hours during which we could hear dolphins constantly squeaking and chortling but during which we’ve seen exactly zero dolphins. We’ve seen nearly all the other big-hit Rangiroa marine creatures, such as manta and eagle rays, swarms of gray reef sharks, big schools of snapper and an outlandishly huge (and hugely pregnant) tiger shark, but no dolphins. It’s maddening, and the soundtrack combined with intense wishful thinking is playing tricks on my mind. I stare desperately into the expanse and realize that all kinds of objects are now beginning to resemble dolphins, including surgeonfish, our dive guide and random crud in the water column. The squeaking is deafening, but still no dolphins — and I can’t take this torture anymore.

I shake my head and descend toward the wall, where a large eagle ray is lazily circling. As I start adjusting my camera settings in the hopes of a close pass, I hear a bell ringing insistently — a signal from our dive guide that he finally sees dolphins approaching. I kick as hard as I can until I finally see a group of six (including an adorable baby) swimming unhurriedly but with purpose, checking us out as they continue toward their destination. I manage to capture a few “proof” images, and then I put down my camera, assuming the moment is over.

Minutes later, however, members of the pod make it their business to live up to their reputation: One individual begins to closely follow our dive guide, seemingly pestering him for scratches. Meanwhile, I’m having the underwater moment of a lifetime as the new mother dolphin has also developed an interest in us and begins to inspect me, with her baby carefully hidden behind her. After a few minutes she begins to allow her baby to peep out, and a joyous game of hide-and-seek ensues. I do my best to mimic the baby’s agile movements, turning and flipping clumsily alongside them until they depart, leaving me giggling in their wake.

I continue to stare into the blue long after they’ve disappeared, thinking to myself, “Dolphins 5, us 1.” And an incredible, lifechanging one it is.

How to Dive It

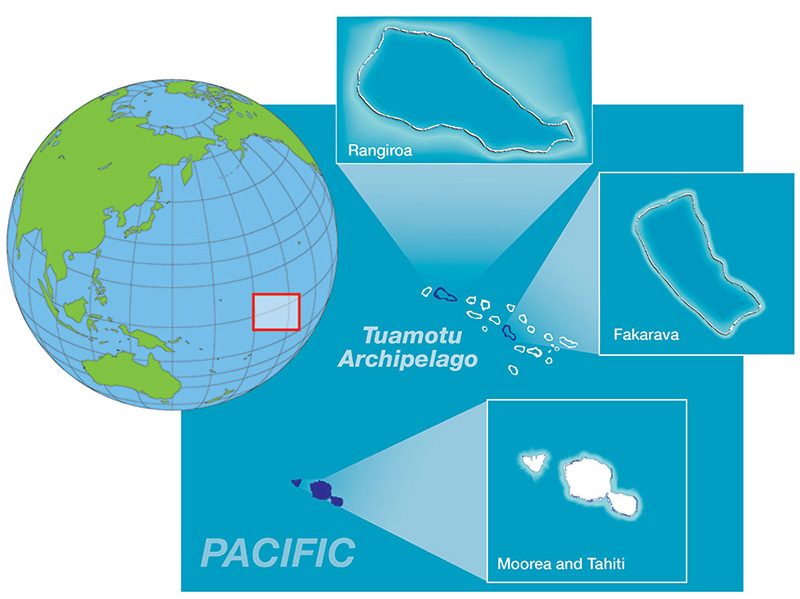

Getting there: French Polynesia is composed of 118 islands divided into five island groups: the Society Islands (which include Tahiti and Moorea), the Tuamotu Archipelago (which includes Fakarava and Rangiroa), the Gambier Islands, the Marquesas Islands and the Austral Islands. The capital is Papeete on Tahiti. Numerous airlines fly directly into Papeete’s Fa’a’āInternational Airport. Air Tahiti offers the best schedule of connecting flights to islands beyond Tahiti. Ferry boats are particularly efficient in connecting Tahiti and Moorea.

Conditions: French Polynesia’s tropical climate offers average daytime temperatures in the low- to mid-80°F range. There are two distinct seasons: Winter (April through October) is cooler and drier, while summer (November through March) is characterized by warmer temperatures with greater humidity and rainfall. Water temperatures are also in the low- to mid-80s year-round. Visibility averages 100 feet, though it may be less during an outgoing tide, especially following periods of high rainfall. It can be substantially greater as well, with 200-foot visibility possible in some areas.

Diving: French Polynesia has several lagoon sites that are ideal for novice divers as well as sites that are “shoulders” (seaward of the cut but distant enough from the point that the current abates). Many of the best-known dive sites, however, are high-current pass dives or deeper, open-ocean sites. Local regulations strictly limit open-water and advanced open-water divers to a maximum of 100 feet. Rescue divers and above are allowed to dive to 131 feet. Deep-diving specialty certifications are not recognized, and most divers find it best to attain an advanced or rescue certification before their French Polynesia adventure. Many operators don’t offer night dives in the Tuamotu Archipelago due to safety reasons and the remote locale. It is critical to pay close attention to dive briefings and stay with your divemaster during pass dives because currents can be extreme. Surface signaling devices are a must. Full 3 mm wetsuits and gloves are recommended for warmth and protection from hard corals, especially during high current situations. A hyperbaric chamber is located in Papeete.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2019