WATER-RELATED INJURIES

Beachgoing

Despite their often pristine look, beaches can harbor several health hazards — especially those that are popular, in densely populated areas or in developing countries. Walking barefoot on a beach, for example, may expose you to injuries from washed-ashore debris, needles used by drug addicts, pet waste, and parasitic, bacterial or viral infections.

Swimming

Swimming may present other hazards. Water pollution typically increases after big rains due to sewage backups and spills into coastal waters, leading to increased concentrations of disease-causing bacteria that may be swallowed with seawater. Many viruses, bacteria and other microbes can survive for some time in seawater, so avoid swimming after a big rain. There’s no guarantee that clear-looking water is sanitary, but the risks are more significant if the water looks murky.

The spectrum of possible swimming diseases includes hepatitis, diarrhea, Legionnaire’s disease, swimmer’s ear, Vibrio vulnificus, conjunctivitis and even methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Soft-tissue infections with Vibrio vulnificus are also possible and can be fatal in certain cases.

If you plan to spend time at a beach, especially if you plan to swim, visit the CDC’s Healthy Swimming website at cdc.gov/healthywater/swimming to learn about the germs where we swim, how these germs could make us sick and how to protect yourself and others. The website also provides the following information:

- Health benefits of water-based exercise: Did you know swimming can improve your health — and your mood?

- How to swim healthy: Learn how to protect yourself and others before getting in the water.

- Recreational water illnesses: Did you know chlorine and other disinfectants don’t instantly kill all germs?

- Drowning, injury and sun protection: Understand how to avoid injuries.

- Oceans, lakes and rivers: Learn how to stay healthy when visiting natural bodies of water.

Marine Animal Injuries

The sea is filled with creatures that may appear harmless, but some are capable of wounding, poisoning or even killing an unlucky swimmer or diver. Despite the extreme rarity of serious shark attacks, the shark is the most well-known of marine perils. Far more common but less well-known are tiny animals armed with both defensive and offensive weapons that are potent enough to cause human injury. The best protection against such injuries is a healthy respect for these animals. When in doubt, keep your distance.

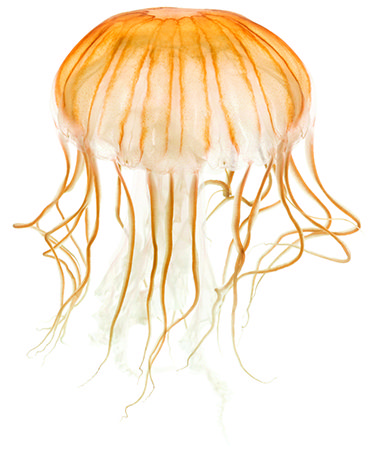

Most marine animal injuries are the result of a chance encounter (such as swimming inadvertently into a jellyfish) or a defensive maneuver by the animal (such as a stingray wound). Injuries are rarely due to aggressive action on the animal’s part. Marine animals are generally harmless unless they’re either deliberately or accidentally threatened or disturbed. When wounds occur, they share many common characteristics despite differing in type and severity. Such wounds are nearly always contaminated with bacteria, frequently with foreign bodies and occasionally with venom.

Swimmers and divers who are concerned about marine animal injuries can lessen their risk of an adverse encounter by showing respect for the undersea environment and knowing the damage that humans can do — and have done — to living marine organisms. Most divers are now aware of these issues and use personal diving techniques that respect the sea and its living creatures. “Look but don’t touch” is the most conservative and considerate approach.

If a marine animal injury occurs, identification of the animal responsible is helpful. Symptoms may not appear until hours after the contact, however, or you may not have seen or recognized the animal at the time of the injury. As a result, treatment must frequently be based on the presentation of the injury, and careful examination of the wound’s characteristics may indicate the most likely cause.

Avoiding contact with marine animals is key, which sounds simple, but it may be more difficult if you have poor buoyancy control or visibility or are in a confined area, experiencing currents or coping with other environmental limitations. The following tips can help you minimize the chance of a hazardous marine life encounter or simply one that might damage the environment:

- Do not attempt to handle, tease, feed or annoy any marine animal.

- Do not explore a crevice with your hand; a concealed animal might try to defend itself.

- Strive to develop excellent buoyancy control, and remain aware of your surroundings.

- Do not allow a current to force you against a fixed object; it may be covered with marine animals.

- Wear protective clothing.

- Research animals you may encounter and learn about their characteristics and habitats before beginning the dive.

Several publications cover in detail both the identification of marine life that can be hazardous to divers and the management of injuries that may follow encounters with such animals. For more information, see DAN.org/Health/Hazardous-Marine-Life. The ability to recognize and identify animals commonly encountered at a chosen dive site will add to the pleasure of a dive and help divers avoid animals that could inflict harm. Some useful guides include the following:

- A Medical Guide to Hazardous Marine Life, 3rd ed. Auerbach PS. Best Publishing, 1997.

- Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine, 7th ed. Auerbach PS. Elsevier, 2017.

- Dangerous Marine Creatures. Edmonds C. Best Publishing, 1995.

- Marine Animal Injuries. Edmonds C. in Bove and Davis’ Diving Medicine, 4th ed. Bove AA, Davis J, eds. Saunders, 2004; pp. 287-318.

- Medicine for the Outdoors, 6th ed. Auerbach PS. Saunders, 2015.

- Pisces Guide to Venomous and Toxic Marine Life of the World. Cunningham P, Goetz P. Pisces Books, 1996.

Japanese Sea Nettle

The venom of the Blue-Ringed octopus can kill adult human being, so care must be taken great fully when handling or seeing this animal.

Sea snake (poisonous) crawling along the ocean shore

DAN Customer Service

Mon–Fri, 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. ET

+1 (919) 684-2948

+1 (800) 446-2671

Fax: +1 (919) 490-6630

24/7 Emergency Hotline

In event of a dive accident or injury, call local EMS first, then call DAN.

24/7 Emergency Hotline:

+1 (919) 684-9111

(Collect calls accepted)

DAN must arrange transportation for covered emergency medical evacuation fees to be paid.

Medical Information Line

Get answers to your nonemergency health and diving questions.

Mon–Fri, 8:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. ET

+1 (919) 684-2948, Option 4

Online: Ask A Medic

(Allow 24-48 hours for a response.)