Go where the wild things are

During the pandemic I asked my partner, David Doubilet, a question: “If you had one full year to dive in one country, what country would it be?” I thought he might need some time to consider, given he has spent five decades documenting the sea for National Geographic.

“I don’t have to think about it,” he replied. “I would go to the Philippines.”

We think of the Coral Triangle as a massive marine biodiversity vault anchored by three cornerstone countries: Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines on the northern apex. David and I have spent months exploring PNG and Indonesia. The Philippines was always in front of us on a map, in our conversations at the DEMA Show, and talked about by colleagues. It was rocketing to the top of many conservation organizations’ coral and fish counts. Despite all of that, we were late arrivals.

In 2007 we needed to make an image of a clownfish guarding its eggs for a story going to deadline. On advice from Scott “Gutsy” Tuason, I arranged a Philippines stopover for David to spend two days diving in Anilao. David was skeptical the picture would happen, but on the first dive he captured the image that had eluded him for decades. Welcome to the Philippines.

Fast-forward to 2012, when we were in Antarctica. Our enduring connection to the Philippines began in the polar ice aboard the National Geographic Explorer. An excited senior Filipino crew member came to our door to share that a group from Manila was joining us and asked us with subtle humor to be our best selves. The reason behind this unusual visit eventually surfaced: The entourage was a group of experienced divers who came to see Antarctica but also wanted to invite us to dive the Philippines.

They spread prepared maps on chart tables as we scribbled in notebooks about where, when, and why. We had Anilao for macro, wild Tubbataha, Malapascua’s threshers, and Moalboal’s sardines. There was Bohol, Coron’s World War II wrecks and dugongs, Donsol, Dumaguete, Cagayancillo, Apo Island Marine Sanctuary (not to be confused with Apo Reef Natural Park), and Verde Island Passage, known for its infamous currents and record-shattering fish counts.

We left the ice with a standing invitation to join the group for their annual trip to Tubbataha when our schedule allowed. Two years later, with pending assignments behind us, we got serious about a story pitch and needed someone closer to our time zone to help plan a pathway through this labyrinth of about 7,641 islands. We reached out to Chicago diver and photographer Lynn Funkhouser, who went to the Philippines on a medical mission in 1975 and found a region that completely seduced her. She became a Philippines ocean ambassador by proxy and returned for 45 years in a row.

The Ultimate Wilderness

With our Philippines article proposal accepted under the working title A Coral Nation, we began in Tubbataha Reefs Natural Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The country’s coral crown jewel in the heart of the Sulu Sea protects two remote coral atolls and one reef.

Tubbataha’s North and South Atoll and Jessie Beazley Reef rise in blue water, creating a coral outpost that attracts everything: reef fish, sea turtles, patrolling sharks, mantas, whale sharks, and the country’s vitally important last major sea bird rookery. A team of rangers patrols the isolated park year-round, because it’s a tempting target for illegal fishing.

Finally able to accept their Antarctic invitation, we joined Tet Lara, Marissa Floriendo, Patsy Zobel, Vina Concepcion, and Skeet the golden retriever for their 20th trip to these waters. We dropped in on the popular Black Rock, Malayan Wreck, Shark Airport, Ko-ok, and Washing Machine sites, and we met with the rookery superintendent near Bird Islet to absorb the importance of this shrinking bird population to the Philippine nation.

I could describe each dive site in detail, but it is more useful to share one dive at Delsan on South Atoll. We rolled off and flew across coral meadows as we passed school-bus-sized clouds of jacks. At the drop-off we noticed Tet and Marissa’s lights searching knowingly below us until the beam settled on five large marble rays floating gently above a forest of whip corals. I lingered with the rays as their team moved on. Sensing an incoming presence, I turned to my left to see a determined tiger shark approaching. I raised the camera, the strobes flashed, and the annoyed tiger vanished into blue nothingness.

The deep show over, I rose along the slope and saw that I was on course to meet a whale shark. Out of time and air, I headed for a shallow stop, where I found David focusing on a scattered group of hawksbill turtles. All that activity was during just 90 minutes in Tubbataha.

Anilao

We left Tubbataha and met Lynn Funkhauser and filmmaker Leandro Blanco in Anilao. Batangas province is the birthplace of Philippines diving and a mecca for macro shooters hoping for an endless supply of subjects: octopuses, stargazers, Rhinopias scorpionfish in various colors, anemones, clownfish with eggs in different states of development, and goby-filled bottles. Look into everything because some creature is likely renting the space.

It is ridiculous to try and list what you might find because you could encounter anything, including photographers Gutsy Tuason and Mike Bartick, both recently featured in Alert Diver. That should tell anyone all they need to know about why to go to Anilao.

What Lies Beneath

Put simply, Verde Island Passage is legendary. Its currents and fish counts result in its frequent designation as the center of the world’s marine biodiversity. The passage, a strait between Luzon and Mindoro, is the main shipping approach to Manila and Subic Bay. This is one of David’s favorite places to dive. “The reef does not just vibrate with life,” he said, “it sings like an opera in the sea.”

Blizzards of orange and yellow anthias, flocks of vampire triggerfish, jacks, barracuda, and rivers of convict blennies spill across the reef. Its acronym — VIP — is proper for this priceless coral corridor.

Dumaguete

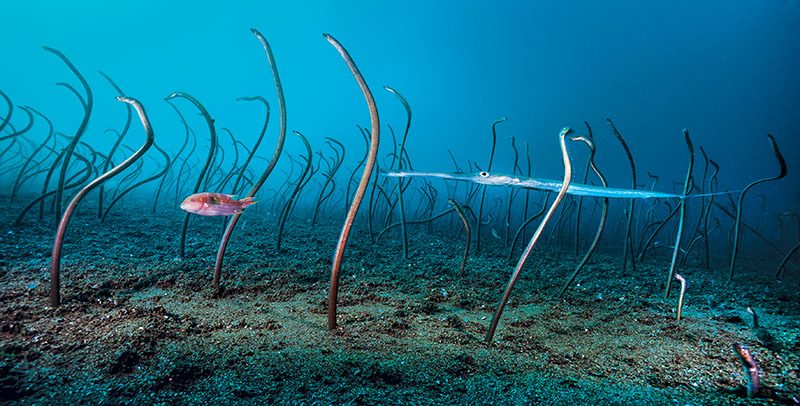

We arrived in the Central Visayas region in the wake of many photographers who faithfully return to explore the sand boulevards, busy house reefs, and nearby Apo Island Marine Sanctuary. David knew about a huge colony of garden eels a short distance from the dive center. These eels are notoriously shy and vanish into their burrow if you cast a side glance their way. A laser-focused David revisited a vintage 1971 technique he developed to make pictures of these creatures in the Red Sea with Eugenie Clark. The Red Sea garden eels image was his first photo published in National Geographic, so photographing this colony felt like a homecoming.

We scouted the colony to select remote camera sites. I located a rock the size of our Seacam housing and left it where we would later place the camera so the eels could acclimate to the intruder in their midst. The next morning we swapped the rock for the housing and ran a trigger cord behind an artificial reef. We left the eels alone while we photographed a sunken boat bulging with striped catfish. When we returned, the colony was standing tall, swaying and feeding on plankton in the current. We watched and waited for unusual moments, and on cue a wrasse swam through the garden, closely followed by a cornetfish. The pair raced through the garden without a single flinch from an eel.

Moalboal, Cebu

Unlike other sardine runs around the world, Moalboal’s sardine shoal, a few kicks from Panagsama Beach, is a year-round phenomenon. Millions of sardines create schools dense enough to obscure the sun unless you have a freediver buddy making shafts of light through the living canopy. While swimming the coral ledge beneath the school, I passed two slumbering sea turtles that I hoped would wake and rise toward the cloud of sardines above, but they did not. I moved on, keeping one eye on the turtles when the other eye noticed a well-camouflaged frogfish the size of my housing lurking in the shadows. I was sizing up a photograph when the apparent rock beside my subject walked away.

Malapascua, Cebu

Malapascua is one place on this planet to somewhat reliably encounter thresher sharks. A thresher dive begins with a 4 a.m. briefing and a dark boat ride to the Monad Shoal cleaning stations. You descend without strobes in the predawn light and wait behind ropes designed to provide the ultra-shy sharks with a comfortable approach to their cleaning station. This is a place to exercise patience — they can appear like ghosts at the edge of your vision, not appear at all, or break off an approach for reasons only they know. A shark encounter is not guaranteed; a solid shark encounter means you saw one, and a great shark encounter may require a few days or just plain luck. Seeing them on their terms and leaving with a few solid frames was rewarding.

A no-shark day is not a wasted one in Malapascua. David and Gutsy spent hours off Chocolate Island filling digital cards with bobtail squid, Rhinopias, mating flamboyant cuttlefish, and snake eels. They spent enough time in the water to annoy a boat captain used to a 60-minute dive. Unfortunately, you’ll sometimes hear an odd, hard-to-describe zapping sound in the background. The noise is from distant bomb fishing. Chances are high that you will stumble across evidence of the illegal practice here and in other locations in the Philippines.

Oslob and Sumilon Island, Cebu

Sumilon Island was the first marine protected area established in the Philippines. There we explored what a typhoon can do to a coral reef. We descended to a nearly empty, toppled reef swept clear by Super Typhoon Haiyan in 2013. Rounding a corner, we finally saw what hope looks like: A single anemone had found its way to the top of a dead coral pillar, and one anemonefish had found its way to the anemone. I stopped and stared at this pair of colonizers, aware that I was seeing a reef on its way back to life.

Oslob, a village across the strait from Sumilon Island, is at the center of a lingering controversy. The village comes to life when locals head to their outriggers, preparing for the hundreds of tourists who will appear at dawn with money to observe, snorkel, or dive with whale sharks. We arrived early by boat and watched the sharks glide in from all directions, timing their arrival with the guests. These magnificent gentle giants come to compete for prime positions beneath outstretched hands filled with krill that attract them like a cat to catnip. The boaters paddle the excited, nervous, screaming tourists in a loop, keeping the sharks and krill handlers at the center of the chaos.

Those who support this style of whale shark tourism maintain that the sharks are ocean ambassadors that inspire awareness of and connection to the sea and provide much-needed income for education, housing, and health. Scientists, nongovernmental organizations, and researchers offer the counterargument that daily provisioning modifies behavior, seasonal migration routes, reproductive strategies, and affects their overall body condition.

For the truly whale shark obsessed diver, other locations in the Philippines offer encounters on the sharks’ terms: Tubbataha (April to June), Donsol (January to May), and Leyte (November to May).

Coron, Busuanga

We wanted to photograph dugongs. They are critically endangered in the Philippines, with their remnant populations scattered and on the brink of local extinction. The largest remaining population is in Palawan province.

Dirk Fahrenbach greeted us on the dock with a hearty hello after a flight, drive, and boat trip. He then broke the news with the dreaded phrase, “You should have been here last week.” David winced when Dirk told us that the visibility had dropped to inches the day before our arrival.

The next morning our bangka motored through calm seas to distant seagrass beds. Dugongs are shy, some more than others; with low to no visibility, our guide, Omar, wanted to locate a friendly one. He stopped the boat in a few places, stared into a sand-colored sea, and finally said, “Just here, straight down.” There was no indication that any air-breathing mammal was within miles, let alone 15 feet below us.

I put on a tank and rolled off, quietly dropping straight down where he said I would see a dugong. The visibility had improved to a whopping 2 feet or so. I was thinking this was a pointless exercise as I sank through a veil of quiet nothing until I heard a faint sound like a trowel working through sand. A dugong eating tiny stalks of seagrass appeared inches beneath my fins, causing me to carefully adjust course. I listened and watched more than I photographed and let the magic of the moment seep into my soul. Thank you, Omar Lingansan; I grew that day.

There was one more surprise. Dirk asked if we wanted to join him to see a recent discovery: a Japanese Nakajima Hayabusa plane — the most intact wreck of its kind — resting in 40 meters (131 feet) of water. We left at sunrise and descended through early dawn light to a rare and unexpected look into World War II.

You Are Needed in the Philippines

The Philippine Commission on Sports Scuba Diving is committed to strengthening and promoting dive tourism. It is working — the Philippines was recognized as Asia’s leading dive destination at the 2022 World Travel Awards for the fourth straight year.

Here is a simple reality that everyone who goes underwater can understand and appreciate: Scientists, conservationists, and divers are fighting to protect what remains of Philippine coral reefs. Reports indicate much has been lost, but Tubbataha’s history is an example of recovery to become a world treasure.

When you dive the Philippines, you are not just a tourist — you are collaborating to bring awareness to some of the most important reefs in the world. We hope to see you there.

Explore More

See more of the Philippines in a bonus photo gallery and in these videos.

© Alert Diver — Q1 2023