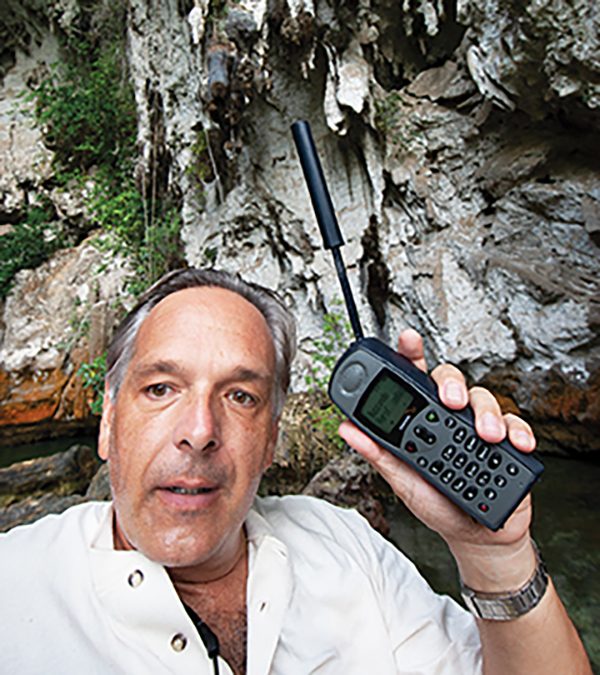

DAN EMERGENCY SERVICES RECEIVED A CALL via satellite phone from a liveaboard anchored off a remote island in the Galápagos. A DAN member was concerned about their bunkmate exhibiting symptoms following the day’s dive activities. The diver had completed four dives that day. Although she began to show symptoms following the second dive, the inexperienced diver wrote off her symptoms, did not seek help, and continued diving.

There were no significant events on any of the simple, recreational dives, but there was a current on the surface, and the diver assumed her shoulder pain was from the exertion required to get back to the boat. The diver denied shortness of breath, breath holds, and buoyancy or equalization issues.

Her dive buddy was the divemaster, who told her on the fourth dive to surface without completing the decompression obligation on the diver’s computer. According to information provided to DAN, the divemaster’s computer had different decompression obligations.

The diver had a total of 40 lifetime dives and was completing an advanced open-water certification. She was using rented equipment and was not familiar with the dive computer.

When DAN medics received the call, the diver complained of pain under her left breast and in her left shoulder, numbness in her right leg, a brief loss of consciousness, nausea, and cutis marmorata (skin marbling) on her abdomen, back, and legs. Both the diver and the crew, however, seemed unconcerned.

DAN medics quickly realized that the situation might be dire. The symptoms and time frame fit the profile for suspected decompression sickness (DCS). The symptoms, coupled with the missed 18-minute decompression obligation, meant that the situation was serious and needed a quick response.

Whether DCS results from a missed decompression obligation or happens despite following correct protocols, having an emergency action plan is a necessary safety preparation.

DAN recommended that the crew immediately activate their emergency action plan (EAP) and get the diver to definitive care. They started surface-level oxygen, but the vessel’s remote location meant they were roughly 18 to 20 hours from the closest medical facility.

A speedboat was dispatched from the mainland to rendezvous with the vessel while en route, but the speedboat’s trip out would still take five hours, with another five hours to return to port and make the transfer to local emergency services.

While rescue operations were underway, the diver’s condition continued to deteriorate. Her symptoms worsened, and she was in and out of consciousness. When conscious, she was in severe pain. The diver was numb in both legs and unable to urinate. Her vision became severely affected. With time becoming an increasingly important factor, the Ecuadorian Navy dispatched a helicopter to expedite the trip.

DAN medics were in contact with the receiving physician, and the diver arrived at the facility in bad shape. She was disoriented, in hypovolemic shock, and had skin lesions and signs of spinal cord and brain injury. Luckily, she gradually improved with treatment.

Divers should have a personal EAP and ensure the operation they dive with has one and the resources to enact it. dan.diverelearning.com

Her dive profiles for the day were the following:

- 81 feet, 54 minutes, 30 percent enriched air nitrox (EAN), safety stop completed, surface interval of 1.5 hours

- 87 feet, 50 minutes, 30 percent EAN, safety stop completed, surface interval of 1.5 hours

- 89 feet, 54 minutes, 30 percent EAN, safety stop completed, surface interval of 1.5 hours

- 78 feet, 57 minutes, 30 percent EAN, safety stop completed, 18-minute decompression obligation not completed

Some divers may erroneously consider these normal recreational dives, but these profiles are aggressive. Four dives in one day are a lot for anyone, and these dives are deep. Not completing decompression contributed to this serious DCS event.

Following your dive computer’s recommendation doesn’t mean that you are safe and that any DCS while diving within parameters is undeserved. A dive computer is only a guide, not a wonder device that can measure inert gas loading in an individual. We are all physiologically different, and many factors contribute to DCS. Your dive computer can only try to quantify inert gas loading based on theoretical science. What works for some individuals does not work for others, and there is a risk every time we get in the water. In this case, the diver also ignored DCS symptoms after her second dive and did not follow the dive computer’s recommended decompression.

There are many takeaways from this incident. For starters, never write off symptoms that manifest after diving. If you dive with a computer, follow its recommendations and warnings. Know the difference between no decompression limit (NDL) and decompression diving, and don’t miss your decompression obligation.

Inert gas loading occurs because of depth and time. The longer we spend at depth, the more inert gas we accumulate. While a dive computer is a useful tracking tool, it doesn’t know anything about your overall health, the dive conditions, or any other factors that affect decompression stress. The closer you get to the NDL, the more inert gas builds up in your tissues, and that increased exposure also increases your DCS risk. More conservative dive planning is the only way to mitigate that risk.

If you are renting a dive computer or are unfamiliar with the one you are using, do your research. Many user manuals are available online from the manufacturer. Read the manual and know how to use your computer, as you should with all your dive equipment. If you have any questions, make sure you get the answers before diving. Never rely on your friend’s dive computer. Each diver should follow their own computer.

A comprehensive refresher course can help you better understand the importance of decompression and how the dive computer plays an essential role in determining your critical safety stops. It’s important to know the basics of recognizing and treating DCS, particularly before diving aggressively in a remote location with little or no medical support. Whether a lack of knowledge or other factors contributed to this diver’s denial, ignoring symptoms can turn a mild injury that is easy to manage onsite into a severe episode that requires an emergency response and can result in paralysis or death. That kind of situation impacts the diver, everyone on the dive boat, and everyone involved in a potentially hazardous, remote rescue.

Always know what you are getting yourself into, especially with a favorite but remote dive destination. What sort of EAPs does your dive operator have in place? Do they have enough resources on board? Do you know how long a rescue operation would take? What is the plan in case a rescue becomes necessary? What is the difference between rescue and evacuation, and when do those actions occur? These are all things to consider before diving, and it is the diver’s responsibility to know this information as part of their personal EAP.

Is your EAP ready to go? Learn how to prepare your EAP with DAN’s free E-Learning course at DAN.diverelearning.com/?courseNo=488. AD

© Alert Diver — Q3 2022