Nature photography, like sports photography, relies on a quick trigger finger to get the story right. After 25 years of photographing fishes for two editions of Reef Fish Behavior: Florida, Caribbean, Bahamas, however, my wife, Anna, and I have found that an educated trigger finger is every bit as important for documenting fish behavior.

Preparing for the right shot often requires hours of observation to determine the critical instant that will best showcase the behavior we’re seeking. How to finesse your way close enough to capture the magical moment is another matter altogether.

Since the publication of the first edition of our book in 1999, fish watching has taken us halfway around the world to record Indo-Pacific marine species for field guides. Each year we invariably made it back to the Caribbean for a month or two to gather additional material for our favorite pet project — the next edition of Reef Fish Behavior.

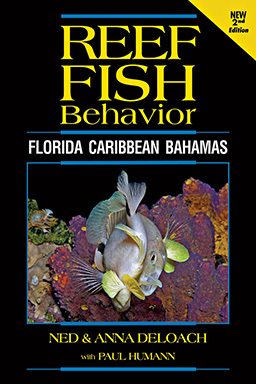

The new edition finally arrived off the press 20 years to the month following publication of the first edition. Compiled from personal observations and pages of research papers and accompanied by a gallery of 588 photographs, the book offers an overview of what is currently known about the lives of reef fishes inhabiting the Caribbean and its neighboring waters. We wrote the content with recreational divers, underwater naturalists, photographers and budding biologists in mind, placing special emphasis on helping photographers find and document seldom-seen underwater imagery.

Beginning underwater photographers initially concentrate on animal portraits and then branch into seascapes before venturing into the realm of behavior photography with its endless challenges and untapped possibilities. In most circumstances, behavior photography doesn’t require sophisticated equipment. Knowledge, patience, tenacity, luck and slow movements are far more critical for success than multiple strobes and long lenses. Today’s small, light-sensitive, point-and-shoot cameras in watertight housings can often produce quality images.

I’m a minimalist and take most of my images with a Nikon D800 with a Micro-Nikkor 60mm lens inside a stripped-down Ikelite housing with a single Ikelite DS160 strobe centered above the lens port. I use manual focus, manual f-stop and low ISO settings, and I tend to keep the power output on my strobe dialed down for rapid-fire situations.

There are two basic approaches for capturing behavior shots: roving around like an opportunistic predator searching for chance encounters or planning dives that target a specific behavior. Falling into the first category, three classic fish behaviors — gaping, yawning and predation — are fleeting and require a quick response.

Gaping occurs when two members of a social group such as a harem face off with their mouths open. The ritualistic confrontations, in which fish compare the size of their open mouths as a proxy for their body size, help establish and maintain hierarchy in groups where size dictates dominance. In instances where the mouth of one rival is wider, even by a hair, the lesser of the two opponents relents, and the provocateurs peacefully go their separate ways.

The key to the shot is noticing the initial face-offs and getting into position before the contest begins. On uncommon occasions when the fish prove equal, the pair resorts to mouth-to-mouth combat. One of the two usually concedes within seconds by rapidly swimming away. At other times adversaries refuse to stop slinging around each other in protracted struggles that can last the better part of an hour — a photographer’s dream.

Many fishes, especially lie-in-wait predators such as frogfishes and scorpionfishes, occasionally stretch open their large mouths so wide you can see their gullets. No one knows the purpose of the impressive yawns. The practice may keep the jaws limber for the fast action required to inhale prey or perhaps serves as a threat reaction. The fact that fishes yawn most frequently as divers approach gives credence to the second hypothesis.

It is preferable to shoot from the front and on the same level as the subject with your strobe aimed directly at the mouth to minimize internal shadows. Most important, will yourself to wait until the last moment when the yawn is at its widest and most spectacular before pulling the trigger. If you fail to get the shot you want, remain in place; about half the time a fish will quickly follow with a second yawn.

Although fish predators (known as piscivores) regularly capture prey, prized images of a fish eating another fish are rare. The difficulty arises from the speed of feeding strikes as well as the piscivores’ preference for small prey that quickly slides down their throats. Luck comes when predators make the mistake of grabbing prey too large to easily swallow or taking a fish tail-first, forcing the predator to swallow against a phalanx of backward-pointing spines. These miscues often lead to prolonged life-and-death struggles, providing ample time to get multiple shots.

If you’re drawn to the dramatic and undaunted by a challenge, photographing the sex life of reef fishes might be of interest. If so, get your trigger finger ready for fish ballets, courtship displays and high-octane spawning rises capped by explosive open-water gamete releases, known as broadcast or pelagic spawning. Dusk is the best time to be underwater to try to capture these behaviors.

Males arrive at traditional spawning sites ready to shed sperm. Females require extra time for their valuable cargo of eggs to hydrate (the absorption of ovarian fluid necessary for eggs to float after release). Courtship often appears to an inexperienced eye as little more than fish milling about the bottom. But after observing a tryst or two, the signs become unmistakable. Watch for color and pattern changes, fin displays, body twitches and more obvious signs such as females, swollen with eggs, hovering above the bottom like blimps as brightly colored males race about chasing off sneaker males (one of my favorite pieces of biological jargon). Species vary in their reactions to divers during reproduction. After courtship begins, nothing seems to bother wrasses, flounders and small sea basses, but daytime-spawning parrotfish are hesitant to spawn with divers around.

Fortunately, courtship typically continues for an hour or longer before the first spawn. The lengthy preludes offer an opportunity to take numerous shots of males displaying and cajoling their hydrating females. Stay alert for spawning rises that send gamete-swollen pairs spiraling toward the surface at unexpected times. If you follow a pair up, there is always the outside chance of capturing a split-second gamete release — a trophy in any portfolio.

Approximately 25 percent of reef fishes lay nests full of eggs that are protected by guardian males. Male yellowhead jawfishes take parental responsibilities to extremes by incubating eggs inside their mouths. These graceful, 3-inch sand-dwellers are quite wary, slipping tail-first into their burrows when approached. Moving in close for a shot can be a drawn-out affair requiring plenty of patience — the currency of the realm in behavior photography. If you can eventually slip in close to one and are willing to commit even more time, the male might aerate his developing offspring by partially blowing out and sucking back in his mouthful of eggs.

Cleaning stations showcase graphic interactions between parasite-plagued fishes and the attending shrimp and small fishes that remove the pests. Images of cleaners picking parasites out of open mouths and from beneath gill covers are classics. Much like with jawfish, cleaning stations also require a lot of time to maneuver close enough for the shot you want. Start by selecting an actively working station with shrimp waving their long antennae and clients arriving regularly. Settle out of the way and study the interplay for a while to get an idea of the best shot available. If clients stay away after you’ve moved closer, back off and try again later or just wait them out. The cleaners need to eat and their clients want relief, so time is on the side of patient divers.

Most photographers have heard about the exotic offshore menagerie of larval fishes and invertebrates that rise near the surface after dark to feed. These tiny, otherworldly life forms supply a wellspring of novel images for underwater photographers to track down in the open ocean. While gathering material for the first edition of Reef Fish Behavior in the mid-1990s in South Bimini, Bahamas, we used hand nets to capture larval fish night-lighted to our boat. We later took them underwater to photograph. Regrettably, we didn’t have the foresight to drift along the edge of the nearby Gulf Stream where sea life proliferates.

One evening after returning to the dock with a bucket full of our little treasures, a Bahamian fisherman told us about seeing young marlin that would fit in his hand. For 25 years the story remained in my imagination until one summer night while drifting off Florida’s West Palm on the opposite side of the Gulf Stream from Bimini, I photographed a half-inch larval marlin, only weeks old, already sporting the bravado of the great animal it would become.

And then there are those rare instances of being in the right place at the right time for improbable images that fall into your lap. Male sergeant majors spend their days chasing away marauding bands of wrasses and other egg pirates from their egg-filled nests. The guardians finally get some rest after sunset, when fish predators bed down. One evening while on a planned dive to photograph hatching sergeant major eggs, I watched a night-prowling clinging crab clamber out of the shadows and begin plucking off the puppy-eyed embryos one after the other with a nutcracker-styled claw — a bittersweet image of reality.

In another opportune incident, luck came my way in the form of baby balloonfish the size of ping-pong balls that hovered in tight-knit groups along the shore of Dominica. So many balloonfish were about that they even gathered beneath the dock at the hotel where our dive boat was moored. I slipped in from shore for a look. Through 10 feet of inshore haze I saw the same tightly packed group, but this time all the fish were facing the same direction. If I were giving out gold stars for cute, these little fellows would be awarded all five. Trying not to disturb the silt or the fish, I pulled myself along the pilings and gingerly balanced on the tips of my fins at the end of the dock where my target group seemed comfortable gathering. But as expected, the fish drifted apart at my arrival. A half hour later they formed again only an arm’s length away but impolitely faced in every direction but mine. At some point well into my second attempt to take the shot the following afternoon, 24 balloonfish eyes peeked at me in unison for an instant — that critical instant was all I needed.

© Alert Diver — Q4 2019