Inner-ear barotrauma is damage to the inner ear due to pressure differences, usually caused by incomplete or forceful equalization. A leak of inner-ear fluid (perilymph fistula) may or may not occur.

Anatomy and Functions of the Ear

The human ear has three distinct sections:

- External Ear

This includes the ear itself and the ear canal to the eardrum. - Middle Ear

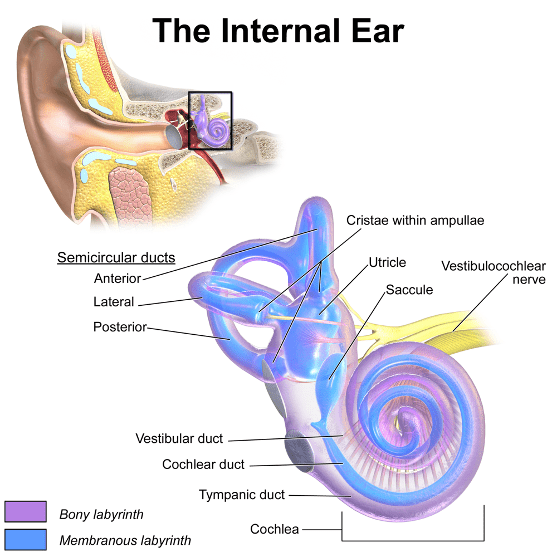

This is an air-filled cavity between the eardrum and the inner ear. It has three components: the middle-ear cavity, the three ear bones (ossicles) and the mastoid process. - Inner Ear

The inner ear is a sensory organ. It is part of the central nervous system, and it has two functions:- Auditory: The cochlea turns soundwaves into electrical impulses for the brain.

- Balance, orientation and acceleration: The canals provide some of our control of balance and position and help detect acceleration.

Mechanisms of Injury

When you properly equalize the pressure in your middle ear, your risk of inner-ear barotrauma is very low. If you do not equalize the pressure in the middle ear during descent, so the water pressure on the eardrum transfers inward and may damage sensitive inner-ear structures. If the pressure is excessive, the oval window or, more commonly, the round window may tear, and the inner-ear fluid may leak into the middle ear. This is known as a perilymph fistula.

The Valsalva maneuver is a common equalization technique. This maneuver increases the intrathoracic pressure, which means the pressure is exerted on all intrathoracic organs. Pliable blood vessels such as the superior vena cava transmit this increased pressure into the head. The skull is a rigid structure with no capacity to expand, so the result is an increase in intracranial pressure. The cochlea is a fluid-filled organ surrounded by soft tissues as well as bone; its only weak point is the external wall in the vestibule, which is adjacent to the middle-ear space. The round and oval windows are two thin and delicate tissues that reverberate with sound. As the increased pressure transmits through the cochlear fluid, it causes an outward movement of the round window.

Pressure waves alone can cause damage to the inner ear without window rupture. If a rupture occurs, the loss of fluid from the inner ear leads to damage to the vestibular system, causing sudden hearing loss and often acute vertigo with loss of balance. If the leak is not stopped soon by spontaneous healing or surgical repair, permanent hearing loss may occur.

Manifestations

Symptom onset is usually sudden and often associated with ear equalization issues. Symptoms of middle-ear barotrauma are often present, but their absence does not rule out inner-ear barotrauma. Vertigo is usually severe and accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Hearing loss can be complete, instant and permanent. Hearing loss in divers usually manifests as loss of higher frequencies (acute, high-pitched sounds). The loss might become noticeable only after a few hours. Divers may not be aware of the loss until they have a hearing test.

Signs and Symptoms

- Ear pain may or may not be present.

- A severe onset of vertigo (spinning sensation) is usually present.

- Loss of spatial orientation is possible.

- Hearing loss, sometimes with tinnitus (ringing in the ears), may occur.

- The eyes might show nystagmus (involuntary rapid and repetitive eye movement).

- A feeling of fullness in the ears (often the least of the diver’s complaints) is possible.

Prevention

- Do not dive when congested.

- Refrain from diving when feeling popping or crackling in your ears, or if you have a feeling of fullness in your ears after diving.

- Learn and use proper equalization techniques.

First Aid

- If you have symptoms of inner-ear barotrauma, do not try to equalize your ears (even if you feel fullness in them, which is likely). This might make things worse.

- Use a nasal decongestant spray or drops. This might reduce the swelling of the mucous membranes, which may help to open the Eustachian tubes and drain the fluid from the middle ear.

- Do not put any drops in your ear canal. If the tympanic membrane is intact, the drops will do nothing. If the tympanic membrane is ruptured, drops might make things worse.

- Lying down and closing your eyes may help with vertigo, which might be significant and will likely make you feel miserable. Try to remain calm. Vertigo is usually accompanied by nausea and vomiting.

- First aid providers should administer oxygen.

- Seek professional medical evaluation ASAP. Any doctor should be able to help, regardless of any dive medicine knowledge or training.

- First aid providers should conduct a complete neurological exam and note any deficits. It is important to differentiate inner-ear barotrauma from inner-ear decompression sickness if possible.

- An ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist (otolaryngologist) might be the most qualified physician to help in this situation.

Implications in Diving

For the Diver

- Follow the first aid recommendations above.

- Avoid rapid head movements.

- Avoid any exertion, middle-ear equalization, diving, altitude exposure, sneezing and nose-blowing.

- Do not lift heavy weights; Valsalva-like maneuvers might exacerbate vertigo.

- Lie down and rest. Keep movement and physical activity to a minimum.

- Vertigo might be accompanied by nausea and vomiting. Lie on your side to avoid aspirating vomit.

- It may take time to return to diving, and you should resume diving only after proper evaluation from a physician with experience in diving medicine, usually in consultation with an ENT specialist.

- Do not neglect these injuries. Some possible complications may have a negative impact on normal living.

For the Dive Operator

- Provide first aid treatment, as described above. As the expedition’s leader, you have a duty of care for a diver injured during your trip.

- Be skeptical of folkloric first aid treatments. Use common sense, and don’t attempt magic solutions. Remember that you might be liable.

- Have the diver sit down, and reassure them during the process.

- Help them deal with vertigo, which can be a very uncomfortable feeling that will likely make the diver — and you — feel uneasy about the situation. Rapid movements of the head and Valsalva-like maneuvers (such as lifting heavy things) might exacerbate vertigo. People with vertigo usually have:

- A spinning sensation: They feel they are spinning or that the environment is spinning around them.

- Repetitive nystagmus: Involuntary eye movement that can occur from side to side, up and down, or in a circular motion.

- Nausea and vomiting: Make sure the diver does not aspirate vomit.

- Have the diver evaluated by a medical professional in a timely fashion.

- Don’t worry about finding a doctor with dive medicine experience. An ENT specialist would be ideal, but any doctor should be able to help with the initial evaluation.

For the Physician

- Assess for middle-ear barotrauma.

- Differentiate between IEBT and IEDCS.

- Assess vestibular function.

- Vertigo, nystagmus and/or hearing loss might be suggestive of IEBT.

- Assess the eighth cranial nerve.

- Strongly discourage your patient from continuing to dive until evaluated by a specialist.

- Consider conservative treatment, including bed rest in a sitting position and avoiding any straining that nay increase intracranial or middle-ear pressure.

- Discourage physical exertion, including lifting heavy things.

- Valsalva-like maneuvers might induce more vertigo if a perilymphatic fistula is present.

IEBT or Inner-Ear Decompression Sickness (IEDCS)?

It is important to distinguish between these two conditions because their treatments differ. The standard treatment for DCS of any kind is hyperbaric oxygen therapy in a recompression chamber. Recompression (or any pressure change) is contraindicated when inner-ear barotrauma is likely. Differential diagnosis between IEDCS and IEBT can sometimes be a challenge. While the symptoms are similar in both conditions, there are a few characteristics that might help during the assessment.

IEBT

- Often preceded by failed equalization of middle-ear pressure

- Usually very acute symptom onset (immediate to a few minutes)

- Usually at the beginning of a dive (during descent) as a result of difficulty equalizing

- Evidence of middle-ear barotrauma — check the tympanic membranes

IEDCS

- Often more delayed symptom onset (many minutes to a few hours)

- Usually the result of a failed decompression after a moderate to significant dive exposure

- Can be associated with a patent foramen ovale (PFO)

- Other forms of DCS, including cutaneous DCS, may be observed

Fitness to Dive

Do not dive until the injury is healed, and you can adequately equalize, preferably under otoscopic evaluation. Assess why the problem occurred (lack of training, allergy, etc.) and address each factor. If you are unable to equalize, then you may consider ENT consultation. The inability to equalize properly is disqualifying.

Note: Do not dive with earplugs, as this may cause external-ear barotrauma.