The Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site

Sir John Franklin’s expedition in 1845 to search for the Northwest Passage ended in tragedy when HMS Erebus and HMS Terror, with their combined 129 crew members, vanished in the Canadian Arctic, seemingly without a trace.

Evidence of ship desertion collected by search parties, harrowing reports by local Inuit observing signs of cannibalism among the final survivors, and the total disappearance of both vessels gripped the world’s imagination, fueling fascination and speculation about the lost expedition for nearly 170 years. When searchers located the wrecks of the ships in 2014 and 2016, they discovered them to be astonishingly well-preserved and largely intact in the frigid Arctic depths, marking one of the greatest maritime finds in history.

Underwater archaeologists from the Parks Canada Underwater Archeology Team (UAT), who led the search, enter the same unforgiving waters that claimed the Franklin Expedition’s two vessels as they attempt to piece together the mystery of the ships’ disappearance while facing some of the harshest dive conditions on Earth. Over the decade since their discovery, the wrecks have ultimately provided more questions than answers. What has emerged is a growing investigation into two icons of global maritime history and one of the most challenging and complex underwater archaeological projects ever undertaken.

Disappearance and Discovery

European explorers had pursued the dream of linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through a northern sea route since the 16th century. By 1818 England had renewed this ambition to chart the fabled Northwest Passage. Expediting travel between Europe and Asia held the potential for England to solidify its dominance in global maritime trade and expand the reach of its empire.

In May 1845 Capt. Franklin, Capt. Francis Crozier, and Capt. James Fitzjames departed England with the Erebus and Terror. Their now-fabled expedition’s mission was to finish mapping the Arctic coastline and establish a navigable route through what is now the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Both ships were well-provisioned and equipped with the era’s latest technology, including auxiliary steam engines, robust hulls to protect the ships’ integrity against the ice, and sustenance and supplies for at least three years.

When two years passed without contact between the ships and the British Admiralty, public anxieties mounted, and England launched the first search parties to the Arctic to try to locate them. Dozens of ships combed the frozen north over the following decades, first in hopes of rescue and later to recover evidence that would indicate the expedition’s fate.

An 1854 search party shared reports from the Indigenous Inuit of encounters with Franklin Expedition crew members, including disturbing descriptions of cannibalism among the last survivors. The news was distressing, and Britain’s Victorian population received it poorly.

The author Charles Dickens published an article denouncing the Inuit accounts, believing that civilized British naval officers would never resort to such a morally reprehensible act and suggesting instead that the Inuit may have murdered the sailors. His stance was shaped in part by public sentiment, by Lady Jane Franklin’s determination to protect her husband’s reputation, and perhaps even by the fact that Dickens’ works were listed among the books carried aboard the expedition’s shipboard libraries.

Spurred by the continuing drama, the British sent additional search parties, culminating with an 1859 expedition that discovered a single-page document left behind on King William Island. The first part of the message, dated May 1847, stated that the expedition had been trapped in the ice since September 1846. The second entry below it, from nearly a year later, stated that 24 men, including Franklin, had died. The remaining 105 survivors had deserted the ships, which remained trapped in the ice. According to the letter, they left on foot to proceed south to mainland Canada in search of rescue.

Research and land-based archaeology over the past 170 years have confirmed that no survivors made it to their intended destination. The once-vilified Inuit testimony proved to be accurate when archaeological and osteological investigations of discovered Franklin sailors’ skeletal remains confirmed the bodies were mutilated in a manner showing evidence of survival cannibalism. Fitzjames’ lower mandible, for example, exhibited multiple deliberate human cut marks, indicating the desperate situation and that neither rank nor social status mattered in the expedition survivors’ final days.

While the search for the Franklin Expedition helped map the Canadian Arctic, and the Northwest Passage was eventually found and charted, the fate of Erebus and Terror, along with the loss of all 129 men, remained one of history’s greatest maritime mysteries for almost two centuries. The Historic Sites and Monuments Board of Canada preemptively designated both wrecks as a national historic site in 1992 to safeguard their legacies if they were ever found.

Parks Canada’s 60-year-old UAT, working in conjunction with Inuit knowledge holders, modern technology, and other partners led a renewed search for both ships in 2008. Their collective tenacity, dedication, and meticulous search of thousands of square kilometers of treacherous arctic waters yielded the discovery of Erebus in 2014 and Terror in 2016.

Longitudinal Logistics

Unlike warmer waters that are easily accessible and diveable year-round, the only open-water dive season in the frigid Canadian Arctic near King William Island and the Adelaide Peninsula is from mid-August into September. The two dive sites are completely covered in solid ice the rest of the year. During the brief period when the ice cover departs long enough to allow direct surface access to the wrecks below, UAT divers plunge into Arctic Ocean’s waters that hover barely above 32°F (0°C).

Each field season requires six months or more of meticulous planning and preparation; the significant time investment, travel duration, and year-round dedication to the project by each team member equates to mere weeks of underwater time. The window of availability for safe diving in the dynamic conditions at the wreck sites has been as small as 11 days for the UAT’s annual expedition. One year, when the weather was exceptionally agreeable, the team had 23 days before encroaching inclement conditions forced them to depart.

The water conditions at the two dive sites can change rapidly, but the ice conditions around the sites dictate access to the work areas, making it either inaccessible or impossible to leave. Simply getting into a position to step into the water is one of the project’s most challenging aspects. Arrive too early or leave too late and the Parks Canada research vessel RV David Thompson could become trapped in the ice just like the Franklin Expedition’s ships.

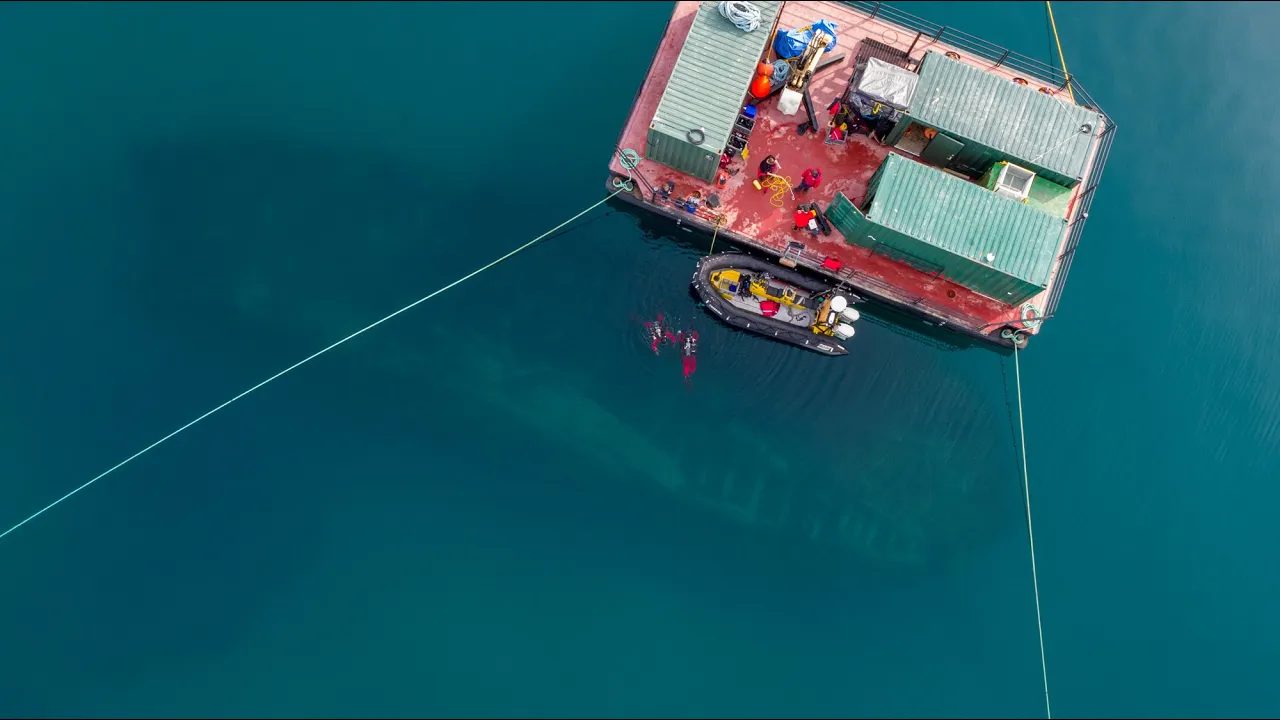

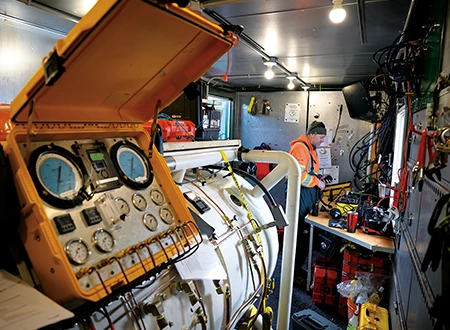

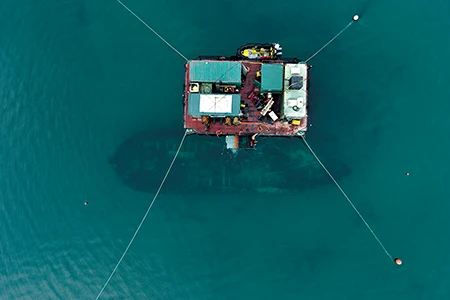

The support barge Qiniqtiryuaq serves as an excavation and dive platform at the Erebus work site. The barge is kept year-round in nearby Gjoa Haven, where it is retrieved and towed to the site by the David Thompson and then moored directly over the wreck for each short season. The Qiniqtiryuaq features a hydraulic crane and an archaeological laboratory where the team can immediately catalog and store recovered artifacts for transport back to the mainland. It also houses the dive operations center, where the topside crew tends to the divers below, and a hyperbaric recompression chamber ready to receive and treat any diver exhibiting symptoms of decompression illness.

The dive barge and the wreck of the Erebus are within swimming distance from land, and the reality of a hungry 1,000-pound (454-kilogram) polar bear climbing aboard in search of a meal in this scarce hunting environment is not impossible. A pair of .30-06 rifles and shotguns loaded for bear defense are safely secured within reach of the crew, adding to the near incredulous intensity of the overall dive environment. Thankfully, the only precarious animal interaction so far has been with two curious and oversized bearded seals, whose persistent presence caused the divers to terminate their dive.

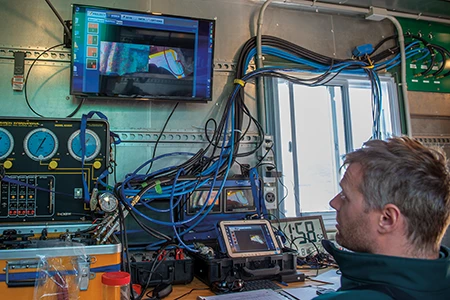

What began as open-circuit scuba dives in thick drysuits and conducted from boats has evolved to resemble a full-fledged, portable commercial dive operation. Hardhat dive helmets and full-face masks with surface-supplied air, communication lines, and hot water pumped into the dive suits for insulation enable the UAT to conduct multihour dives in freezing temperatures.

Dive operations are a constant game of checking the weather, weighing it against the planned objectives for the day, and factoring in what the team accomplished the day prior. With such a short amount of time available on-site, every minute underwater is precious and a delicate balance of safety and efficiency.

Despite the ticking clock until weather forcibly closes the operational window, the UAT conducts missions in a highly controlled and careful manner, adhering to unwavering professional standards and not letting environmental pressures affect their work ethic. The team’s cohesion and continuity of experience play a significant role in their success. Most of the UAT members working on these wrecks have been involved since the initial discovery, resulting in a collective knowledge of the area that continues to grow. This legacy enables a productivity level that could not be replicated by a new team of divers coming in each year.

Excavating Erebus

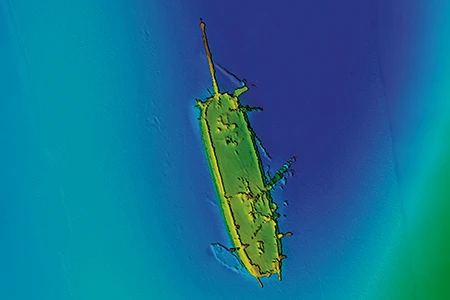

The UAT identified Erebus about a month after they first located the wreck, based on a comparison of the ship’s plans with the wreck’s dimensions. On their first set of dives, the team found the ship’s bell resting on the deck. Although the bell bore no name, its clearly legible date of 1845 in conjunction with the Broad Arrow mark delineated it as one of the Franklin Expedition’s vessels. Documenting the Erebus site became their first mission, and they began excavation planning soon after.

Excavating Erebus has remained the team’s primary focus, as the ship’s depth of only 36 feet (11 meters) and exposure to strong winds and waves has led to significant site deterioration in the past decade. A portion of the upper deck has collapsed, hampering access to the wreck’s artifact-laden compartments.

Efforts to recover an officer’s sextant are a good illustration of the dynamic site conditions. It was observed on one of the first penetrations into the wreck, but it disappeared for several years before the team rediscovered it buried under silt and a piece of shifted timber approximately 1 foot (0.3 m) from its original location.

Artifacts recovered from the Erebus range from everyday items such as a shoe, storage jars, and a pair of eyeglasses to extraordinary discoveries, including fossil specimens that members of the Franklin Expedition collected. UAT archaeologists are now studying not only the wreck as a site but also the findings that fascinated explorers aboard the Erebus generations ago.

A hairbrush excavated from the wreck had 20 human scalp hairs and one facial hair still attached to its bristles, which represents a significant step forward in the study of the Franklin Expedition. The recovery of human hair from such a well-preserved 19th-century shipwreck offers archaeologists a unique opportunity to deepen their understanding of the expedition’s crew, their health, and the conditions they faced.

These and other discoveries often raise more questions than provide answers. The team, for example, recently found 20 pistols in a seaman’s chest inside the Erebus. An individual would have typically used a chest of this kind for storing personal items and belongings. The large quantity of pistols suggests they belonged to more than a single person, however, raising the question about why they were stored together.

Fourteen members of the crew were Royal Marines, who were on board to enforce discipline and be part of the crew’s defensive force. They were not sailors but were equipped similarly to British Army soldiers, so the odd discovery could indicate simple armory storage. The chest also invites speculation about the pistols as a control measure against rising tensions and the potential for mutiny as the ship remained trapped in the ice.

Another possibility is that the chest was simply an abandoned collection point where Inuit salvagers who boarded the ship left the weapons as they tried to recover as many usable items as possible before it sank.

As careful review of artifacts recovered from the Erebus continues, each discovery holds the promise of shedding more light on the lives and ultimate fate of Franklin’s lost crew.

Tantalizing Terror

Discovered two years after the Erebus and about 43 miles (70 km) north of it, the Terror rests in deeper water at nearly 80 feet (24 m), coincidentally found in its namesake bay. The ship is an astonishingly well-preserved time capsule, with the considerably deep, cold, and relatively calm waters of Terror Bay keeping it largely undisturbed. Exterior surveys show the ship’s deck wheel still standing and its bowsprit in place, with some exterior windows still featuring intact double panes.

Remotely operated vehicles that the UAT divers have guided into the Terror’s interior have returned haunting images of the ship’s communal living space near the bow. There are intact shelves laden with food storage and artifacts, a pair of rusted rifles hanging on the wall in the crew living quarters, and the seemingly undisturbed captain’s cabin.

The captain’s giant desk, with its closed drawers preserved in the cold water and sediment, ominously beckons with curiosity about what expedition data might be preserved inside. The chance of finding written documents is real, and it is a future possibility that the UAT could recover them.

One of the mysteries the UAT aims to solve is how the Terror ended up oddly positioned inside King William Island’s southwesternmost bay. The note the Franklin Expedition left behind declared the northwest shore as the site of both ships’ abandonment.

Ice climatology studies conducted with the Canadian Ice Service suggest the abandoned vessels could have drifted south from the known desertion point, carried by the well-documented flow of multiyear surface ice in the region. It is also possible that some crew members were on board one or both of the ships, and could have influenced their movements. While the Erebus continued in a roughly straightforward trajectory before landing in the shallows of the Adelaide Peninsula below King William Island, the prevailing explanation for the Terror is that it was caught in an eddy and swirled back against the ice flow, finally coming to rest in its bay.

While the clock is ticking on the Erebus, the Terror remains safely tucked away, patiently awaiting its turn at excavation and the unveiling of its secrets and questions to the world.

Invaluable Inuit Knowledge

The discovery of Erebus and Terror would not have been possible without the support, advice, and knowledge that the Inuit people of Nunavut so generously shared. Their historical testimonies and personal anecdotes led the UAT in the direction of both wreck sites.

The traditional knowledge passed down through generations has now come full circle almost 170 years after the Inuit first observed the Franklin Expedition’s disastrous and tragic outcome. The discovery of the ships and terrestrial remains have validated over a century of Inuit knowledge and oral histories.

Parks Canada and the Nattilik Heritage Society in Gjoa Haven (Uqsuqtuuq), Nunavut, comanage the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site. Inuit leadership plays a central role in stewardship, including the Wrecks Guardian Program, which directly involves the Inuit people in protecting and monitoring the wreck sites and contributes to further integrating Inuit knowledge into site operations.

Active site surveillance and ongoing terrestrial and underwater archaeological research are joint efforts between Parks Canada, the Government of Nunavut, Inuit organizations, and community guardians. This collaboration ensures the long-term protection of the wrecks and the sharing of Inuit and Canadian heritage. Co-owned by Parks Canada and the Inuit Heritage Trust, artifacts recovered from the Franklin Expedition are studied and conserved in Ottawa before many are returned for exhibition display in Nunavut.

In the summer of 2025, the Nattilik Heritage Centre in Gjoa Haven opened a significant expansion that doubled its size, adding 5,382 square feet (500 square meters) of new exhibition and community space. The new wing displays recovered artifacts from the Erebus, and the exhibits are organized around three themes: the Franklin Expedition, Arctic life during Franklin’s era, and the intertwined histories of the Inuit and Europeans.

With Parks Canada and UAT continuing research to uncover new secrets from both wrecks — and a museum and visitor center welcoming travelers — the Wrecks of HMS Erebus and HMS Terror National Historic Site remains a living project that divers and shipwreck enthusiasts alike can follow for many years to come.

Explore More

Find more about Trapped in Ice in this bonus video.

© Alert Diver – Q4 2025